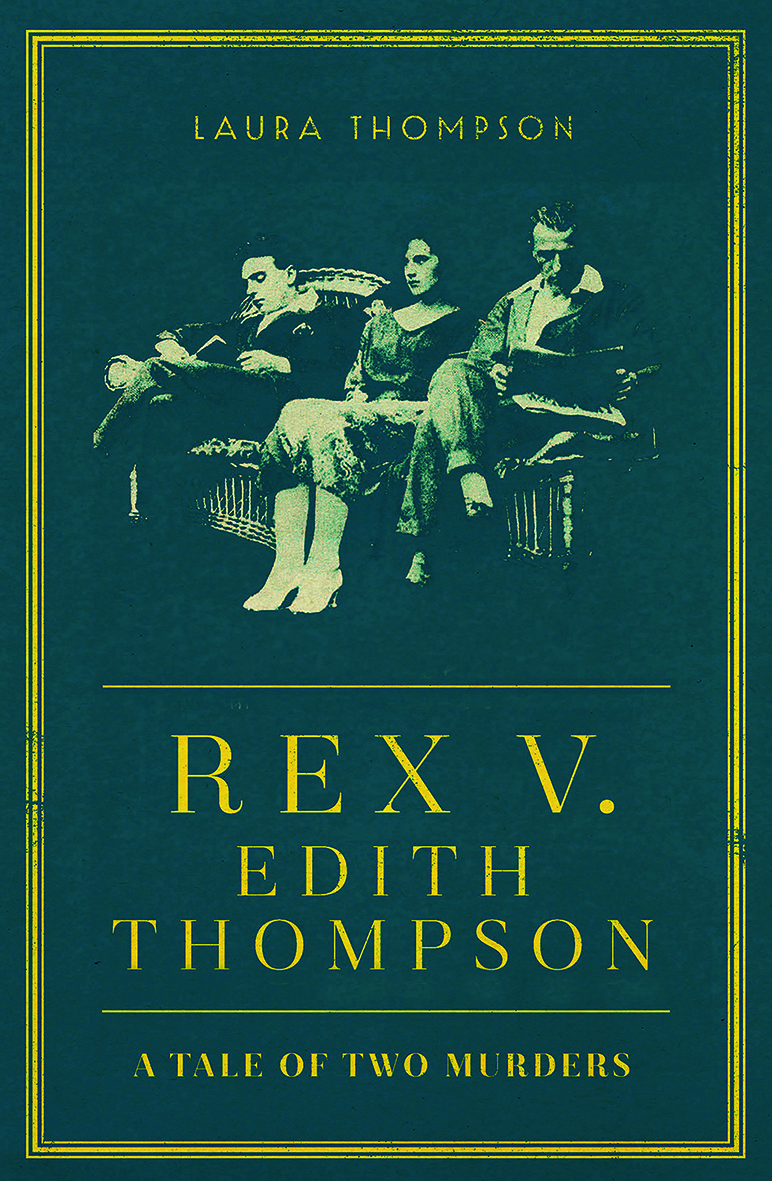

In January 1923 Edith Thompson, aged 29, and her lover Frederick Bywaters, aged 20, were hanged for the murder of her husband. Bywaters had stabbed Percy Thompson during a scuffle on a street close to the couple’s home in Ilford. Although Edith was present it was never suggested that she played a physical part in the killing, but she was found guilty of conspiracy: of foreknowledge and incitement.

As sentence was pronounced she screamed: “I am not guilty! Oh God, I am not guilty!” Meanwhile a Home Office file, held under the 100-year rule and prematurely opened, recorded that on the morning of his execution Bywaters said: “Mrs Thompson knew nothing about the crime.”

It was not the first time that he had made this statement. The actual evidence against Edith Thompson was pretty much non-existent, but it made absolutely no difference. The presumption, from the first, had been that hers was the hand that had metaphorically guided the knife. Almost everybody wanted to think this, and sympathy was almost entirely for Bywaters. As the magistrate at the initial hearing put it: “He was exposed for many months to the malign influence of a clever and unscrupulous woman eight years older.”

It was an absurd simplification – the handsome merchant seaman Bywaters was no innocent – but it was the narrative that everybody craved, and none more so than other women. The author Rebecca West was a self-proclaimed feminist; nevertheless her belief in the sisterhood did not extend to the notorious Mrs Thompson, whom she dismissed as “a shocking piece of rubbish”. Everything about Edith invited prejudice from one quarter or another: she was disturbingly sexy, she was a self-centred career woman (a manager in a wholesale millinery firm) and – like Lady Macbeth, that other great inciter – she had no children. She did not know her place, and she did not fit.

It was not exactly a pleasure to write about

Even today, she would arouse strong feelings among the commentariat. Bywaters would still, for some, be viewed as the plaything of his rapacious cougar. Back in 1922, meanwhile, she had no chance whatever. This lower-middle-class East London girl – who had sought to shape her own destiny, as far as was possible within the twin circumscriptions of class and gender – was fated to become one of those sacrifices that society periodically demands.

I first read about the Thompson-Bywaters case as a teenager. Since then it has been under my skin. It was not exactly a pleasure to write about (although it seems presumptuous to say that I found it painful, given what the protagonists endured) but I wanted desperately to do so. The story is not unknown; however mine is the first account to have used all the information previously held under the 100-year rule. This includes eyewitness reports of Edith Thompson’s execution, about which rumours – notably that she was pregnant – have abounded ever since.