I always knew that my book about death was going to be a book about life. But it took a storm on All Souls’ Day to teach me that it was really a book about love.

It was November 2, 2019. I was in Devon to attend a ritual at the Sharpham Meadow Natural Burial Ground. People who have loved ones buried there were to gather after nightfall, high on the hill. A candle would be lit on every grave, the names of the dead read out, spoken into the wind and dark. The widowed, the unmothered, the unmoored and left-behind – each would place a pine cone on the bonfire.

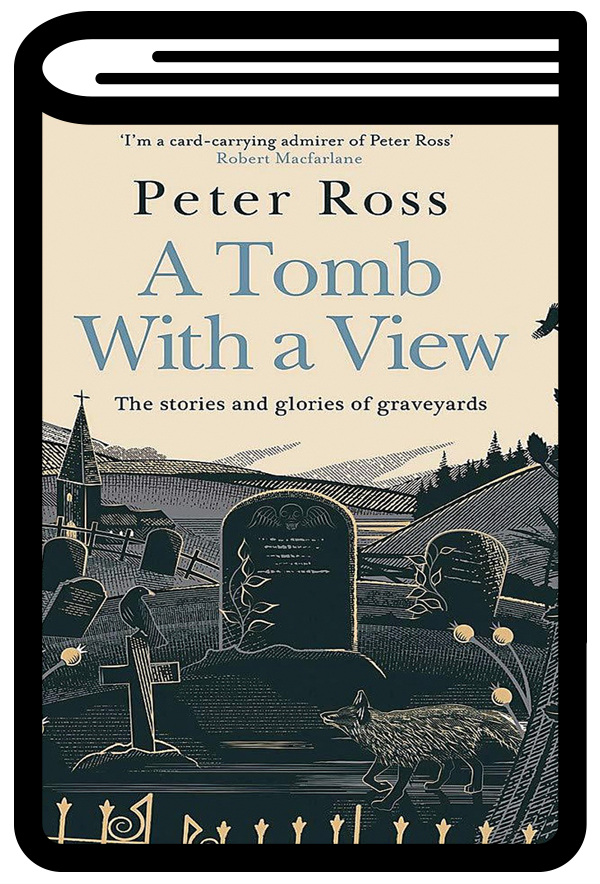

The cones are coated in copper sulphate; placed in flames, they flare green and blue, and, as they do so, stories are told of those who had been lost. It would, I thought, be a dramatic and moving climax to the book I was writing: A Tomb With A View: The Stories & Glories of Graveyards.

But this was England in winter. The wind got up and rain came down. Flood water rose, trees fell, roads were closed, the ritual was cancelled. It seemed a shame, though, not to mark All Souls’. It is a day when the lines between life and death are blurred, when one might push a tentative hand right through the mirror and touch yearning fingers on the other side.

So, I arranged to meet Bridgitt at the meadow. She wanted to visit her husband’s grave, which she does often, and would be glad to sit for a while in the last of the light. Wayne had taken his own life the year before at the age of 45. Sitting with Bridgitt while the storm howled was one of the privileges of my life. What she was telling me, I realised, was a love story. It was about grief and pain, of course, but those emotions were borne from the intensity of the love she and Wayne had for one another – and which she has still. “You’re not only in my mind,” she had addressed her husband as he lay beneath a felt shroud, awaiting burial. “You’re in my blood, you’re in my bones, you’re everywhere. You’re in your children, you’re with us, you’re here.”

I spent a year travelling around cemeteries and churchyards in the UK, Ireland and beyond

This connection between the living and the dead is at the heart of my book. In preparing to write, I spent a year travelling around cemeteries and churchyards in the UK, Ireland and beyond. I attended four funerals and a wedding. In Belgium, I was present for the burial – with full military honours – of two British soldiers who had died on the western front in 1915 and whose bodies had recently been discovered during an archaeological dig. En route back to France from the ceremony, travelling with officials from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, we stopped at a building site where, that morning, four further skeletons had been found. To gaze upon those skulls was, again, a privilege. These men – these boys – had gone off to fight in the Great War and had not returned. They were among the huge numbers of missing with no known grave. Now, more than a century after their deaths in the trenches, I had the honour of witnessing their return to the light, and the task of trying to write about it in a way that did justice to the solemnity of their sacrifice and the miracle of their resurrection.