I’ve always loved handmade things. Whenever you encounter a hand-crafted object, whether it’s an antique watch or a stoneware mug, you are meeting something that is by definition unique. That’s because every such item is the product of a particular moment in time, when a human being put something into the world that can’t exist anywhere else. To hold it in your hands is to converse with its maker.

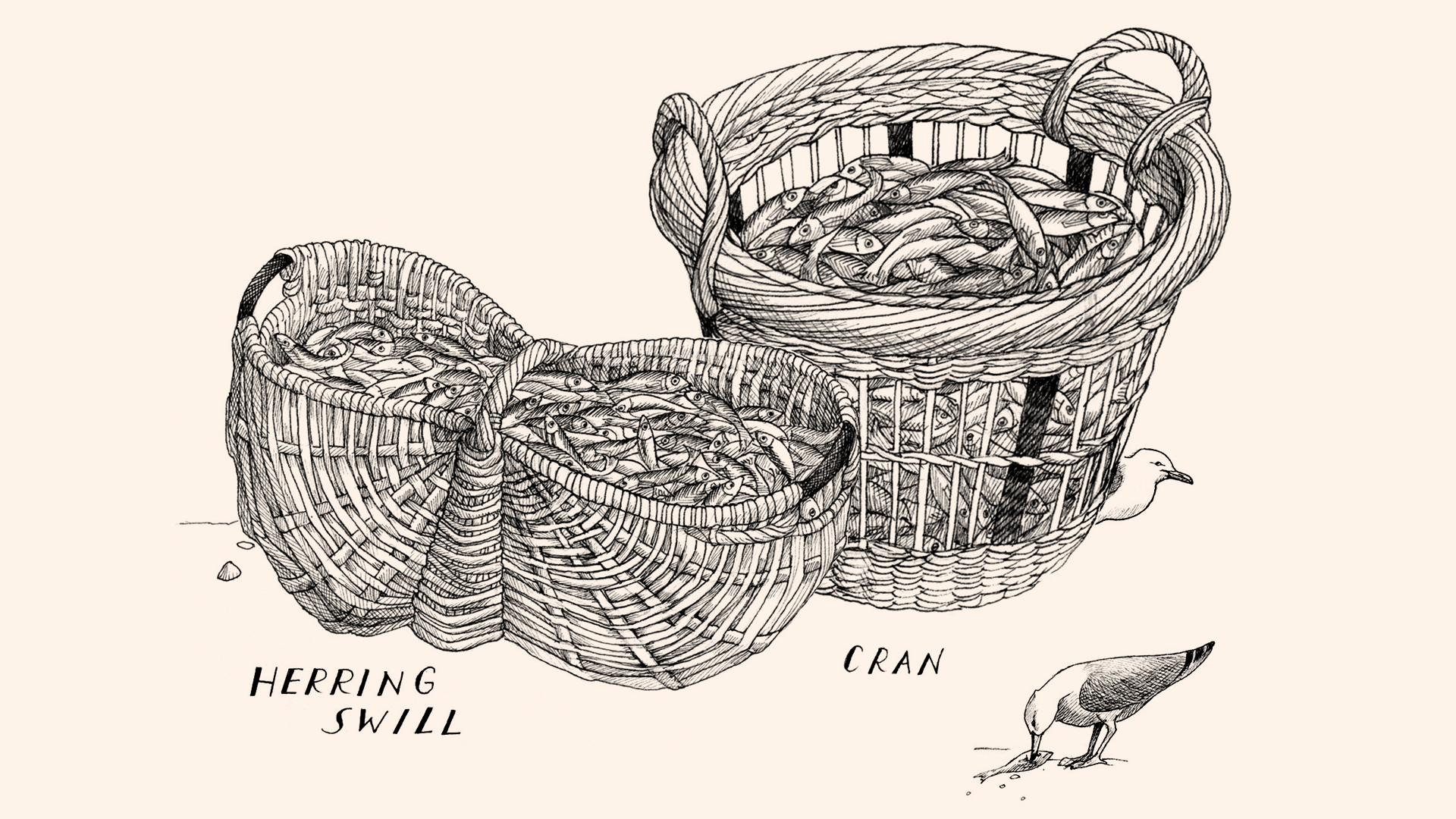

A few hundred years ago, everything in Britain was made by hand. Before industrialisation, craft was an engine of social and economic life. The sound of wheelwrights’ mallets echoed around every high street while smoke from blacksmiths’ forges drifted over every village green. Even the smallest communities had their own network of masons, tailors, coopers, weavers and bootmakers – each using local materials to produce goods for their neighbours.

But over the last century or so the ‘workshop of the world’ has lost the majority of its workshops. As Britain transitioned from a producer society to a consumer society we shed thousands of manufacturing occupations, many of which had been practised on these shores for centuries.

Spare a thought for the ballers, benders, blubbermen, bogeymen, boners, bottom-stainers, cock-makers, devils, eye-punchers, pom-pom men, quarrel-pickers, whiff-makers and willy-men whose once essential livelihoods now sound like vulgar nicknames.

Get the latest news and insight into how the Big Issue magazine is made by signing up for the Inside Big Issue newsletter

As we hurtle into another industrial revolution, this time driven by tech and AI, more jobs will surely go. That’s why I chose to write my new book, Craftland, now. I couldn’t think of a better time to look back at older ways of working and making – partly to chronicle them before they potentially vanish, and partly to see what we might be able to learn from them.