Kimberly Campanello’s work has always been uniquely difficult to define. Her most significant work, MOTHERBABYHOME, was a 796-page “poetry object” that took the form of a report on Ireland’s infamous Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, where up to 800 children had died between the 1920s and 1960s.

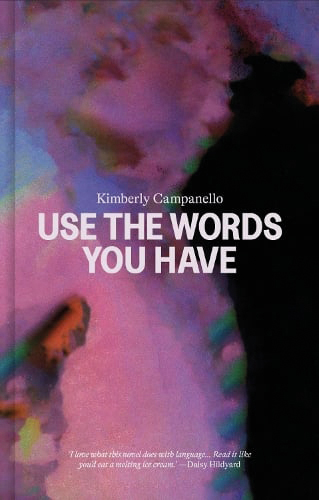

There are only six copies of the original edition, each poem printed on vellum and stored in an oak box. Hence, the term “poetry object”. Her practice moves fluidly between poetry, visual art, durational performance and digital literature, defying any easy categorisation. Knowing this, it feels uniquely perverse that Campanello’s latest project, Use the Words You Have, comes to us in the form of a novel.

Campanello brings many of her poetic sensibilities with her in her transition to prose. The paragraphs are independent, spaced apart. There’s plenty of room on every page for the words to breathe. The perspectives often shift. You ask yourself: who is telling this story exactly? Is this a slyly disguised memoir? The setting is alienating. An American exchange student is packed off to Brittany for the summer. She is not nameless but is only ever referred to as “K”. She falls for a local boy, called “M”.

As part of the exchange programme, K is forbidden from speaking English under any circumstances. Even use of a dictionary is heavily discouraged. If she doesn’t know the word for something, she must use the words she has. The romance that sparks between K and M is a slow burn, but nothing moves fast in that lethargic Breton heat.

Campanello owes a great deal to writers such as Rachel Cusk and Deborah Levy. The alienation of Cusk’s Outline and the humid atmosphere of Levy’s Hot Milk are natural comparisons. But Campanello’s novel holds its own alongside those works.

There are entire sections where nothing much happens; just descriptions of basic tasks, perhaps a mention of the sea, maybe someone is eating a peach, and yet Campanello’s words will utterly captivate you. She has a way of seeing the world in a way that only a poet can see, a way of producing a novel that only she can produce.