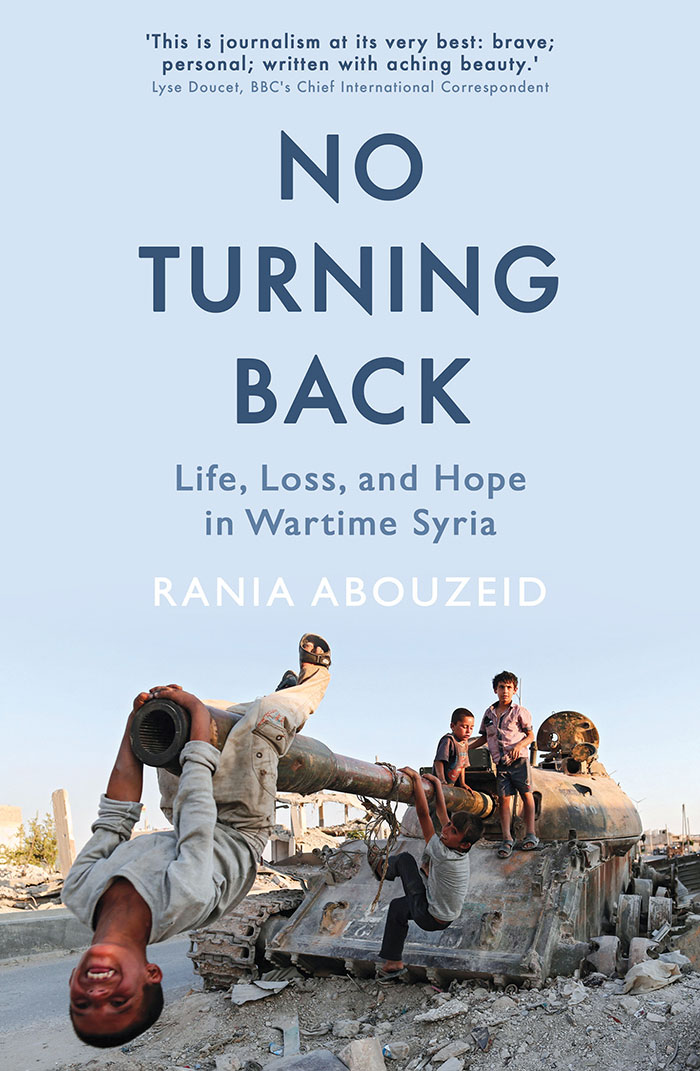

Minutes after finishing journalist Rania Abouzeid‘s book No Turning Back: Life, Loss and Hope in Wartime Syria, I switched on the news and saw footage from a hospital in rebel-held Eastern Ghouta.

The images were all-too familiar: doctors inured to the constant shelling; parents clutching bloodied children and an all-pervasive sense of futility in a conflict that, six years on, shows no sign of abating.

Despite its subtitle, No Turning Back is a bleak read, offering little prospect of a happy ending. But it is also a masterpiece: a forensic, yet accessible anatomy of how a peaceful uprising was hijacked by external forces who cared less about ridding Syria of dictator Bashar al-Assad than furthering their own agendas.

The book’s power lies in Abouzeid’s telling of the story through the contrasting perspectives of individuals who have given her almost unfettered access to their lives

For those confused by the country’s descent into chaos and the myriad factions now battling it out for supremacy, it is indispensable. Abouzeid, who has written for The New Yorker and Time Magazine, charts the civil war from the demonstrations of the Arab Spring (2011), through the rise and fall of the Syrian Free Army (SFA) and the influx of foreign jihadis, to the eventual formation of ISIS.

The book’s power, however, lies in Abouzeid’s telling of this complex story through the contrasting perspectives of a handful of individuals who have given her almost unfettered access to their lives. They include Suleiman, a wealthy young man from the once Assad-loyal city of Rastan; Ruha, a nine-year-old, living under continual bombardment in Saraqeb, Abu Azzam, a student-turned fighter in the Farouq Battalions (part of the SFA), and Mohammad, a prison-radicalised extremist who joins the Al Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra.

Travelling alongside them as events unfold, the reader not only shares in their mounting despair, but gains an insight into how the manipulation of a home-grown liberation movement into a quest for an Islamic caliphate was facilitated by the use of Syria as a proxy for other countries’ battles, by foreign states “playing favourites with groups on the ground” and by the West’s failure to act even as Assad was launching chemical attacks on his own people. ISIS planted its black flag in the midst of that discord, and, much as its ideology was despised, it brought a brutal form of order to a state of anarchy.