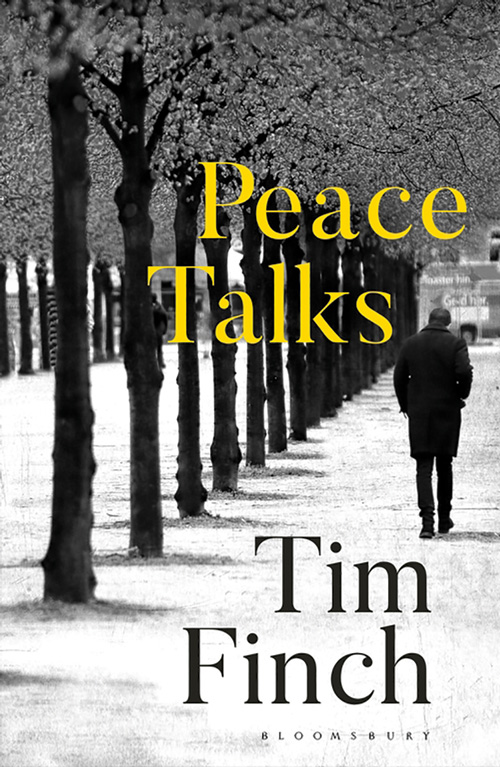

In his first, well received, satirical novel The House of Journalists, campaigner/reporter Tim Finch exploited his intimate knowledge of the refugee experience to create an insider’s fiction more illuminating than his any of his justly admired factual accounts. I don’t know if he spent his years garnering plaudits for his work as director of the Refugee Council and senior political journalist at the BBC secretly nurturing a literary desire, but I’m grateful he found the time. Many contemporary British news journalists have ventured into novel territory, but while I enjoyed Kirsty Wark’s The House by the Loch and acknowledge that Frank Gardner’s is thrillers are best sellers, Finch has channeled his understanding of current affairs into fiction more successfully than most. With his second novel, Peace Talks, he has surpassed the achievement of his excellent debut to create something insightful, emotionally resonant and unexpectedly poetic.

At the centre of Peace Talks is Edvard Behrens, a highly respected diplomat who specialises in international peace negotiations. He has been sent to a hotel in the Tyrol to arbitrate a deal between two warring Middle Eastern factions and fills his day easing them masterfully towards an agreement, while his evenings are spent making small talk with colleagues and devouring his balcony view of ‘rooftops, snowfields, forest and mountains, twilit by a sky that is a deepening blue and orange bruise.’

Peace Talks is full of terrible details of brutality in battle, in love and in death. Yet it is consistently a pleasure to read

The engagingly informal prose – his account is a one-sided conversation with his wife Anna – slips smoothly from matter-of-fact descriptions of wartime atrocities to tender reminiscences of his time with the absent Anna. The infantile pettiness which characterises his tippy-toed mediation meetings is often very funny (there is a hint of Monty Python and Chris Morris in the points-scoring squabbles over the angles of the window blinds); that it doesn’t jar with what increasingly becomes a profound meditation on memory, loss, and the agony of grief is a mark of Finch’s management of tone.

The novel is full of terrible details of brutality in battle, in love and in death. Yet it is consistently a pleasure to read. And unusually and best of all, it doesn’t blow it in the denouement. It never over-explains, or exhausts its own metaphors, or enforces a false sense of closure. In fact the final few pages are a brilliant coincidental summation of the shock and adapt reality we’re living in right now. We could all do with reading it.

French writer Annie Ernaux is equally compelled by memory, having virtually created a genre in her mixture of mind/body memoir and story-telling (it sounds obvious now, but Ernaux was mastering this approach decades before Eimear McBride or Sinéad Gleeson came along). A Girl’s Life sees her return to a formative teenage summer, when she lost her virginity in a rather commonplace experience shared by millions of teenage girls who, like her, are likely to have avoided its recollection ever since. Ernaux finally turns to face it – the embarrassment of her naive trust in an older men, her eager capitulation to him, and her shock in being suddenly casually supplanted.