There’s a splendidly awkward scene in Happy End, the new film from Austrian director Michael Haneke. We’re among the refined elegance of the dining room of the Laurents, an affluent family that own a transport business in Calais. Thirteen-year-old Eve has just joined the household, now that her mother is gravely ill in hospital with what is euphemistically termed a bad case of poisoning but everyone really suspects to be a suicide attempt.

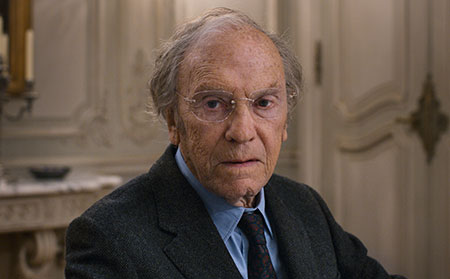

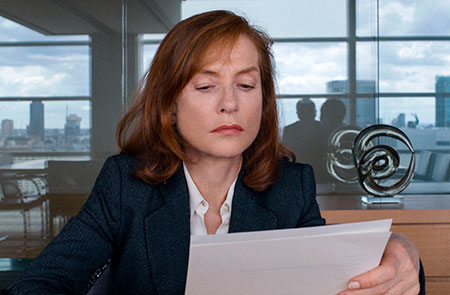

Her estranged father Thomas has remarried but is seeing other women behind his young new wife’s back. Thomas’ sister Anne is struggling to save the family business from a potential criminal injury lawsuit caused by the tragic incompetence of her son Pierre, an unstable alcoholic. And presiding over this is Georges, a despairing octogenarian who longs for death and whose frequent memory lapses suggest the onset of something more serious. To the sound of cutlery scraping against antique porcelain like the squeak of rusty gates in a cemetery, Georges quizzes this new arrival to his family. Having ascertained enough to sate his interest, he says to Eve: “Welcome to the club”.

This ghoulishly mordant moment might also serve as our reintroduction to the world of Michael Haneke. Not only does Happy End see the veteran director work with actors he’s used before – notably Isabelle Huppert, who plays Anne, and Jean-Louis Trintignant as Georges – but the film worries away at themes that recur across his work: suicide, bourgeois hypocrisy, European racism, the alienating impact of new technologies, the violence that lurks within a seemingly stable family unit. Happy End is not without a dark and peppery wit. But, despite its title, this is not a film that leaves you aglow with optimism and high regard for humanity as its credits roll.

Instead Happy End exposes the fault lines and tensions across the Laurent generations to Haneke’s clinical and remorseless scrutiny. As with so many portraits of family dysfunction there’s a sense of unease here, one that Haneke amplifies brilliantly. It is a collection of disquieting fragments, discordant snapshots that create a mood of unsettling menace, of impending catastrophe.

Despite its title, this is not a film that leaves you aglow with optimism and high regard for humanity as its credits roll.

What exactly is the unheard question Georges, now confined to a wheelchair, puts to a group of young migrants on a street in Calais? Who is sending suggestive messages to an unknown recipient via a social media account that Haneke occasionally cuts to? Why is Anne’s son Pierre attacked by a man outside a block of flats in the city centre (and later seen performing weirdly athletic karaoke)? The film builds its narrative by planting in our head these questions, and more: it involves us in a game of darkening speculation, of raising fears that its brilliantly bleak final scene does little to assuage.