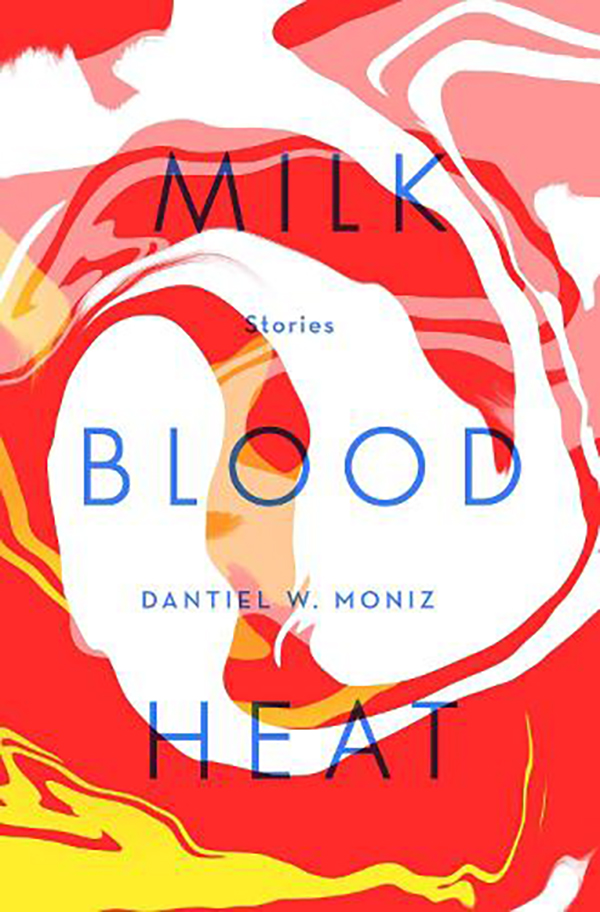

In the opening (and title) short story of Dantiel W Moniz’s outstanding debut collection Milk Blood Heat, two girls – one black, one white – on the cusp of adolescence slice their palms, mix their blood into a bowl of milk until it turns a cloudy pink and then drink it, absorbing each other both figuratively and literally.

This act – at once intimate, transgressive and ritualistic – establishes the atmosphere of the book, which has female experience, bodies and boundaries as its core, and thrums with a sticky sensuality. The situations Moniz’s characters encounter are familiar – sibling rivalry, infidelity, rebellion – but her perspective is so unusual, and her descriptions so visceral, her stories are a dark but thrilling joyride off the beaten track.

Support The Big Issue and our vendors by signing up for a subscription.

Much of the book is preoccupied with mortality. In Feast, Rayna, who has suffered an early miscarriage, sees tiny body parts everywhere – “a pair of miniscule hands floating above the curtain rod” and “lungs the size of kidney beans wheezing from the nightstand”. The blood-quaffing teenagers Ava and Kiera compete to imagine brutal deaths until the lines between fantasy and reality blur.

At times, Moniz’s writing has an almost hallucinogenic quality; it reads like a mad reverie brought on by the humidity of her native Florida, where much of it is set. Rayna, who dreams about fleeing west, muses: “Out there, I would track vipers through the bleached sand and lie beneath the moon’s cool regard, my belly full and swaying with meat.” There are moments of high gore, and undercurrents of cannibalism and autosarcophagy. In one story, a mother serves her daughter roasted beets, telling her “in my house, we eat the hearts of our enemies”.

Despite all its gothic pretensions, Milk Blood Heat is a celebration: of fraught but fierce relationships, and life in all its fractured glory

Some of Moniz’s characters are angry or damaged. In Tongues, Zey, castigated by a zealous pastor for the sins of Eve, remembers how, in her library books, “men’s fury stained the pages, sowing lies like white seeds inside of people’s hearts’’. In Thicker Than Water, the main character carries her past trauma as a literal burden, her father’s ashes in an urn to be scattered in Santa Fe.