The very first words spoken in the television series Adolescence take the form of a voice note sent to detective inspector Luke Bascombe (Ashley Walters) from his son, Adam (Amari Bacchus), asking to stay home from school because of a stomach ache. Luke listens to the message, not buying Adam’s malingering for a second. Then he gets into his unmarked police car and, seemingly oblivious to the link, begins to complain to his sergeant about his own stomach problems, which are the result, he says, of his wife telling him to substitute eating apples for smoking cigarettes.

It’s an effective opening scene: in very little dialogue, we learn plenty about Luke as a husband and father, while the quiet domesticity and humour contrast with the crescendo of the police raid that is about to take place. The scene also hints at how adept men are at creating narratives in which they are victims rather than being responsible for their circumstances. But more than that, it sets up the idea that one male’s behaviour can often mirror that of another, using Adam and Luke to foreshadow the show’s central father-son relationship between Jamie and Eddie.

Get the latest news and insight into how the Big Issue magazine is made by signing up for the Inside Big Issue newsletter

In doing so, the show subtly asks viewers to compare males that society might deem ‘monstrous’ with those considered ‘good’.

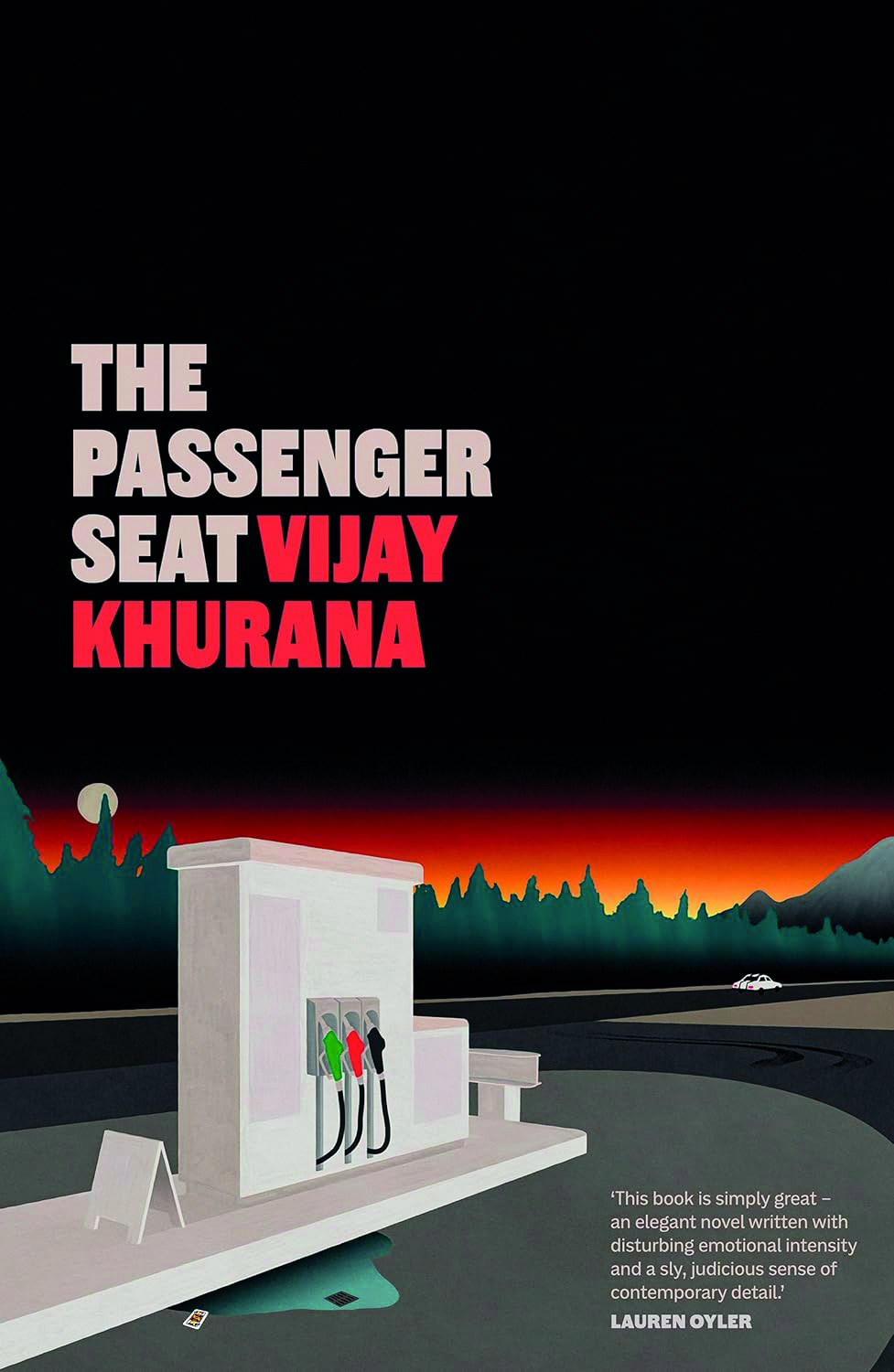

This question of depicting ‘good’ and ‘bad’ men in fiction is something I have been interested in since I began writing my first novel, The Passenger Seat. The book explores the connections between male friendship and violence through the story of two teenagers, Teddy and Adam, who commit several acts of violence while on a road trip together. It also portrays a friendship between two older and better- adjusted men, inviting the reader to see similarities in these seemingly very different relationships. Just like the violent teenagers, the older men also create narratives in which they are not responsible for their actions, while performing their masculinity in ways that affect how they treat those around them, especially women.

One of the things that drove me to write the novel was the experience of reading various news reports in which male violence was labelled as “incomprehensible”, as though there could be nothing to learn from a closer examination of it, let alone of the men who commit it. This strikes me as an ultimately unproductive response, especially given how often such violence occurs. To label something as incomprehensible is to absolve ourselves of the responsibility of trying to comprehend it. It may be comforting to think that dangerous and harmful men are nothing like the rest of us; it is harder to ask ourselves about the ways in which they are.