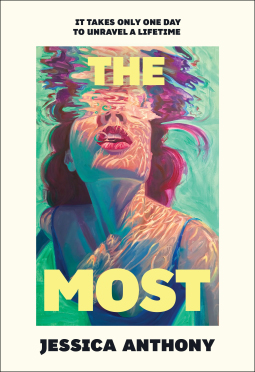

The Most is the fourth novel from Maine resident Jessica Anthony, described by literary giant Richard Russo as one of the most inventive writers working today. Witty, provocative, rich with insight and deep with melancholy, it features a ‘normal’ 1950s middle class American family with multiple cracks just below the surface. Though the tale might seem standard, Anthony throws enough unpredictable spokes in the wheel to keep us curious and committed until the end.

Kathleen Beckett is a mother of two who used to be a tennis champion but gave it all up to be a mother and housewife. Kathleen’s handsome husband Virgil is an insurance salesman, the kind who plays golf with the company partners, goes drinking with the in-crowd, and enjoys the lustful stares his good looks often elicit. He is not beyond having extramarital affairs but has the decency to call a halt when things advance to semi-seriousness, which he considers a sign of familial commitment.

Kathleen has so far been a success as a wife and mother, her organisational skills and ability to keep their house immaculate much appreciated. She admits she married Virgil “because he was easy” and because he was both risk and conflict averse (and thus the opposite of her own feuding parents). Family life simply slipped into place for both of them, based on a set of assumptions about what other people did and how women fitted into men’s work and play priorities.

- International Women’s Day: 50 feminist books to smash the patriarchy

- How letters from a 15th-century housewife unlock secrets of a forgotten England

- Monica Ali: ‘You have to have a core of self-belief to be a writer’

So when, one day in November 1957, Kathleen goes into the communal garden swimming pool and refuses to get out, Virgil is understandably concerned.

While Kathleen floats in the water, gazing up at a sky into which the Russians have just sent Sputnik 2, we are filled in on her backstory, the people and passions – as well as the tennis career – that she has given up for marriage. We learn about the family deaths she has endured, the childhood marked by acute loneliness, and the past love affairs she still has pangs for. We also learn about Virgil’s war experiences and his awkward relationship with his father.

It is not a new set-up: the bored housewife ripe for temptation; the dull, rigid, unseeing husband. Indeed, there are shades of Anne Tyler’s Ladder of Years, in which a dissatisfied housewife suddenly walks out on her family. Both consider what happens when well-behaved middle-aged women suddenly ache to test new waters, ones not pre-approved by their husbands or children.