We understand that race and racism exist, we understand that not all sex is fun sex, but in the utopian world of Bridgerton we get to suspend our disbelief at the perennially cute world and just enjoy it. We get to say, darn it, I know the state of the world is shit, but I’ll worry about that after these six

episodes are over.

Of course, the state of the world wasn’t and isn’t this cute. The reasons there were around 50,000 people of colour in England by the mid-1800s weren’t pretty at all.

I’d been besotted with the Regency genre ever since I began my own love affair with the witty, at times laugh-out-loud, world of Georgette Heyer when I was a teenager.

When I was 14, I found a battered copy of The Talisman Ring hiding among the Sidney Sheldons and Jeffrey Archers in a secondhand bookstall in the foothills of the Himalayas.

But it took Shonda Rhimes’s take on the Bridgertons’ world to make me ask the question: were there people of colour in England in Regency times?

The answer, apparently, is a resounding yes. There were mixed-race children of the East India Company earls and their Indian wives and mistresses. There were nannies from the Caribbean and lascars from the sub-continent.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

There were people displaced because of the complex web woven by histories of colonialism and slavery. Those were the real histories of the 18th and 19th centuries.

But Bridgerton and then its spin-off series Queen Charlotte open the door for the rest of us authors to indulge our love of the Regency world with all its charm and lols and high jinks.

We can now, finally, dive deep into period dramas that allow us to explore real histories that don’t gloss over colonialism and slavery and the rampant greed of the colonial trading companies.

If Bridgerton doesn’t quite go deep enough, it yet allows us to do so. It allows us to read historians like William Dalrymple and Richard Gott with a new appreciation for the complexity of those times.

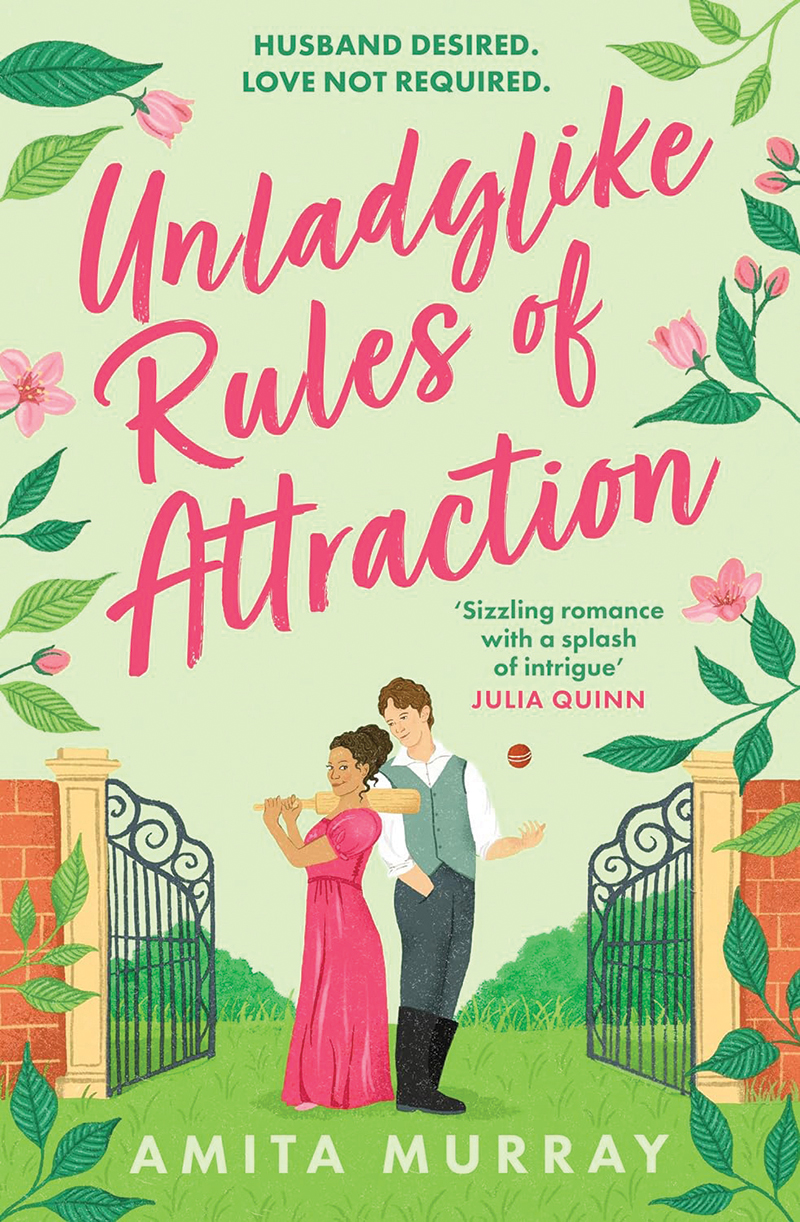

In my series of Unladylike Regency novels, I not only focus on the mixed-race Marleigh sisters, daughters of an English earl and his Indian mistress, displaced to England when they were children, but I also get to reimagine the rat baiting pits and the pleasure gardens and the streets of London populated with all manner of people from tavern owners and street sellers and lascars and nannies.

In Unladylike Rules of Attraction I get to write the most swoonworthy of things: a woman who wears Regency dress but sits on the haloed floors of Queen Charlotte’s court and plays the sitar. Who falls for a man who his relatives charmingly call the urchin thief from Jamaica.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

I get to reinvent the rules of historical romance and decide that it can be funny and cute and real at the same time. Most of all, I get to write heroines who are strong women of colour and who get to have a whole lot of fun in the bedroom.

In the meantime, we need wait no longer. It’s time to get our feathers and hartshorn ready, viewers, because here comes Bridgerton season three. All fingers crossed for our very own Penny.

Bridgerton season three is on Netflix from 16 May.

Unladylike Rules of Attraction by Amita Murray is out 23 May (HarperCollins, £8.99). You can buy it from The Big Issue shop on Bookshop.org, which helps to support The Big Issue and independent bookshops.

This article is taken from The Big Issue magazine, which exists to give homeless, long-term unemployed and marginalised people the opportunity to earn an income.

To support our work buy a copy! If you cannot reach your local vendor, you can still click HERE to subscribe to The Big Issue today or give a gift subscription to a friend or family member.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty