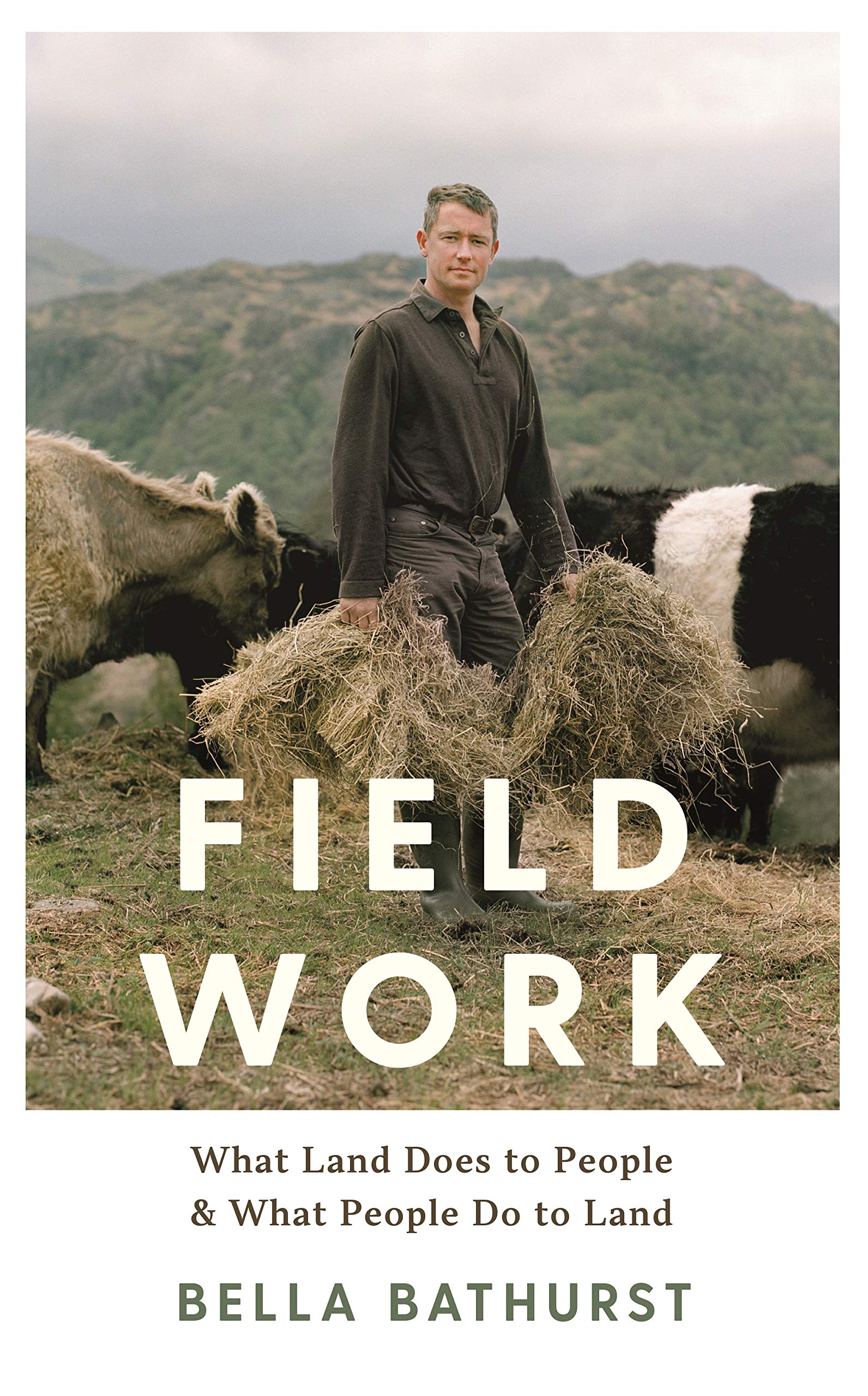

Seven years ago, I moved into a farm cottage on a hill near Wales. Rise Farm was run by Bert and Alison Howell, a couple in their seventies whose son had gone to live in Spain and whose main source of assistance was now their two collies – Bryn and a dog who for a long time I genuinely believed to be called Come Here You Useless Bugger.

Rise was one of a declining number of small farms making the best of the high places in the Black Mountains, places which would once have represented a generous living but which now struggled by on rents, subsidy and the heart-attack price of lamb.

Support The Big Issue and our vendors by signing up for a subscription.

The more time I spent with Bert and Alison, and the more I got to understand about the way the farming view of this world diverged from the non-farming one, the more compelling it seemed.

Farming seemed to embody so many switchbacks and contradictions. It was seen as insular, but expected to be global, a secretive industry which you could see from space, requiring everlasting reserves of emotional resilience from a group of people who never talked. It was seen as lazy and low-status, but I’d never come across a group of people who worked harder. It was seen as fixed, but most farmers were meant to be six professions in one day, from accountant to vet, mechanic to economist, midwife to chemist, manager to gambler. A gambler most of all.

Shakespearean family dramas unravelled over generations in places that only inspectors and vets ever went to. It lived by a set of different regulations, had separate lawyers and accountants, needed a separate government department, abided by footnotes, exemptions and addendums. It had done more to influence our history than half our wars. It seemed to be the exception to every rule, but it still provided the basics of existence.