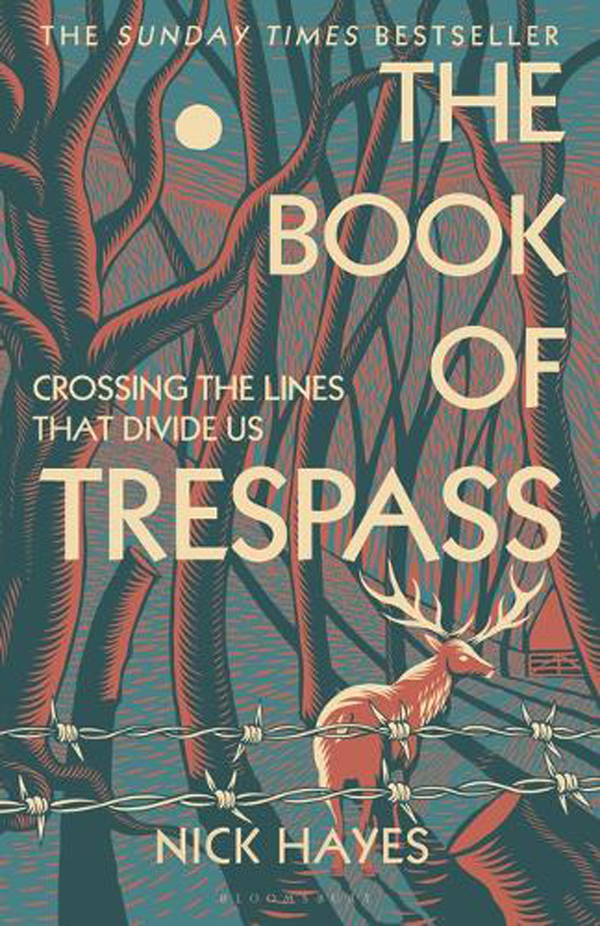

It’s been almost a year since The Book of Trespass was published, and the paperback version is due out in a week. Released into an entirely new context to when it was written, a world of lockdowns, limited exercise, a situation where people were finally rediscovering the paths and open country of their local neighbourhood, it caught a zeitgeist, a spirit that was alive but long dormant in English society – the idea that we should have greater access to our countryside.

The book takes the classic nature writing template as its structure – person walks through nature, describing what they see, giving historical context to the landscape. But in this case, every step it takes is on forbidden ground and, in one chapter, water. 92 per cent of our countryside and 97 per cent of rivers are out of bounds to the public, so finding places to trespass was not difficult.

The book takes the reader from the castle estates of dukes, through the farming estates of MPs and media magnates, describing the history of our exclusion from the landscape. It takes us to the real Downton Abbey, Highclere Castle, to the largest brick wall in England, built for the ancestors of current MP for South Dorset, MP Richard Drax, describing how new money entered the English countryside from slavery and colonisation of the West and East Indies.

The main aim of the book is to illustrate how societal divisions such as class, race and gender have been driven and intensified by the divisions imposed between communities and the land they once had access to.

Every trespass in the book was conducted in line with the Scottish outdoor access code, a code of responsibility towards the ecology and landowners of the area, written to accompany Scotland’s Land Reform Act of 2003, which opened up green space and blue space to the public. With a list of sensible exceptions, such as people’s back gardens, war monuments and MOD sites, the Scottish right to roam not only allows but encourages people to swim, paddle, camp and ramble through the beauty of its landscape.

England is surrounded by countries that encourage responsible public access, from Norway and Sweden to Finland and Estonia, and yet our nation – whose peculiar brand of private property includes the right to exclude all others, no matter how vast this property extends – remains stubbornly blind to the physical and mental health benefits of accessing nature.