I’m not sure when my obsession with old images started, and what it is about them that I find so alluring. After university I lived for several years in Berlin and would spend each Sunday at flea markets digging in shoeboxes full of old photographs. There’d be no rhyme or reason to the selection found in any one box, a wild mix of subjects – family snapshots, formal portraits, postcards, clippings – so many fragments of stories and hints at lives now lost.

I’d make a selection from each box I’d trawl, to create a cluster of images that in some way spoke to each other, spun some other kind of story. It was around this time that I got into making collages, and discovered various online archives of public domain images that were starting to emerge. I became obsessed with these seemingly endless portals, trawling through them for hours every day. Glued to my screen, it wasn’t perhaps as healthy as a Sunday stroll around a market, but in terms of visual variety it was so much more expansive. In a way these archives were like the ultimate shoebox – largely unsorted, unfiltered, spanning hundreds of years, multiple genres.

I bought a cheap printer for my collages, but most I squirrelled away into computer folders, sorting them into themes, associative categories, and by more unexpected connective traits. When I started doing the same for books, audio and film the idea for The Public Domain Review website was born, a kind of web-based wunderkammer dedicated to exploring and celebrating out-of-copyright works found in online archives.

Ten years later at the start of lockdown, my thoughts turned to creating a book. The site has collections in a variety of media, books, film and audio, but when it came to thinking of a book, it was images I turned to.

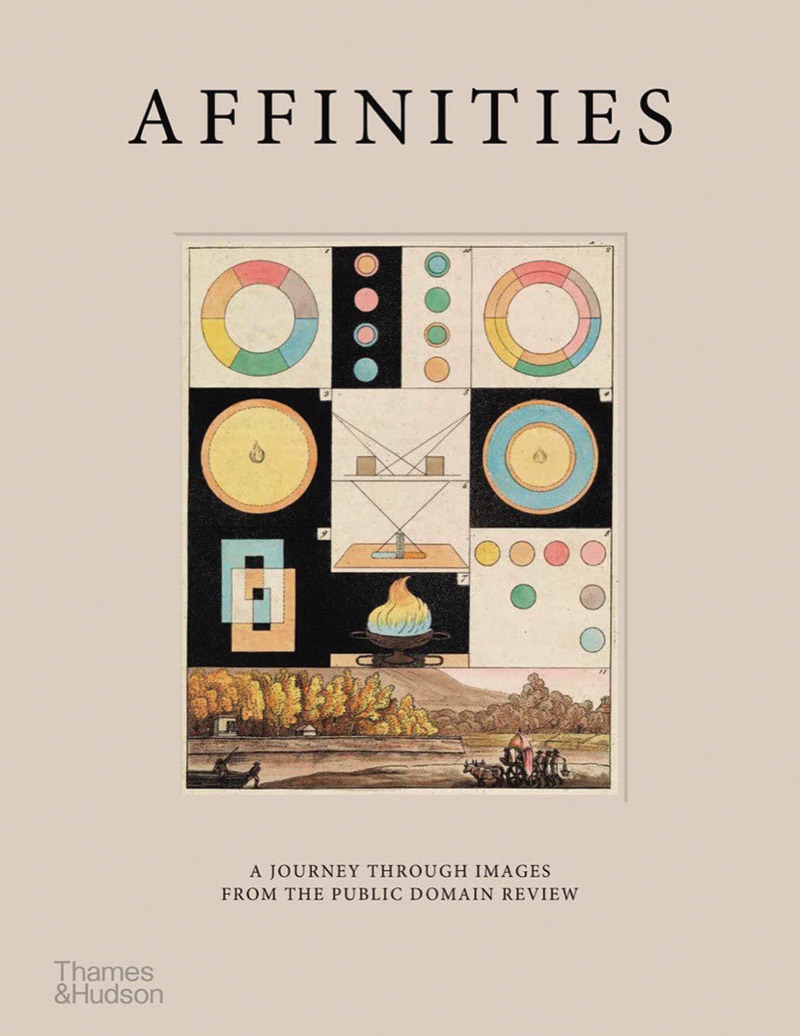

They were the project’s genesis and, in many ways, its beating heart. I also knew I wanted the book to be an exploration of how images can speak to one another, as well as to us. What new worlds, new forms of knowledge could be spun by placing different images next to each other? It also felt appropriate to mark the 10-year milestone, not with something retrospective, but to create something new. That’s what The Public Domain Review has always been about – not just highlighting historical works, but encouraging readers to explore the creative potential in this incredible resource. So a big book of public domain images felt like the perfect vehicle to celebrate the project and Affinities was born. As with The Public Domain Review, the book has been assembled from a vast array of sources: from manuscripts to museum catalogues, ship logs to primers on Victorian magic. There’s lots of favourites from the site in there: a 17th-century gouache of a female pict warrior in floral tattoo, Wilson Bentley’s photos of snowflakes through a microscope, Japanese wave and ripple designs. But across the pages of the book they’ve been cast into this new imaginative space.

Why this title Affinities? All the images in the book are ones with which I have, and hope readers will do too, a certain affinity. To return to the flea market, they are the ones I’d for certain pull from the shoebox, images that elicit some kind of attractive spark that puts a halt to the scrolling, that make you pause, look closer. It’s here we touch on the first sense of the book’s title, how individual images speak to us.