Outraged splutters were heard and pearls were clutched this weekend after The Telegraph revealed the Roald Dahl estate was tweaking the beloved author’s work for new editions. People – adults, incidentally – have been quick to cast the decision as another battleground in the culture wars: the woke mafia swooping in to sanitise another cherished pillar of British heritage.

Even from the more considered corners of literature the response has been broadly critical. “Roald Dahl was no angel but this is absurd censorship. Puffin Books and the Dahl estate should be ashamed,” Salman Rushdie posted on Twitter. Discussing Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’s Augustus Gloop, who in the new versions is “enormous” rather than “fat”, children’s author John Doughty told BBC Radio 4: “I think if you’re going to decide that, then the only answer is to put the book out of print. I don’t think you can say, ‘So let’s change Dahl’s words but keep the character’.”

Philip Pullman, arguably one of the best authors writing for young people today, broadly agreed, saying Dahl’s books should be left to go out of print rather than changed if people were unhappy with them. Even the Prime Minister has stuck his oar in, saying via spokesperson that “when it comes to our rich and varied literary heritage, the prime minister agrees with the BFG that we shouldn’t gobblefunk around with words.”

It’s easy to cast this stuff as culture war fodder. We’re living in a state of perpetual outrage of one form or another anyway. This is just another flaming bottle of petrol to fling into the melee. “How dare these sanctimonious wokies tinker with the sacred texts of snot and filth that have so delighted children for decades?”

Most people are missing the point. It was Philip Pullman who eventually hit the nail on the head. “It depends what sort of life we want them to have,” he said on Twitter. “If we want an old text to live as entertainment, there are plenty of dull things to cut as well as ‘offensive’ ones. But why not just let it go out of print? Oh. Of course. Money.”

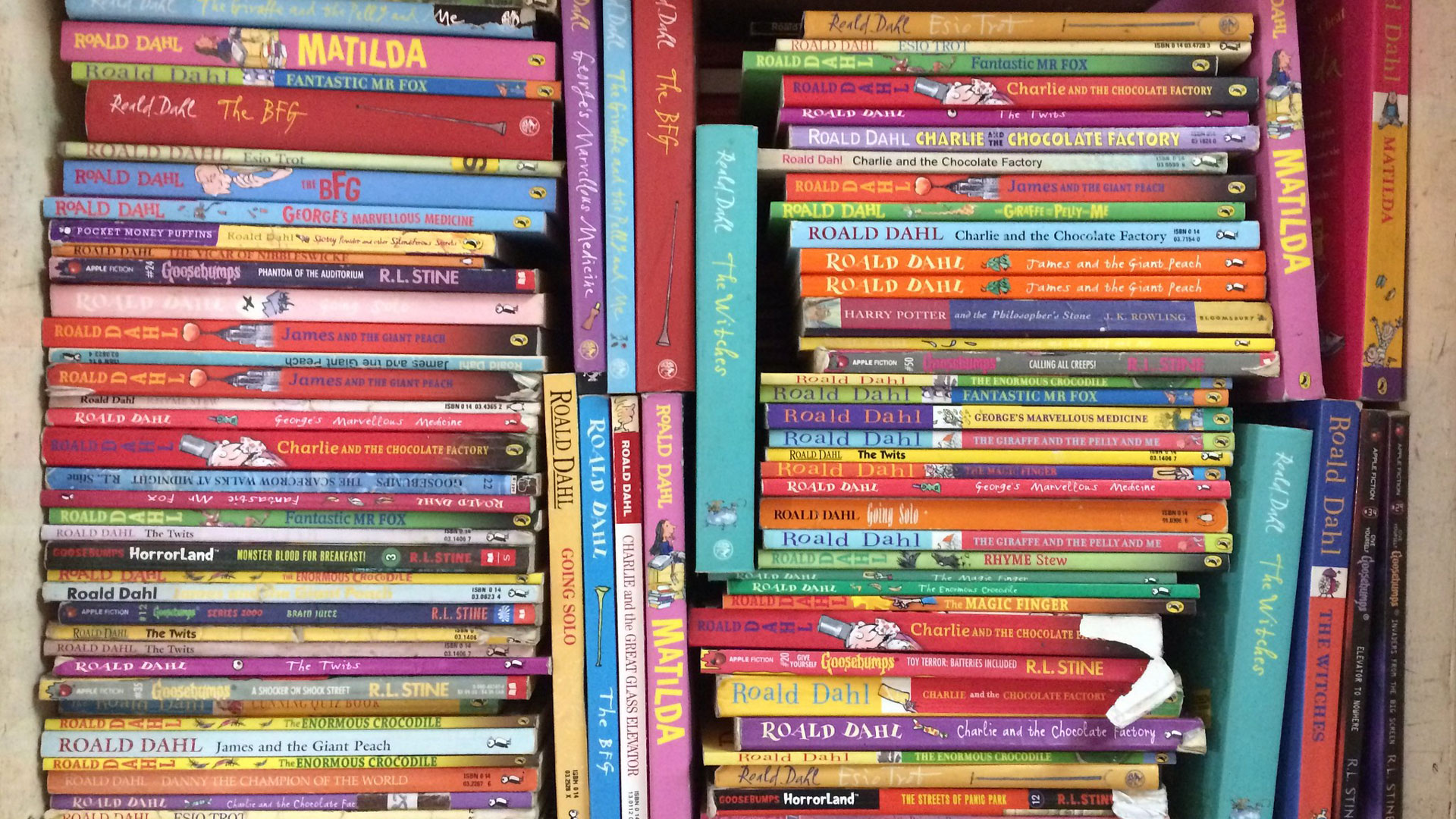

The Dahl estate, which is already sensitive about this stuff having issued a full apology for the author’s notorious antisemitism a few years back, knows the value of its product. Many years after his death, Dahl is still widely read by children – and with good reason, his books are wonderful. Just as revolting, just as funny, just as wildly imaginative as they always have been. This is about ensuring that children continue to think so. The suggested tweaks to the text might feel fairly incidental at the minute, but that’s not always going to be the case. Language changes, it becomes recontextualised, its power shifts. Societies change too. Our priorities evolve and swirl. Younger people have different cultural values to their parents.