When it comes to Jane Austen there turn out to be a lot of unknown knowns. For decades, we’ve prioritised family stories and unevidenced claims over the provable facts of Austen’s life and the words that she wrote. Almost all of us are guilty of doing this to some extent, including biographers and academics.

Austen was writing light-hearted romances. She had no interest in politics, nor in current affairs. You would have no idea, reading her novels, that she lived through the best part of a quarter of a century of war. These assertions have been made for decades, repeated again and again with so much certainty that many readers have started to believe them.

Winston Churchill envied the characters in Pride and Prejudice for their “calm lives” and lack of concern about “the crashing struggle of the Napoleonic Wars”: early on in the novel a regiment of defence militia appears in the heroine’s hometown. There are soldiers or naval officers in every single one of Austen’s six completed books, while the entire action of Persuasion, the last novel she completed, takes place during the months that Napoleon was confined to Elba, ending the very week he escaped.

Sense and Sensibility shows men taking things from women: their reputations, their money, their homes. In one alarmingly Freudian scene, a prominent male character picks up a pair of scissors and proceeds to ruin “both them and their sheath by cutting the latter to pieces”. Mansfield Park is full of references to slavery.

We know from references in her letters and her fiction that Austen read both feminist and abolitionist authors, so it seems unlikely that any of this can be accidental but readers sometimes doubt the evidence of their own eyes. I’ve taught students who visibly struggle to accept that Austen can possibly mean what she’s written.

Northanger Abbey, Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice were all originally begun at the end of the 1790s but not published until 10-15 years later, by which time the significance of some of their contemporary references had already been lost. Austen expressed her concern about this in an author’s note prefixed to Northanger Abbey. But if success was slow to arrive, it’s also become part of the problem.

We don’t know or care much about the lives of most authors. Few have been the subject of multiple biographies and biopics, still fewer have had their works repeatedly reimagined, updated and expanded, or turned into television and film adaptations which are watched and re-watched by millions around the world. Austen is a juggernaut now, a huge and profitable industry and it’s become increasingly difficult to see the novels she wrote without being influenced by all the subsequent interpretations that have collected around them.

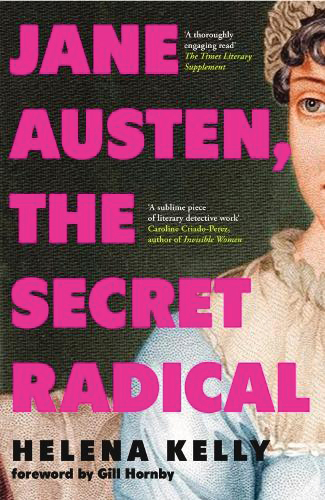

In writing Jane Austen, the Secret Radical, I attempted get back to the texts themselves, to place them in the time and context that they were written, to spell out the in-jokes and literary references and political debates that Austen would have been expecting her audience to understand. The hope is that we can get closer to the novels that Austen wanted us to read.

Jane Austen, the Secret Radicalby Helena Kelly is out now (Icon Books, £10.99).You can buy it from The Big Issue shop on Bookshop.org, which helps to support The Big Issue and independent bookshops.

Do you have a story to tell or opinions to share about this? Get in touch and tell us more. Big Issue exists to give homeless and marginalised people the opportunity to earn an income. To support our work buy a copy of the magazine or get the app from the App Store or Google Play.