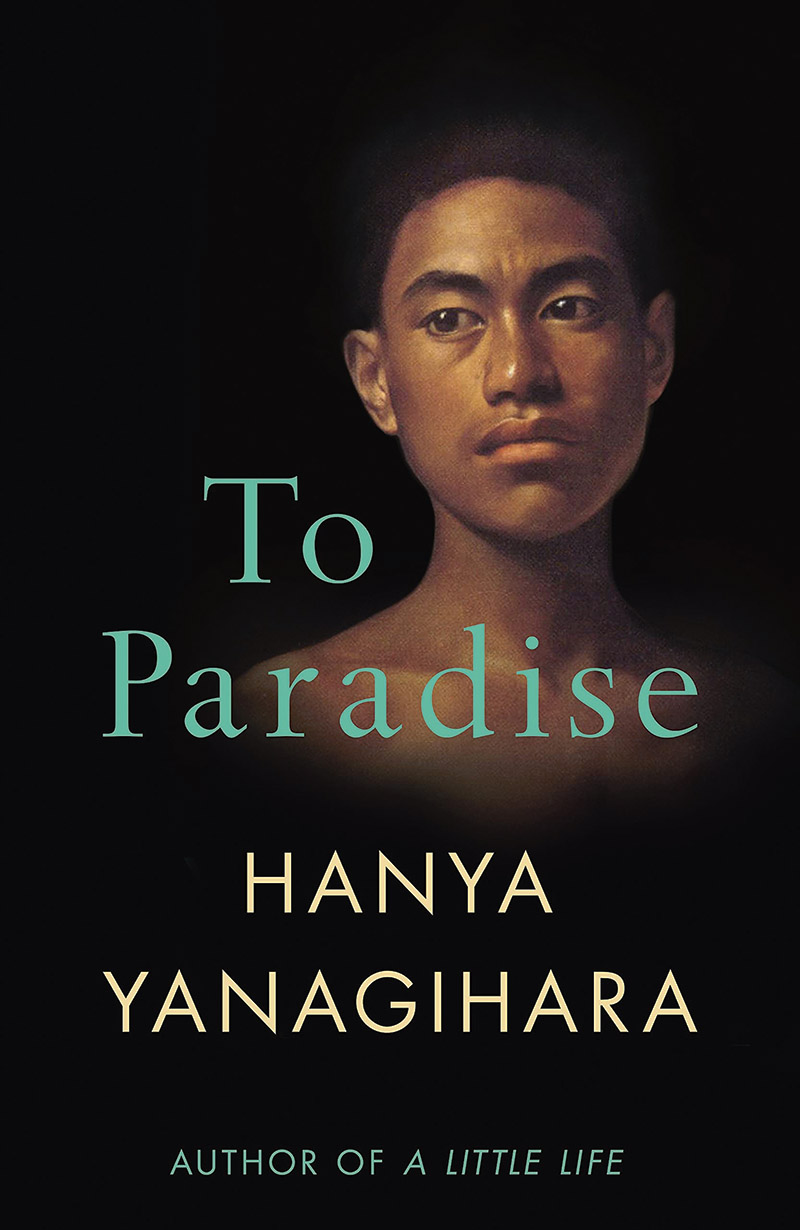

This month sees the long-awaited publication of literary sensation Hanya ‘A Little Life’ Yanagihara’s new novel, To Paradise. There is not room here to summarise the many issues this ambitious novel covers in its 700 pages. Suffice to say, throughout the two centuries it spans, starting in a fin-de-siècle 1890s New York and ending in a totalitarian, climate-ravaged future, it poses fascinating ‘what if’ questions about sexuality, race and government responses to existential threats. What stays longest for the reader though, is the elegant, evocative writing with which Yanagihara tells her emotionally powerful stories.

We read of fragile temperaments and broken bodies, the corrupting stench of wealth and unearned privilege

Interesting territory is opened up in all three of the ‘books’ which make up the novel. In Book One, ‘Washington Square,’ (a reference to a popular early Henry James novel), we are introduced to a 19th century New York in which same sex relationships are commonplace and uncontroversial.

Bearing in mind how deeply the world described by obvious influences Henry James and Edith Wharton relies on uncontested, oppressive gender-based rules, how are ranks & hierarchies arranged in this alternative universe? A fun parlour game; imagine Pride & Prejudice if Mr. Bennett was taxed with marrying off his sons to the sons of rich families.

Yanagihara’s conclusion is that freedom regarding gender does not guarantee a more liberated society for either sex. Oppression based on racial prejudice, class division, and rigid, myopic family rules remain. She suggests that human beings tend towards imposing judgment, control and power imbalances regardless of contemporary social trends. In short, life is always made difficult for someone.

This idea is threaded through all three books, into Aids-blighted 1990s Manhattan and a dystopian future characterised by fear of disease, climate catastrophe and state control.

A Little Life divided readers into two camps: those deeply affected by a tragic tale of trauma and abuse, and those who felt cynically manipulated by a grim and unrelenting fictional misery memoir. To Paradise is altogether a more gentle read and may prove more palatable for Yanagihara naysayers. Its most profound ‘what ifs’ are those involving its authentically portrayed relationships, some joyful, some agonisingly dysfunctional. These tend to be between either gay male lovers or young men and fathers or grandparents fraught with regret over their mishandling of fragile childhood moments.