And my father had fought in the war, so I had to get to know him when he came back.” Books, or at least the three the Waterstone family home held under its roof, were there to absorb his loneliness – and to suggest a life bigger and better.

You never forget your first love, goes the old adage, but rarely does your first love make you your fortune. And yet, after spells working for a broking firm in Calcutta, India, then as marketing manager for the now-gone Allied Breweries, then WHSmith (he was sacked, he was delighted; “They were right to fire me, now I can do what I want to do!”), in 1982, at the age of 42, he emptied his bank account and launched Waterstones with a view to bringing a quality bookshop to every town.

“I wrote a business plan,” he remembers, “and I remember saying in it that within 10 years we’d be the biggest booksellers in Europe. It was a ridiculous thing to say, but I knew we could do it. I knew what we were doing was right.”

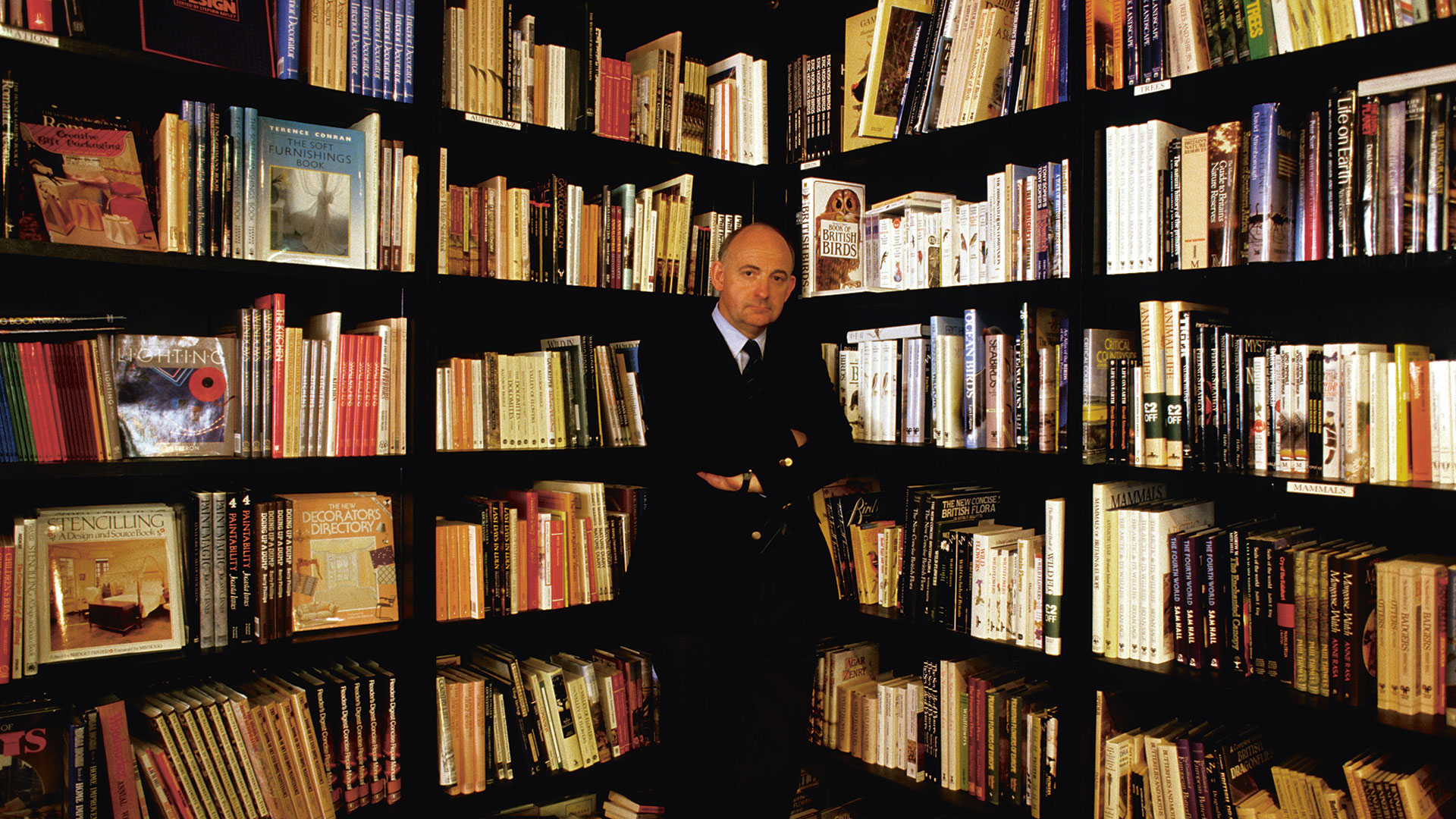

The vision was “big shops, absolutely packed with books, open for hours and hours, seven days a week and staffed with young staff who loved books, who really knew what they were on about.” The first store would be at Old Brompton Road in Kensington in West London, which remains to this day.

Once he’d reached “five or six stores”, with help from his own staff, many of whom invested their own money in their boss’s vision, the big investment started to come. “And then it never really stopped,” he says. Plenty of people launch businesses on loves and obsessions – there’s a nail salon filled with broken dreams in every town in Britain. There must be more to it than just loving books? “Not really,” he says. “We just knew what people wanted. When we started the business bookselling had been awful for a long time.”

Now 79, his eighth decade looming, Waterstone’s breathless love of books is still at the forefront of every utterance today. He describes launching the business as the greatest fun he’s ever had. That the success of the chain “proved the cultural health of the country”. He says: “Bookshops are fantastic places for the community to enjoy.”

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Just last Saturday he popped into Waterstones’ Piccadilly branch in central London. It’s Europe’s largest bookstore, with more than eight miles of shelving spread over six floors. There he sat, in one of the shop’s large comfy armchairs, unannounced, watching the crowds. “I can’t even explain the pleasure I felt watching people browse. But people love what we do. We’re extremely lucky to have such a large share of the market, but we have it because we do what we do really, really well.”

Tangentially, we discuss the state of record shops in 2019. Waterstone reluctantly expresses a view that he believes music retail is “completely doomed”. Fuel for the fire for those who believe HMV’s failing began when its record shops started to feel more like gadget emporiums (the company bought Waterstones in 1998 before eventually selling in 2011; Waterstone was founder chairman of the ill-fated alliance between 1998 and 2001, and says he hated going into branches of the store during this time). The central tenet to his business philosophy remains “Make it good”.

Loads of children, librarians working hard, an exuberantly happy place,

Asked about libraries and their importance to communities and the cultural health of those who live around them, and he tells a story about recently waiting for his daughter in a library in Kilburn, North London. “It was a cracking place, it really was,” he gushes. “Loads of children, librarians working hard, an exuberantly happy place.” He won’t take the easy shot of blaming Tory cuts for their failing. “I want libraries to survive,” he says. “But I want them to be as good as the library I was in when I was in Kilburn.”

He’s worried about the high street, though feels some comfort that landlords are now having to reassess their rents. He’s confident that Waterstones will exist. He’s not so sure about the high street itself. He’s less concerned about Amazon. To an extent, he can see how the two brands complement each other. “We have exactly the same market share now,” he says. “We’re the two dominant brands.

But here’s the thing, I believe the nature of book buying, online and in person, are completely different. If you know what you want, you’re going to go to Amazon. I do it myself numerous times a year! But we all know online can’t replicate the same feelings of pleasure you get in a great bookshop. Our research tells us that well over 70 per cent of purchases at Waterstones were bought on impulse. Even when people had come in to buy a book, they’d left with five more they hadn’t intended on buying when they came in.”

Waterstone hopes one impulse purchase that might be plucked from the shelves of his empire might be his memoir, released this month, entitled The Face Pressed Against A Window. “I think when you’re approaching 80, most of the battles you’re going to face in your life are behind you and it’s a good time to take stock,” he says.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

And yet, as well as being an unflinching account of his life from childhood to the present day – taking in a failed marriage, as well as a brief stay in a psychiatric unit – the book also features his first published fiction, in the form of two short stories contained within the book’s appendix, since the publication of his fourth novel, In For a Penny, In For A Pound in 2010. “Hemingway once said that fiction told more truth than most people’s truth,” he says, in explanation. “I’m still learning new ways to write, books are still teaching me things even now.”

The Face Pressed Against A Window is out now (Atlantic Books, £17.99)

Interview by James McMahon | @jamesjammcmahon