Creative projects can help us see familiar places with a fresh perspective. A drawing, a painting, a film or a book about a place can change the way we look at it.

That was one of the thoughts I had in mind when I started mapping out Scotland by hand in the summer of 2020. I wanted the process of drawing out the country in detail to tell me something new about the place I have lived in for most of my life.

In my work as an artist and writer I often aim to make Scottish history and culture more accessible to a wider audience. In the past I have written about specific moments and artefacts from Scotland’s history, but for my next project I knew I wanted to try something which gave a more expansive overview of the whole of Scotland, something which would try to encapsulate the story of the land, as well as the local histories of our towns and cities. It was then that I started thinking about making an atlas of Scotland, using hand-drawn maps as a basis for telling those stories. Admittedly the idea was quite daunting at first. It was the biggest creative challenge I had ever set myself.

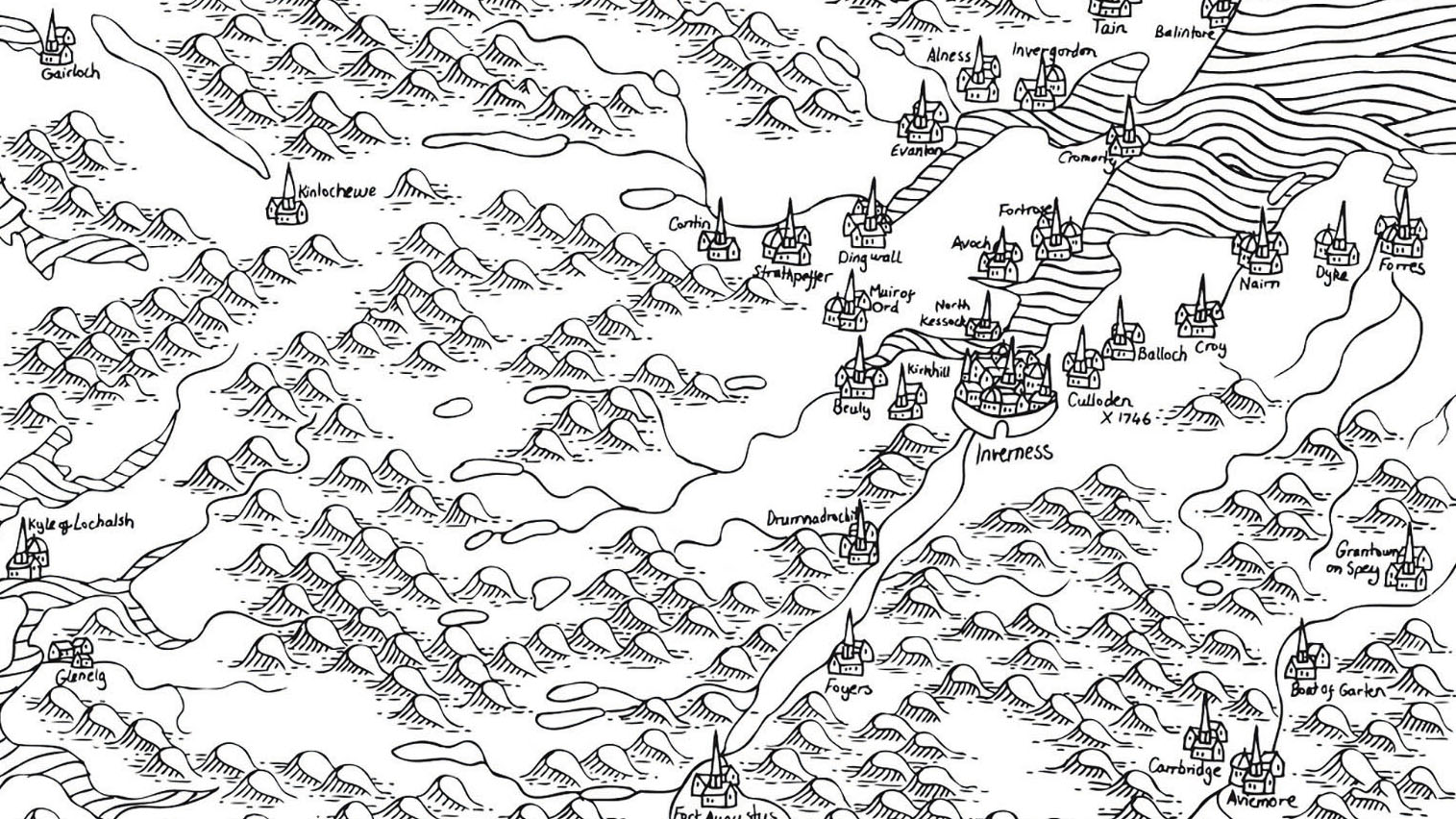

I got started on Atlas of Scotland during the first lockdown. A lot of my time was spent at a drawing board I set up in my bedroom, slowly ticking off the list of 37 maps I had set myself to complete. Over many months a picture of Scotland started to emerge in segments, and I began to see how it would all work laid out in the pages of a book. It also made me reconsider the vastness of Scotland, which is sometimes thought of as a ‘small’ country. Drawing it all out by hand, I could see how expansive and how diverse the land really was, and how much potential it had for the future.

The Atlas covers some of what is already widely known about Scotland and its history, but it also deliberately seeks out the unusual, the forgotten or the overlooked. Those are the parts I thought would be most enjoyable for readers. I wanted it to be a kind of treasure trove of discovery, and challenge peoples’ perceptions. There is something of historical significance to be found in every corner of Scotland, so one of the challenges was deciding where to stop. The amount of detail you could delve into for every place was arguably unlimited. The challenge was to try and create an all-encompassing depiction of the country, and to cover as much of it as I could, while also keeping the project manageable.

The first aspect of Scotland’s history that I highlight in the Atlas of Scotland is its physical geology. The stones of Scotland, forged in deep time, offer some of the most remarkable insights into the ancient composition of the world. The Great Glen, which cuts straight through Scotland from sea to sea and contains Loch Ness, is Scotland’s deepest and most prominent fault line. But the fault doesn’t end there; it bends northward, cutting through Shetland and southward, through the north of Ireland. Remarkably, the very same line also cuts through Newfoundland, Canada, thousands of miles to the west. Scotland’s mountainous Highlands were once connected to the same Caledonian range which now form the Appalachians in North America, as well as the mountains of Sweden and Norway.