“The actual events in the book are quite sad and squalid, but through the eyes of Luci, who dresses everything in drag,” Morrison says of this tension. “It’s a pathos we all understand. We all try to make the world more magical, but underneath are the grinding mechanisms of time and the cruelty of life and death. I think people can empathise with Luci: she’s a difficult character, but she tries to dress everything up. Even the most awful things seem somehow magical when she describes them.”

Like many of Morrison’s creations before her, Luci shares their interest in the occult. Her totems are clothes and cosmetics; raw materials that enable her control of glamour – the specific magic of transformation and deception.

Costumes and fashion have always been important to Grant Morrison, from reading their mother’s Vogue magazines as a child to dressing their comic characters in facsimiles of their own outfits. It’s an interest that can be traced back to superhero costumes in comics:

“I love the colour combinations, the symbols,” they explain. “I also love materials, especially ’60s materials, plastic and shiny stuff. I got into the fetish scene because I love those kind of clothes. For me, it wasn’t even about sex, it was the idea of this fabulous future where we all look like our own superhero selves.”

This interest in clothing ran parallel to a specific interest in drag, which developed into a public persona after they found success in comic books in the late ’80s. “I’d made a bit of money and I was liberated from everything,” they say of the time in the ’90s where they began to indulge in magic, psychedelics and drag.

“I would combine stuff with these thuggish elements, so I would go out with a skinhead and Doc Martens, but I’d wear a dominatrix top with fake breasts, or I’d go out with high heels and a bra and a Bill Sikes cane. I was never going to go on Drag Race though, my makeup was terrible!”

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Morrison would wear full drag during magical rituals, a persona which manifested in their ’90s masterwork The Invisibles as Lord Fanny, an “unbeatable witch dominatrix”. Morrison sees Luci LaBang as Lord Fanny reprised, “with the cares and the woes that have occurred in between”, and Luda as a way of enacting their “final drag performance”, enshrining an important part of their life in their work.

Lord Fanny and Luci LaBang are just two of the many characters through which Morrison has expressed different aspects of their life and self – from The Filth’s Greg Feely, whose only friend is his cat, to the “female trilogy” of Emma Frost, Jean Grey and Siryn in X-Men.

Morrison compares these various self-insert characters to songs that all exist in tandem: “They all have a reason to be. You can write a song when you’re broken-hearted. You can write a song when you’re joyous. None of them represent who you are, just a song about that feeling that day.”

Self-insert characters are also a reflection of what Grant Morrison describes as their “multiplex personality” – the sense that some of us contain multiple selves, and can’t be readily categorised.

“It’s kind of why Luda isn’t about trans issues at all, because it’s about performance and deception, which is the opposite of trans issues, which are about trying to be yourself. Luda’s about people like me,” says Morrison, whose identification as non-binary feels more like a refusal than a definition of their gender, and by extension, their whole self.

“I feel there’s lots of me. I love being a really tough guy some days, and I love being a wilting poet other days. I’d feel neutered if I couldn’t be all these things. The notion that we can be labelled and be the same forever, I’m fundamentally opposed to.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

“Comics gave me the model for how the inside of my head worked,” they continue. “When I look inside there’s a joker, there’s a depressive, there’s a fabulous genius, there’s an idiot… over the years I’ve learned to get them in a Justice League around a table so that we kind of work properly. I can rotate those characters around.”

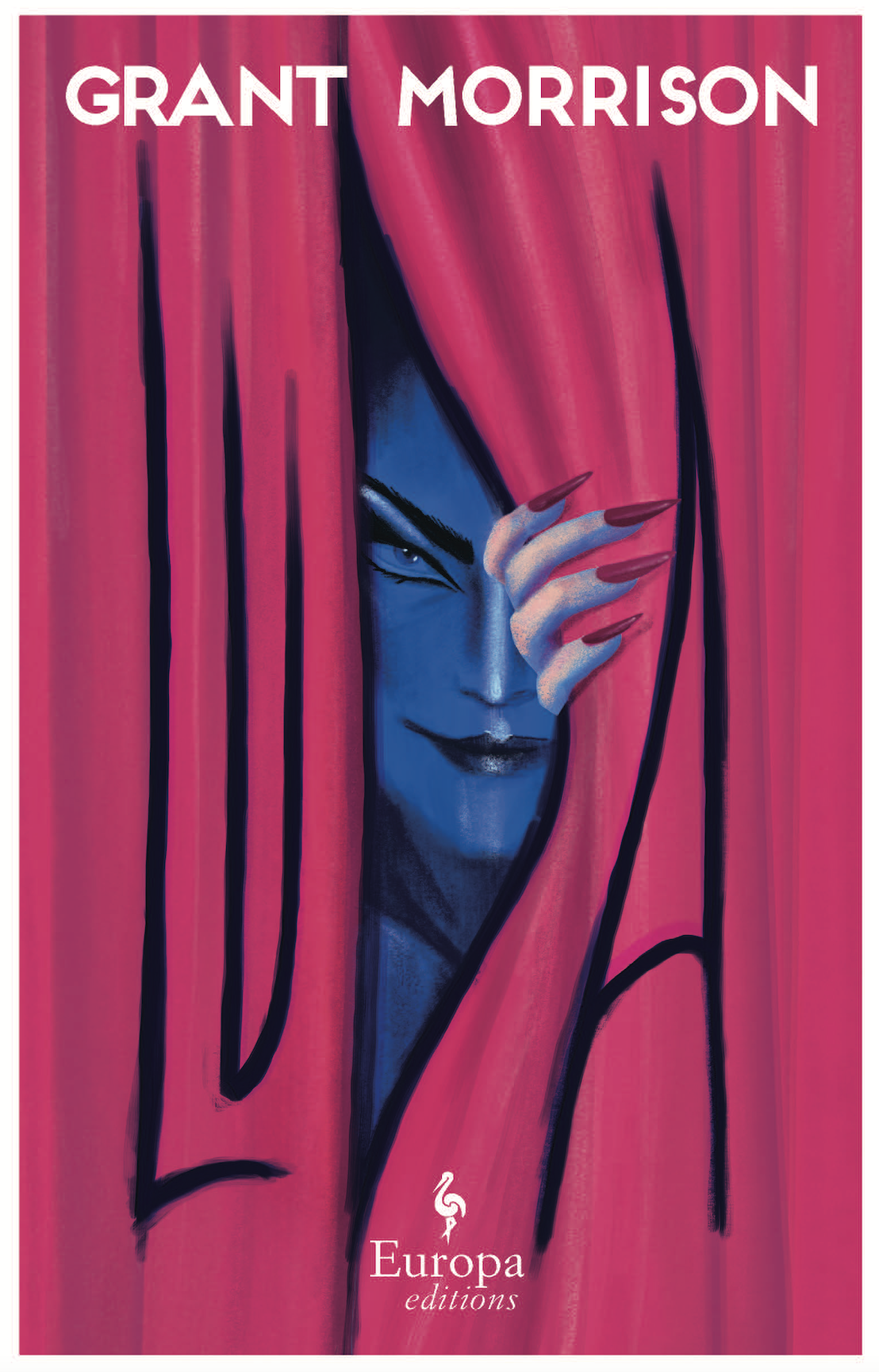

Luda: A Novel by Grant Morrison is out now (Europa Editions, £15.99).

This article is taken from The Big Issue magazine, which exists to give homeless, long-term unemployed and marginalised people the opportunity to earn an income. To support our work buy a copy!

If you cannot reach your local vendor, you can still click HERE to subscribe to The Big Issue today or give a gift subscription to a friend or family member.

You can also purchase one-off issues from The Big Issue Shop or The Big Issue app, available now from the App Store or Google Play.