Moving to London after university in the early 2010s and beginning to discover the queer scene here, in my home of East London in particular, I was initially somewhat struck by the realisation of just how many young gay men were involved in sex work of some kind or another. People who at the time I might not have immediately associated with more traditional ideas of sex work, but rather students and recent graduates – young people trying to forge careers in the creative industries but struggling to make ends meet, or just looking for a bit of extra cash on the side to help fund their studies.

Having heard multiple stories of peers beginning their journey into sex work perhaps by casually accepting a paid proposition on an app like Grindr – and having enjoyed the experience, then perhaps going onto set up a profile on an escorting website – it’s clear that the emergence of app-based hook-up culture has lowered the threshold for people experimenting with sex work and generally blurred the lines between different types of transactional relationships.

- Yes, LGBTQ+ Pride still matters. A lot. Here’s the many, many reasons why

- Our history is way queerer than you think – here’s why that matters

- ‘We don’t live single issue lives’: This exhibition is celebrating trans joy amid the culture wars

Facilitated by the digitalisation of our lives, sex work as it is mostly experienced by young gay men in London in 2025 has significantly shifted away from outdated notions of the profession – working the street or in a Soho walk-up.

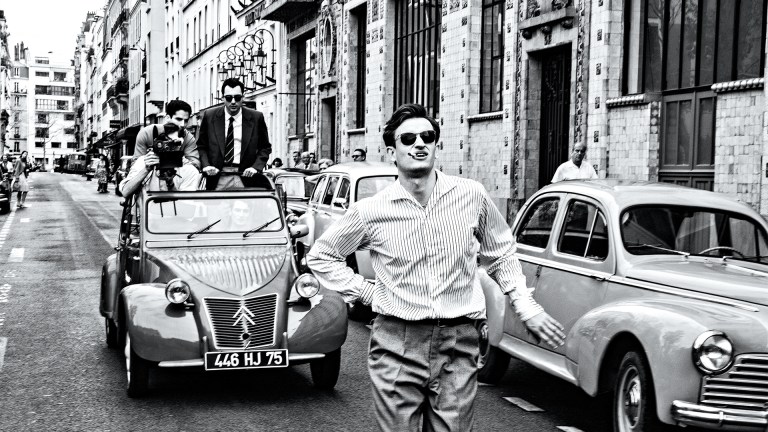

In my film Sebastian, I was interested in crafting a portrait of queer sex work within this newer context, particularly thinking about it as existing within the city’s gig economy, where sex work may form just one arena in the life of a character who is caught in the middle of a number of pressures on his existence and identity in London.

In a way, I really wanted to explore sex work as just another option in the big city’s fast-evolving gig economy, and through this juxtaposition with the other aspects of Max’s life, seek to interrogate any still lingering stigmatisation and the devaluing of sex work in comparison with the other kinds of work that the character in the film engages in, namely, being a journalist and a fiction writer.

Through the juxtaposition of this double life, I also wanted to question any perceived incompatibility between these two pursuits: Why should sex work continue to be so stigmatised; why shouldn’t a person be publicly and openly allowed to be a sex worker at the same time as, say, a journalist, without judgement?