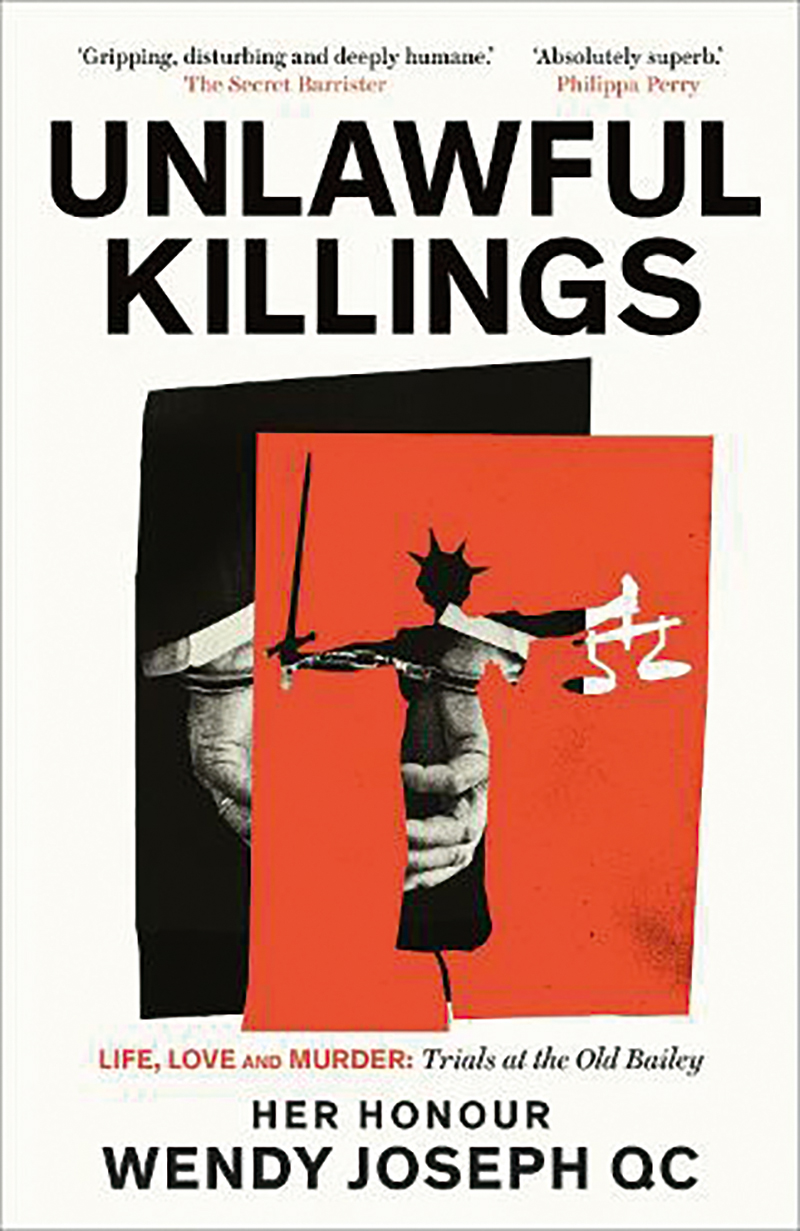

For the last 10 years I’ve sat as a judge at the Old Bailey. Now retired, I can look back at those years, pick up a pen and write about them. Almost every case I did there had a dead or nearly dead body in it. Murder, manslaughter and the infliction of appalling injury was my daily diet and a daily world of grief for victims and defendants, for their families and friends.

Yet almost every terrible incident was utterly needless, utterly pointless. Put like that, you might wonder why anyone does my job. But I could put it another way. I could say that day after day I presided over a courtroom where 12 people like you sat as a jury, weighing the evidence, searching for the truth. Each juror had left behind their own problems to sort out the mess that others had made of their lives. Each case brought its own characters to be understood, motives to be unravelled, plans and methodology to be exposed. Each involved human good and bad. Sometimes very bad.

The world of the courtroom is one in which any of us could find ourselves; as victim, witness, juror, or even – given the wrong circumstances – as defendant. Yet many people have only a foggy idea of what happens there. That isn’t their fault. It’s ours – the lawyers. So I have written this book to let daylight in on the system.

The law sounds complicated but it is possible to make it accessible to everyone. In this belief, I’ve begun the book with a group of schoolchildren, exploring the courtroom for the first time. Over the years I held many such visits. They were always a learning curve for me as well as for the kids.

After this introduction I have told six stories centred on worrying aspects of crime – knives, gangs, sexual abuse, mental illness and domestic violence. I’ve drawn on the hundreds of trials on which I sat, in order to say something true about them. I’ve tried to show what it feels like to sit in judgement on another human being; to look into the eyes of a 17-year-old and send him to prison for life, to see the grief of parents following the way that led their child to the mortuary slab, to help still-shocked witnesses recount what they saw and to guide the jury through the pitfalls of the law.

In the first story, Fiery Furnace, 16-year-old Daniel runs into a blind alley from which he will never find a way out. Then as the trial unfolds, we see how the attack on him came about. The court – and the reader – has to think about what makes boys carry knives, and what we might realistically do to stop them.