Here is a basic fact: 70% of the earth’s surface is covered by ocean. Every school kid knows this, and we’ve all seen photos of our blue orb floating in the black void of space. Clearly the ocean is immense, yet it’s hard for people to grasp the scope of its immensity. I like to frame its dimensions differently.

Rather than visualising its surface area, think of the globe as a biosphere – a three-dimensional living space. Measured that way, by volume, 98% of it is ocean. And here’s the kicker: 95% of this saltwater realm comprises depths below 600ft, extending down to nearly 36,000ft. Yes, we live on an ocean planet. But it’s more accurate to say that we live on a deep ocean planet.

Get the latest news and insight into how the Big Issue magazine is made by signing up for the Inside Big Issue newsletter

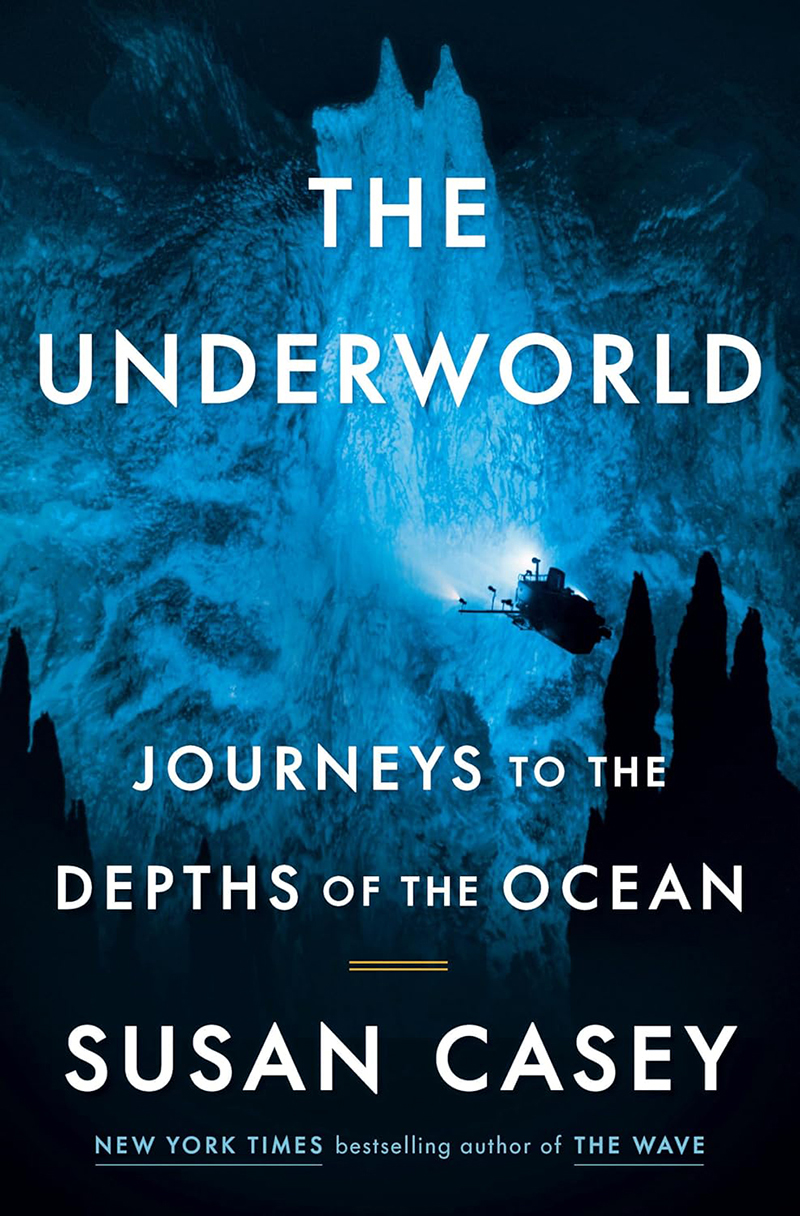

For as long as I can remember I’ve been obsessed by the deep, captivated by the idea of its fantastical landscapes (which we’ve never seen), bizarre creatures (that we’ve never met), lost chapters of history (stuff we couldn’t even guess at), and countless undiscovered treasures (including an estimated three million unknown shipwrecks). There’s a parallel universe beneath the ocean’s surface – a mysterious underworld. Yet we’ve barely explored it. Only rarely do we pay any attention to it.

For a host of reasons, that’s now beginning to change. The deep is the engine that drives the earth’s climate, ocean circulation, heat distribution, nutrient cycling, and geochemistry – among myriad other intricately interconnected systems – all of which make it possible for us to live up here on our 2% patch.

Global warming means that we’re now in a race for knowledge about the ocean before its changes overwhelm us; a race to explore the deep before it’s exploited beyond recognition. A race to protect the biosphere’s silent majority, and ourselves, as the clock ticks loudly. Not that any of this is easy. Everything about the deep ocean is daunting: its size, darkness, crushing pressures, inaccessibility, complexity, and its many secrets. Perhaps that’s why we’ve managed to map only 25% of the seafloor at high resolution, even after successfully charting every last divot on Mars.