This is often followed by the offending dog adopting a play bow position – where they stick their haunches in the air, dip their head, and splay their paws out. It’s a signal that means, “this is not a real fight and that was not a real bite, so let’s keep playing!”

Even though the rules of the game are clear, dogs have not arrived at them through sophisticated moral reasoning. For them, these play norms are instinctive. But for humans, we can use language to debate precisely which behaviours are acceptable in games or in polite society, and codify them into secular laws or religious doctrine.

We can use our intelligence to grapple with the nature of good and evil, right or wrong, and ultimately justify or condemn our individual or group actions. This allows us to live in societies consisting of millions of individuals, all capable of following the same set of laws intended to keep the peace.

Animals, however, can create complex societies without necessarily appealing to moral reasoning. Dolphins can live in groups of hundreds of individuals, with an intricate system of friendships and rivalries, with individuals able to track who might owe them a favour or who has helped or harmed them in the past.

It’s true, of course, that animal societies are not the most peaceful. Both dolphins’ and dogs’ social lives sometimes devolve into the kind of violence and cruelty that the natural world is known for; red in tooth and claw. Dolphins can be violent and murderous towards each other. And some dogs are not always as kind and gentle as Ned; more than a dozen human fatalities attributed to dog attacks are reported each year in the UK.

But it’s humans, despite our capacity for moral reasoning, that are the real problem when it comes to violence and cruelty. And this is where we see that our unique brand of intelligence does not make us the nicest animal on the planet. In fact, we are more than likely the cruellest. It’s precisely because we are so darn smart that we can scale up our animalistic, violent tendencies to a level not seen in other species.

We have harnessed technology to invent weapons of mass destruction. We use our social cognition and language skills to deploy our vast armies in times of war. We use our capacity for moral reasoning to justify murdering our fellow humans by the millions for political or religious reasons that appeal to our sense of both rightness and righteousness. And we can produce arguments both for and against genocide, which makes our capacity for ethical thinking as much a liability as a boon.

Despite having brains that give humans a capacity for moral reasoning and empathy that outstrips other species, it is often the non-humans in our lives that exhibit more kindness overall. So if you believe that your dog really is a good boy, or maybe even the best boy like my pal Ned, you might very well be right. Your dog might be a better person than any human could ever hope to be.

Justin Gregg is a senior researcher with the Dolphin Communication Project and adjunct professor at St Francis Xavier University, where he lectures on animal behaviour and cognition.

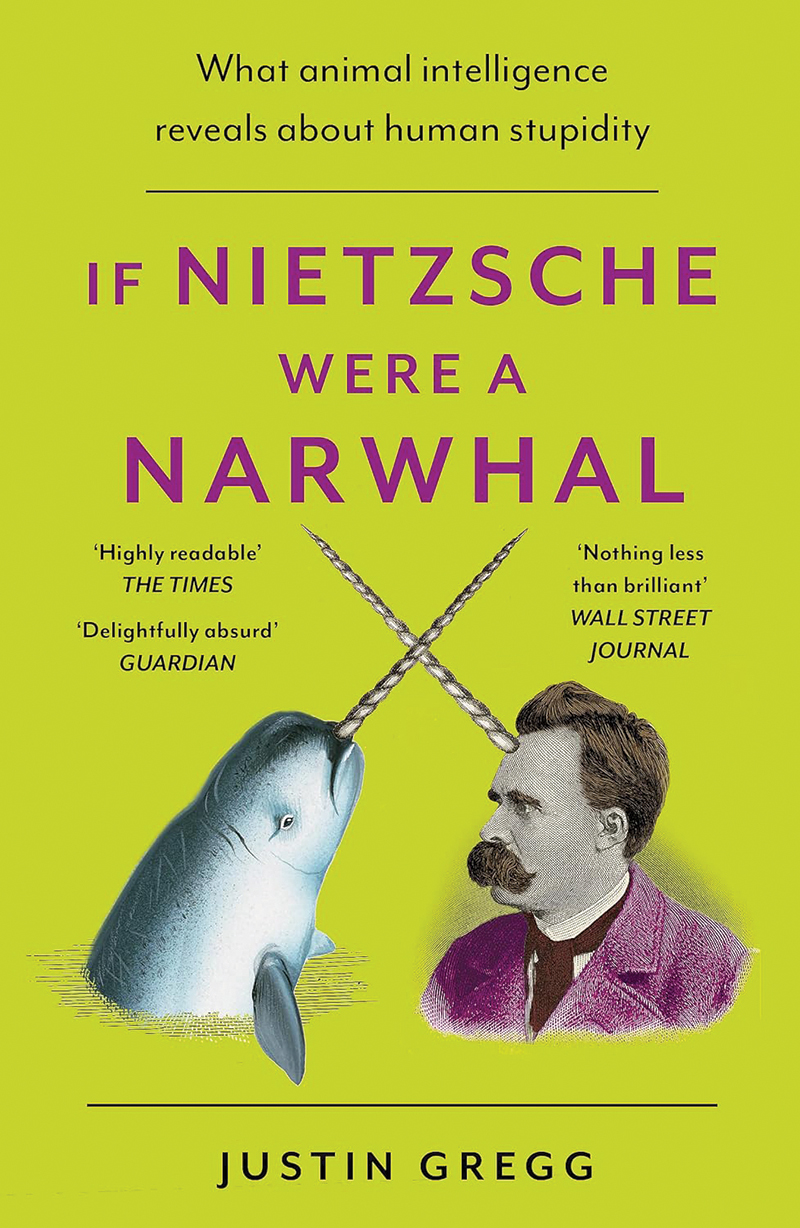

If Nietzsche Were a Narwhal by Justin Gregg is out now (Hodder & Stoughton, £10.99). You can buy it from The Big Issue shop on Bookshop.org, which helps to support The Big Issue and independent bookshops.

This article is taken from The Big Issue magazine, which exists to give homeless, long-term unemployed and marginalised people the opportunity to earn an income. To support our work buy a copy!

If you cannot reach your local vendor, you can still click HERE to subscribe to The Big Issue or give a gift subscription. You can also purchase one-off issues from The Big Issue Shop or The Big Issue app, available now from the App Store or Google Play