About 16 months ago, I stood in what could have been a left luggage depot in Potocari near Srebrenica, surrounded by body parts in labelled plastic bags. Those bits of flesh and bones – a tibia here, a fibula there – were waiting for others from the same victim to be unearthed so a skeleton could be reassembled; so all the mothers who had lost their sons would have something tangible to mourn.

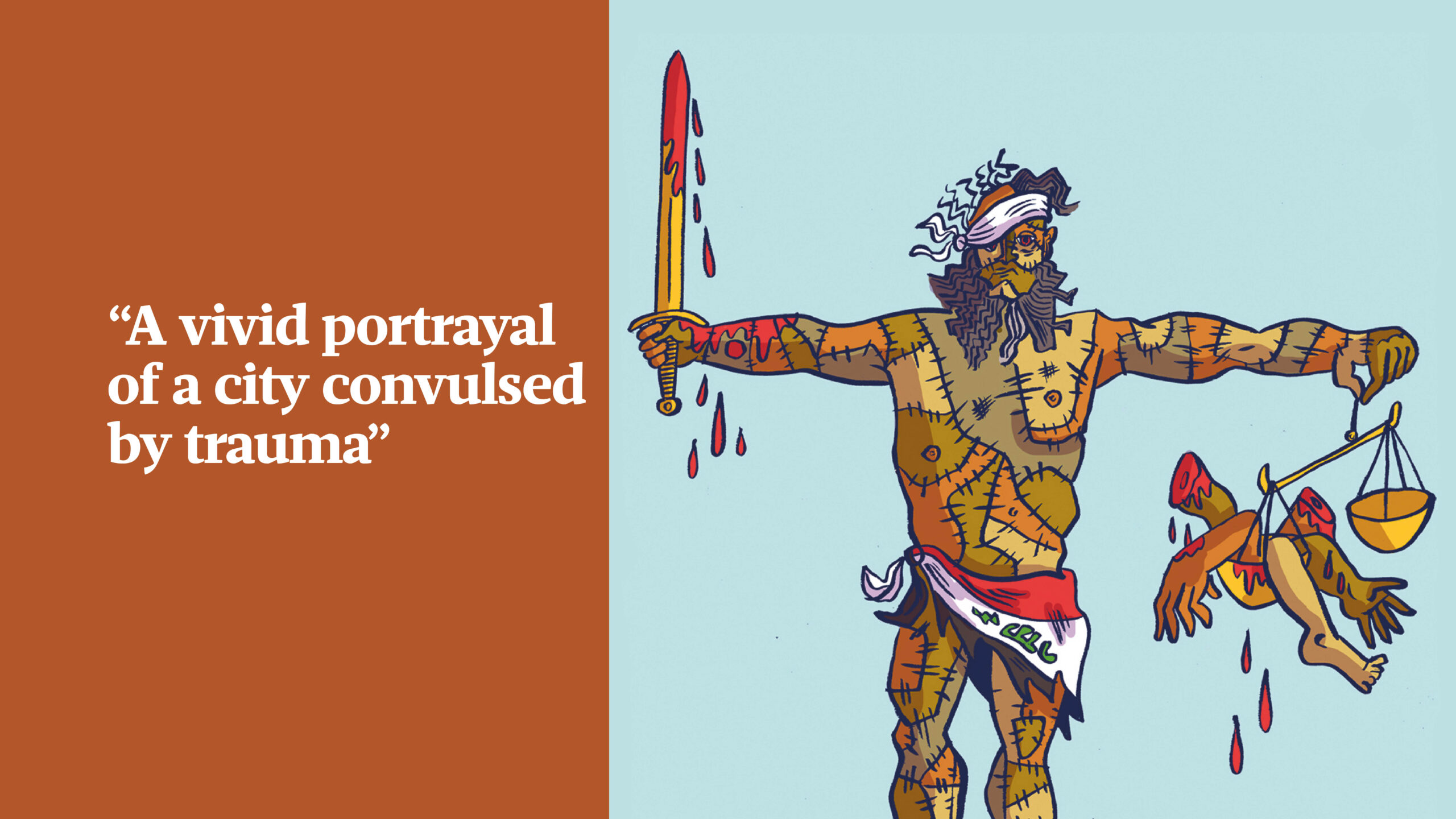

Ahmed Saadawi’s grimly funny novel Frankenstein in Baghdad is set in the city in 2005 when it is occupied by the Americans, and draws on that same hunger for physical restoration. Car bombs are exploding and human remains are scattered across every square. Devastated by the death of his friend Nahem, Hadi, the junk dealer, starts picking up corporeal shrapnel and sewing it together to create a new being he christens Whatsitsname.

His creature – the amalgamation of many innocent people – is brought to life by the restless soul of a murdered hotel security guard. Whatsitsname is the answer to resident Elishva’s nightly prayers and she claims him as her missing son, Daniel, forced off to war 20 years earlier; but he is also the manifestation of Baghdad’s collective grief. Like a putrefying Terminator, he embarks on a mission to avenge the deaths of his component parts, even as they are dropping off him.

Whatsitsname is the manifestation of Baghdad’s collective grief

Translated by Jonathan Wright, Saadawi’s book, winner of the International Prize for Arabic Fiction, is a vivid portrayal of a city convulsed by trauma. It is a city in the process of abandonment; many of its ordinary citizens have already fled leaving behind a gothic, almost hallucinogenic landscape populated by madmen and magicians, prophets, ghosts and portents of doom. In one striking tableau, four beggars are found dead in a lane, each one with his hands around the throat of another.

Whatsitsname stalks the liminal space between reality and urban myth. “There are laws that operate only under special conditions and when something happens under these laws, people are surprised and say it’s impossible,” writes magazine owner Ali Baher al-Saidi in his weekly column. His protégé Mahmoud al-Sawadi identifies three types of justice: legal justice, divine justice and street justice. But, as Whatsitsname quickly discovers, dispensing any kind of justice is complicated in a war with multiple factions and no frontline.

As he replaces decomposing body parts with fresh ones of unknown provenance, he is no longer sure how much of him is victim, how much perpetrator, and his violence, at first driven by righteous fury, degenerates into senseless carnage. Thus, the monster –chaotic, morally ambiguous and lurching out of control – becomes a powerful metaphor for all modern conflicts.