An abortion that led to vaccines that have protected hundreds of millions of people? The long-buried story, flagged in a letter to the editors of Science magazine in 2012, seemed to shout to me that it ought to be made into a book. So I sought out the letter-writer, Leonard Hayflick, a vigorous, 80-something biologist living in northern California – and he told me the amazing tale of the cells that he derived from an aborted foetus in 1962.

I soon discovered that the story was full of stranger-than-fiction characters and events: strong-headed, larger-than-life scientists, orphans and Archbishops, court battles and cell “kidnappings” – and dire, once-dominant diseases that have since been quelled by vaccines.

It all began with an anonymous Swedish woman, whom I call Mrs. X. Married to a feckless husband, she had several children already. She decided she could not face having another baby. In Sweden in 1962, abortion was legal but not readily available. Most doctors refused to offer the procedure. By the time she found a sympathetic, female gynecologist, Mrs. X was four months pregnant.

The story was full of stranger-than-fiction characters and events: strong-headed, larger-than-life scientists, orphans and Archbishops, court battles and cell “kidnappings”

After the abortion, her 8-inch-long, female foetus was taken without her knowledge and its lungs dissected at the famous Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. The tiny purplish organs were packed on ice and flown to Philadelphia. There, the young Leonard Hayflick worked in an elegant brownstone building on the University of Pennsylvania campus: The Wistar Institute of Anatomy and Biology. Hayflick’s brilliant, visionary and ruthless boss was the polio vaccine pioneer Hilary Koprowski, a Polish émigré who had recently turned the once-dying institute into an international crossroads of top biologists.

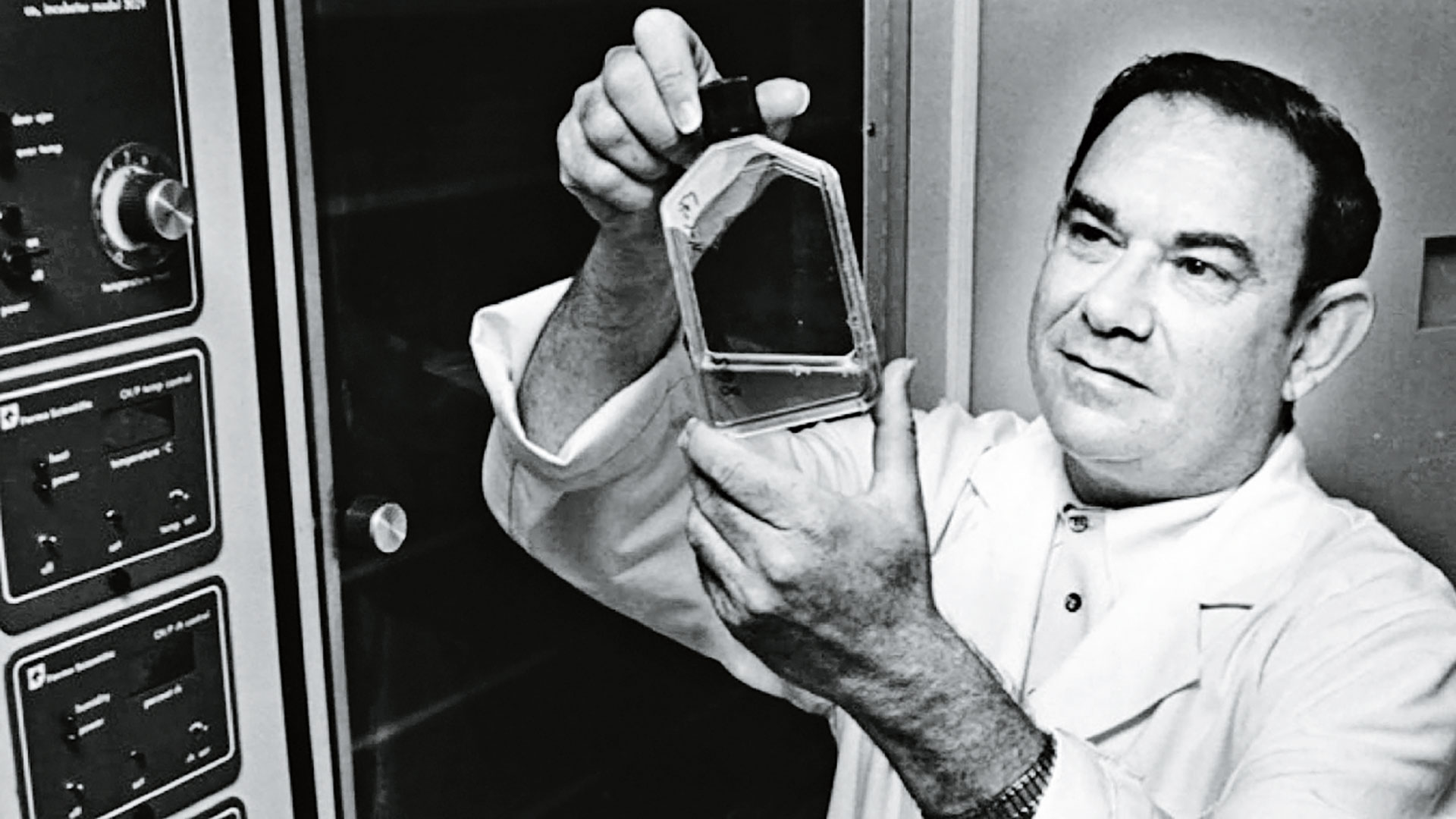

Hayflick had a PhD in medical microbiology but in the urbane Koprowski’s eyes, Hayflick was a mere supporting actor, hired to serve up lab-grown bottles of cells to the Wistar’s star-studded cast of scientists. But Hayflick, with his crew cut and working class Philadelphia roots, was not about to be overlooked. In the summer of 1962, he was keenly aware that silent monkey viruses had been found in the monkey kidney cells used to grown the famous Salk and Sabin polio vaccines.

One of these, SV-40, had recently been shown to cause lethal cancers in laboratory hamsters. Regulators were trying to downplay the news, but Hayflick was persuaded that normal, healthy cells from a single human foetus with healthy parents would provide a much-preferable alternative to monkey cells for making vaccines against viral diseases like polio, measles and rubella, also called German measles.