JRR Tolkien’s first novel, The Hobbit, begins with an unexpected visit by the wizard Gandalf to the home of Bilbo Baggins, but the Hobbit himself – the book or the character – was perhaps at least as unexpected for the author. Moreover, Baggins might have been somewhat unwelcome, for Tolkien later complained that he was far more interested in the connected body of legends that he had been working on – his “private and beloved nonsense” that would form the basis for The Silmarillion, but which was left incomplete and unfinished during his lifetime.

Tolkien complained that Bilbo Baggins “intruded” or “got dragged” into that history “against my original will”, and initially he resisted the idea of writing a sequel. That sequel was The Lord of the Rings, one of the most famous English novels of the 20th century, and the foundational text for the modern fantasy genre. Ironically, then, with the publication of The Hobbit in 1937, the intrusion of Bilbo Baggins into Tolkien’s imaginary world, and into our own world, is what made Tolkien’s elaborate history and geography of Middle-earth available to us.

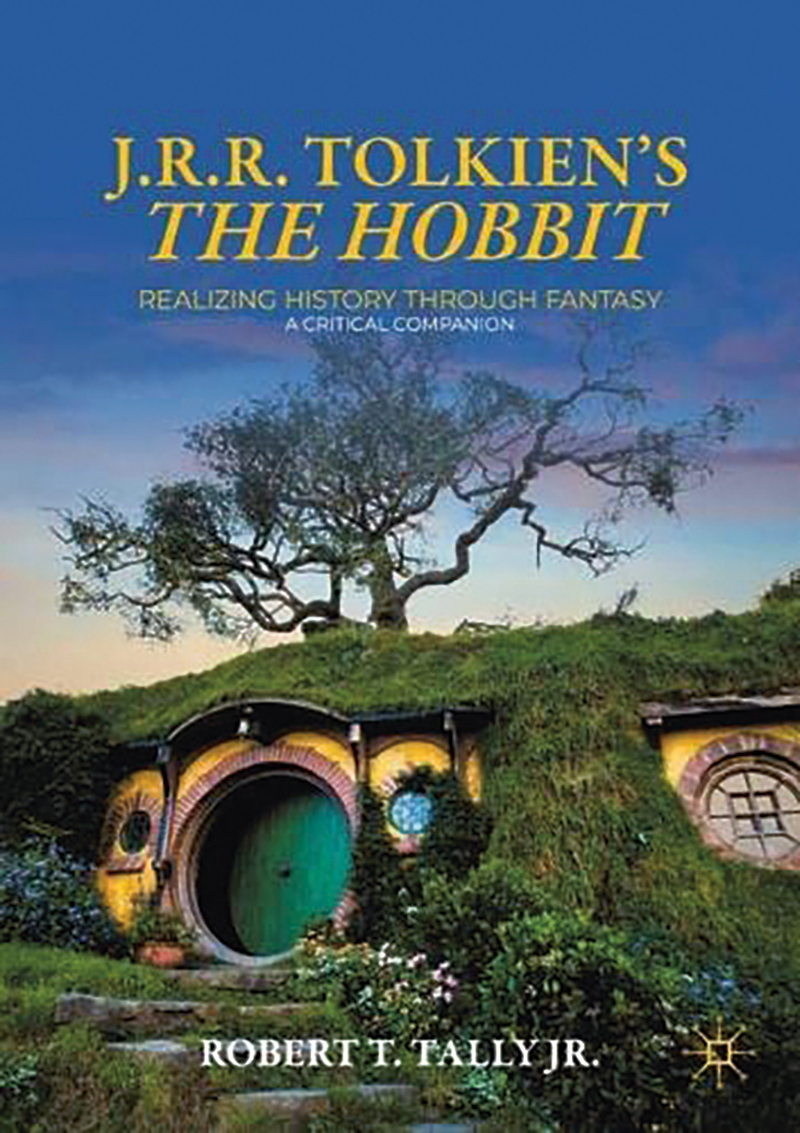

In my new study, JRR Tolkien’s The Hobbit: Realizing History Through Fantasy (out next month), I aim to provide a critical introduction and companion to Tolkien’s classic novel. I believe that, contrary to first appearances, The Hobbit is a historical novel. It does not refer directly to any “real” historical events, of course, but it both enacts and conceptualises history in a way that makes it real. Tolkien’s devotion to myth-making is, in large part, impelled by a desire to bring the historical register to life via storytelling. The form of the heroic romance is thus both employed and subverted by Tolkien in his tale of a most unlikely hero, “quite a little fellow in a wide world”, who nonetheless makes history.

The “realisation” of history is an important aim of Tolkien’s art. Tolkien’s yearning for a mythic past, despite its clear nationalism and chauvinism at times, reflected a deep desire to connect his modern world with an august, barely accessible past through forms of historical narrative. This is not the “escape” into a mythical, premodern realm that is frequently imagined by fans and detractors of Tolkien’s writing alike. Rather, Tolkien’s is an attempt to take the broken and disconnected fragments of culture and put them together into a meaningful history, evoking what he would call “the seamless web of story”.

In a well-known letter to WH Auden, Tolkien explained that the value of hobbits lay “in putting earth under the feet of romance”, ie demonstrating the way that simple, ordinary folks may prove truly heroic, more so than even epic heroes, when circumstances called for it. Tolkien’s vision is akin to what the British historian EP Thompson famously called “history from below”. Tolkien firmly believed that, as he put it in another letter, “the great policies of world history, ‘the wheels of the world’ are often turned not by lords and governors, even gods, but by the seemingly unknown and weak”.

In The Lord of the Rings, he has Elrond enunciate this view, noting that “deeds that move the wheels of the world” are often the work of “small hands”. Hobbits are literally made small, of course, but they also symbolise “petty” or “plain unimaginative parochial” people, while representing “the amazing and unexpected heroism of ordinary men in a pinch”.