Even though officially Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay were the first men to summit Everest in May 1953, George Mallory is just as famous, and the mystery remains as to whether he beat them to the top. Like James Dean, Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix or his own hero, the poet Percy Shelley, Mallory is one of the good who died young, like all those dead soldiers from WWI, destined to ‘never grow old’.

I’ve been fascinated by his story for many years, and the mythology that grew up around him after his mysterious death a century ago in 1924. I’ve written several other climbing books and made mountaineering documentaries for the BBC but there’s no other character quite so compelling.

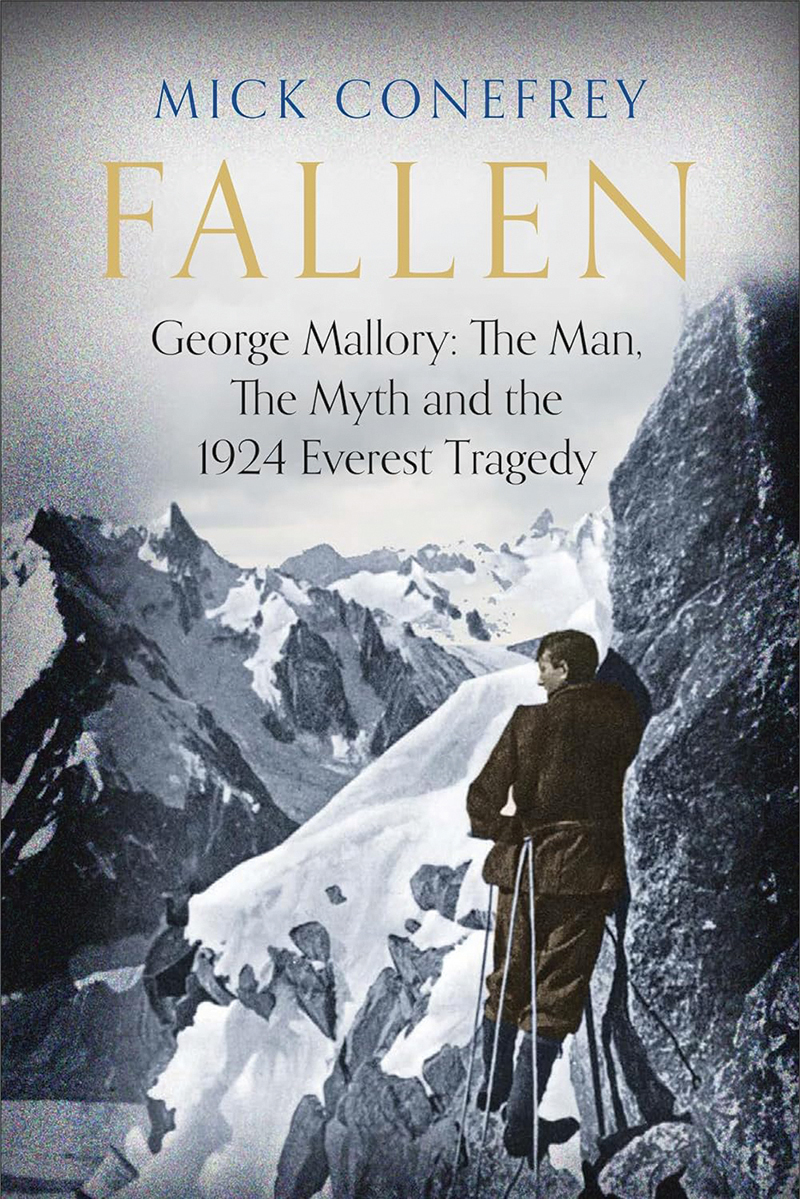

Mallory had star quality in bucketloads. He was handsome and charismatic, a brilliant climber and skilled speaker. His name was his destiny: ‘George’, the dragon slayer, ‘Mallory’, echoing Thomas Malory, the first chronicler of the Arthurian legend. Mallory was the beating heart of three British expeditions, the climber who kept going when everyone else wanted to turn back.

Get the latest news and insight into how the Big Issue magazine is made by signing up for the Inside Big Issue newsletter

But was he an obsessive egotist driven by ‘summit fever’, or as his team-mate Edward Norton wrote: ‘the most formidable opponent that Everest has or is ever likely to encounter’?

In many ways, Mallory was a typical middle-class British mountaineer. A vicar’s son, he learned to climb at public school, and practised in the Alps and North Wales. But there was much more to him than that. His friends were artistic and unconventional: Duncan Grant the painter, Lytton Strachey the historian, John Maynard Keynes the economist, Rupert Brooke the poet. In his famous essay The Mountaineer as Artist, Mallory compared a climb in the Alps to a great symphony with all its highs and lows. For the 1922 official Everest account, he penned one of the most lyrical descriptions of Everest ever written, describing it as a “prodigious white fang excrescent from the jaw of the earth”. In 1923 he told a journalist that he was willing to risk his life for Everest, “because it is there”.