Essex is home to the second-largest coastline in England, so it’s perhaps unsurprising that it provides the perfect introduction for a budding marine biologist. Rummaging around the mudflats in search of minibeasts and accompanying my dad on sea angling trips out of the Blackwater Estuary were the bread and butter of my upbringing. Even now, despite living over an hour from the coast, feeling the blisteringly cold salty water wash across my skin is my escape from everyday chaos. I always take a dip in the ocean, even in the height of a January winter, to reconnect with my first love.

And yet, the dream of becoming a marine scientist always felt like it belonged to distant seas. Nature documentaries and books that so often focused on far-flung shores were my gateway to the global ocean. I fell in love with the beauty of tropical coral reefs in the Pacific and the remoteness of the Southern Ocean through the screen. It seemed to pursue my passion for marine conservation; I should look further afield than my own shores. Somehow, I needed to immerse myself in the kelp forests of South Africa or snorkel around a coral atoll in the Maldives. I was infatuated with the romantic idea of spending my days surrounded by endless blue in search of the next big scientific discovery, defending the sea from abuse and exploring the deep like Jacques Cousteau.

Soon though, the realisation of the expense of pursuing this career sent all my dreams crashing. Originating from a family that didn’t have prior experience of university, I struggled to identify how I could make this dream a reality. Being a marine scientist appeared to be an exclusive club. Pay-to-volunteer experiences and unpaid internships are rife in conservation, and I didn’t have that luxury. When I eventually made it to university, I spent more time in part-time work to pursue these experiences abroad than I did in my university lecture hall.

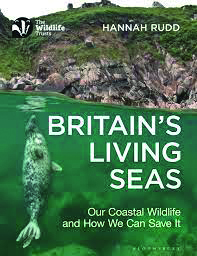

But you don’t need to go to the other side of the world to seek these interactions. The British coastline is also home to enormous whales, stealthy sharks and playful seals. Weird and wonderful species like the fried egg sea slug, baked bean sea squirt and dead man’s fingers are just as worthy of your attention. While the warmth of Australia or the isolated atolls of Raja Ampat are spectacular, you can also indulge in endless curiosity and wonder on our shores. Why were Britain’s seas not the focal point of blue-chip nature documentaries like the BBC’s Blue Planet?! And so, my book Britain’s Living Seas: Our Coastal Wildlife and How We Can Save It was born.

Amidst a climate and nature emergency, we often forget that we also face an ocean emergency. The ocean remains out of sight, out of mind, for so many of us, and yet I believe that if many of the things that happened at sea happened on land, we would be quicker at dealing with them. And while the devastating state of our global ocean is deeply depressing, there remains so much to be optimistic about. Across the country, communities are acting for an ocean-positive future. Working in tandem with nature through marine protected areas and restoration projects like the Essex Native Oyster Restoration Project and Project Seagrass, we can turn the tide on the ocean crisis. Nature has an incredible way of bouncing back if we give it the opportunity.

- What 4,756,940 pieces of Lego lost at sea tell us about our attitudes to plastic pollution

- Tory MP suggests home drainage systems are to blame for sewage being dumped in the sea

- How you can act on ocean pollution this World Oceans Day

As a coastal nation, we have an abysmal lack of connection with our seas and unequal access to the shoreline is a significant barrier to overcome that. As people flocked to our coastal fringes during the global pandemic, many discovered a newfound appreciation for our seas. But many of us also found it challenging to access the coast as prices skyrocketed and these spaces became more exclusive.