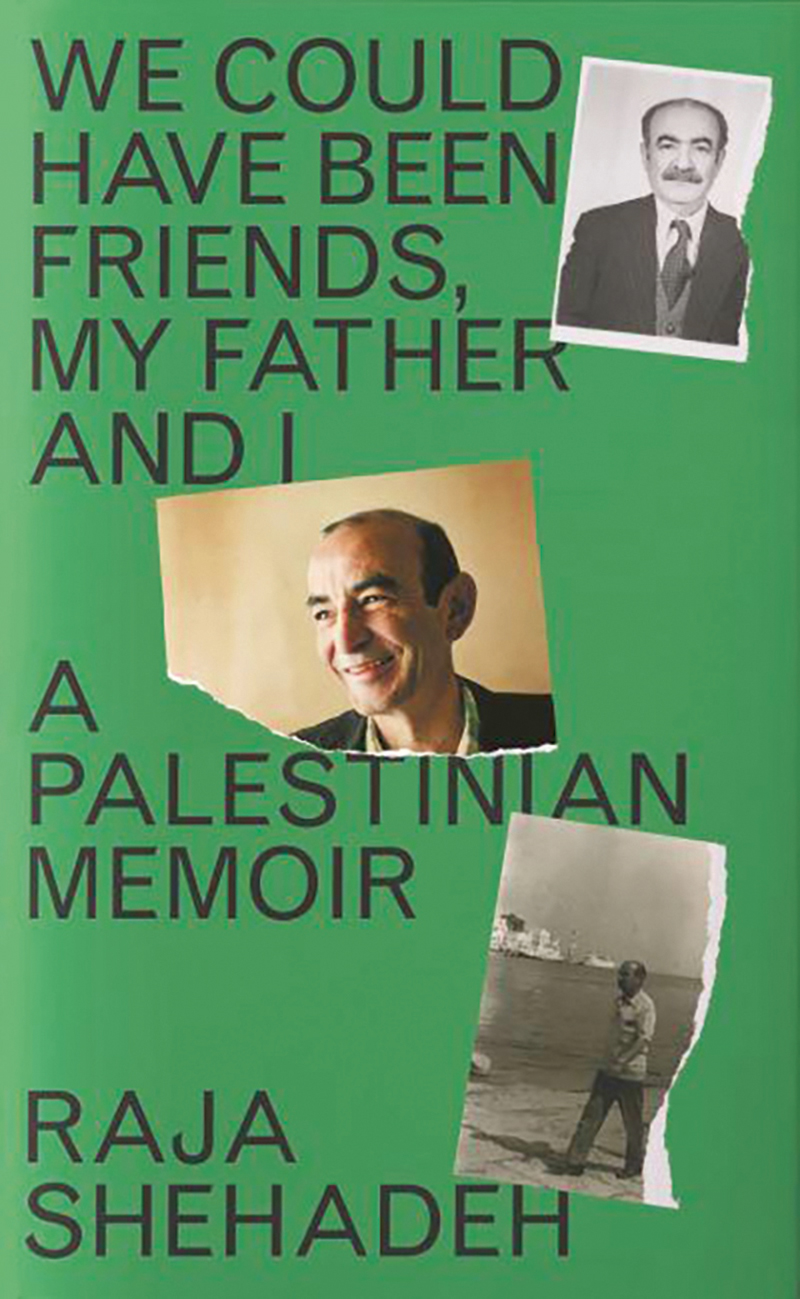

When the time came for finalising the cover for my book We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I, the designer chose a picture which showed my father with his arm affectionately over a young teenage boy. When I pointed out that the young man in the picture wasn’t me but my cousin, the designer asked for a similar picture with me intimately hugging my father. I searched the family photos; no such picture could be found. Sadly, I reflected on what I had lost in not drawing nearer to my father, who was a loving man.

Although my book has a lot to say about my father, Aziz Shehadeh, and his political and legal work, the book I wrote is not just a biography of him. It is an investigation of why we were not friends and why we could have been. During my father’s final year in 1985 I could see how busy he was putting his papers in order. I wondered whether he was preparing to write his memoirs, but it seems he didn’t have any intention of doing so. For many years all of those files remained in his house until I eventually moved them to my place.

It was during the Covid lockdown that I decided to open that cabinet. And when I did, I discovered a treasure trove. There I found documents and articles of his major legal cases and examples of his courage. File after file of neat, well-organised topics on his various political engagements and important cases were in there. During his lifetime my father endured many setbacks and accusations of treason for the bold political positions he took which often went against the prevailing trend.

Himself a refugee from the coastal city of Jaffa and living in Jordan, he worked diligently from 1949 to 1952 to implement UN General Assembly Security resolution 194 for the return of the Palestinian refugees to the homes they were forced out of during the Nakba of 1948. In 1954 he won a breakthrough case against the British Barclays Bank, forcing it to transfer to the Palestinian refugees funds in the bank’s branches in the cities that came under Israeli jurisdiction.

During his stay in London he was courageous enough to write a memo to British members of Parliament complaining about the torture of prisoners by the British head of the Jordanian army, John Bagot Glubb.

A few years later he was incarcerated in a Jordanian desert prison during the intolerable hot summer months for his political work in trying to advance democracy in Jordan. And yet for all his trailblazing legal and political work I could not admire him. Even though I later used law, just as he had done, against Israeli violations of human rights under occupation, we both failed to see the similarity between our two struggles.