THE day I began reading David Farrier’s Footprints: In Search of Future Fossils, the news headlines were dominated by the closure of the Queensferry Crossing. Some people were angry that the £35m bridge, built with 11ft barriers to protect it from high winds, had been put out of action by falling ice. Commuters were unable to get to work; tempers were fraying.

By coincidence, the first chapter of Footprints opens on the Queensferry Bridge. Farrier, an English lecturer at Edinburgh University – was one of those allowed to walk across the country’s newest stretch of road before it began taking traffic. He notices the “fist-like rivets [which] bulged from every knuckled stanchion” of a crossing built to handle 20m motorised journeys a year. Bereft of the cars it was built to carry, however, Farrier perceives it as a link between the pre-industrial past and the future: both “a pilgrim route made by tramping feet” and “a vision of roads to come, when the oil is gone and the engines are silent.”

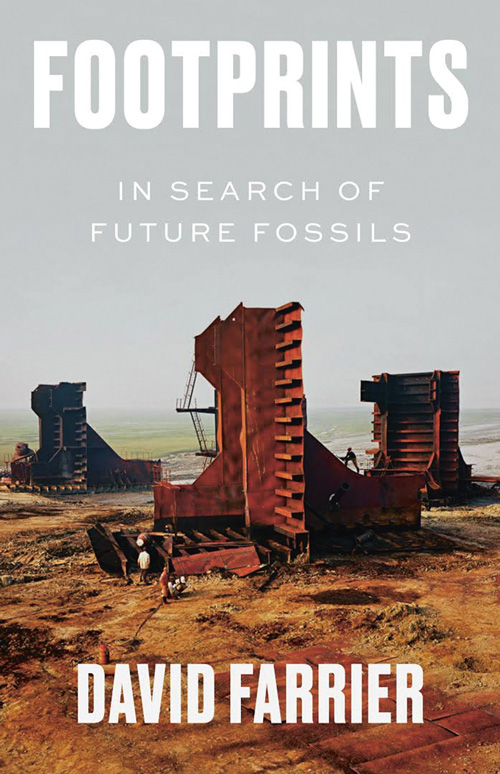

Like Robert Macfarlane’s Underland, Footprints is an indictment of the Anthropocene: a requiem for all that man’s greed is stripping from our planet, and an exploration of what traces we will leave behind in the rocks and glaciers. One day, Farrier predicts, roads like the Queensferry Bridge will serve as a fossilised testament to man’s hubris.

At his best, he is a beautiful writer. His visual descriptions are vivid, his musings profound

His writing is both forensic and elegiac. In some sections, our capacity for destruction is communicated through statistics. As he tallies the amount of junk in space, numbers smash into one another like vehicles in a pile-up. But the rest of the book is a switchback of cultural allusions.

In The Insatiable Road alone, we are taken on a journey through the works of David Hockney, Joan Didion, Ben Okri and Edward Byrtynsky. In Thin Cities we look at urban landscapes through the lenses of JG Ballard and Italo Calvino. It’s a dazzling, dizzying ride; but even more thrilling is when Farrier allows his own thoughts to cut through the cacophony of others’.

At his best, he is a beautiful writer. His visual descriptions are vivid, his musings profound. He sees a column of brain coral as “cascading lines of pinpricks like hundreds of minuscule mouths, gaping in petrified outrage” and the Shanghai Tower as “constantly engaged in imagining its own dissolution.”