As a teenager, Laurie Canciani suffered a brief, but crippling bout of agoraphobia. It is claustrophobia that afflicts Anna, the heroine of her debut novel, The Insomnia Museum, who is imprisoned in a council flat, but the effect is the much the same: it makes the outside alien; it magnifies and distorts whatever lies beyond her front door. Through long nights of wakefulness, she listens to noises – sirens, shouting, raindrops against metal – as they chime out the limited nature of her own existence.

Anna has not been allowed out since the day her mother tried to kill her; she lives with her disturbed father in a shapeless world, stripped of the only things that might give it structure: access to books and the ability to mark the passage of time. To keep her disorientated, he tells her there are 39 hours in a day. He swaps the cuckoo in their clock for the head of a Barbie-type doll. The mutant creature appears erratically, bashing itself off the sides of the window.

Like Eimear McBride, Canciano uses truncated sentences to create a sense of mental disintegration

The clock is one of many pieces of junk her father has picked up on forays through the estate; he spends much of his time fixing things that are not broken and the rest fixing himself with the kind of junk that is heated up on a spoon.

Later, when he has gone so “deep into the chase” he will never again be roused, Anna is taken in by a stranger, Lucky, a collector of human junk washed up on his shores. Lucky is trying to atone for past events, but his son despises his attempts to rescue lost souls. He thwarts his father’s do-gooding by selling drugs to those Lucky has just bailed out. “That’s me, winning,” he says.

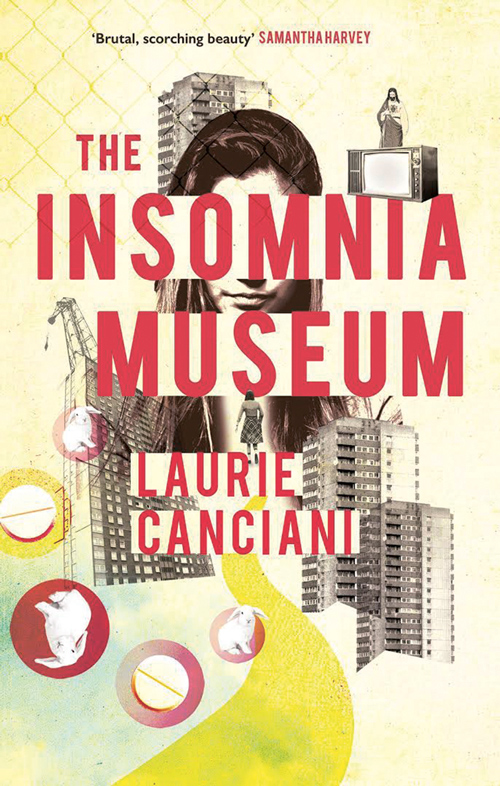

The Insomnia Museum is an ambitious exploration of loss, guilt and the way whole lives can turn on a single moment. Like Eimear McBride, Canciano uses truncated sentences to create a sense of mental disintegration, while the oddity of the museum pieces, like the plastic Jesus, who nods along uselessly in the midst of emotional turmoil, has echoes of Jenni Fagan’s The Panoptican.

For me, the drugs-related white rabbits imagery, which peaks in a clunky reference to the Jefferson Airplane hit, is too contrived. More successful is the Wizard of Oz theme; like Dorothy in the only movie Anna owns, she finds herself in a heightened landscape where Munchkins sell their wares on Sweet Street and Lollipop Lane. The question is: will she ever be able to click her heels and find herself a home?