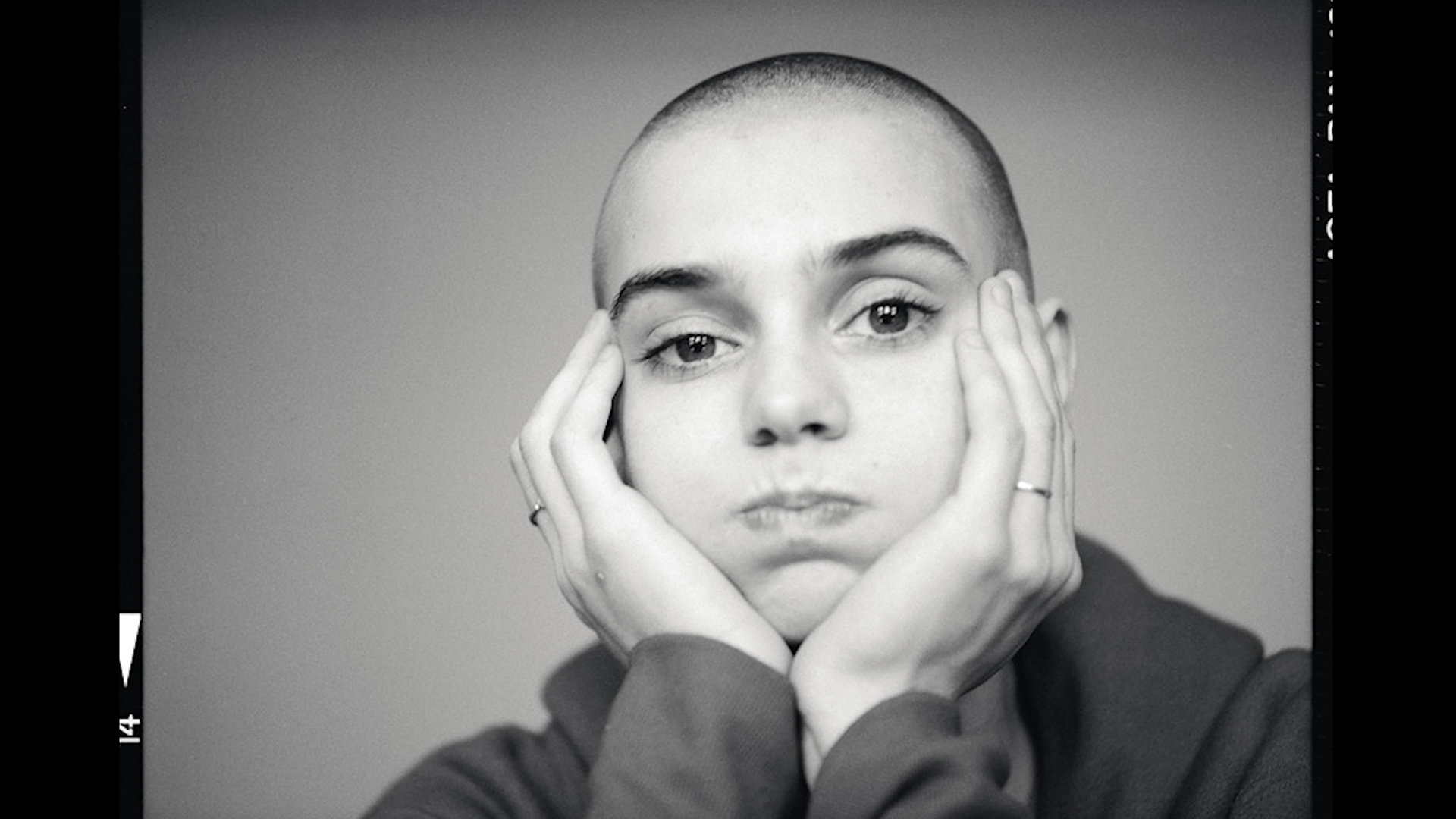

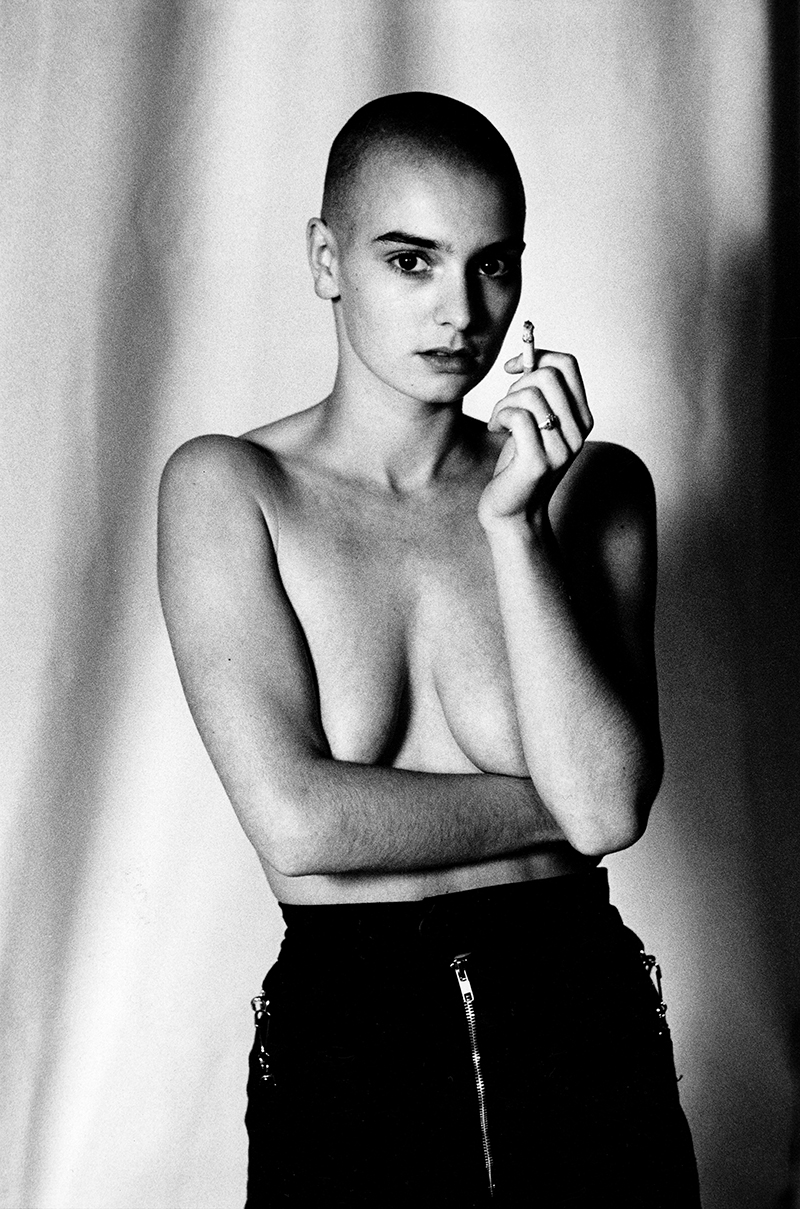

In a long, white lace dress, her huge eyes locked straight into yours through the TV screen, hair shorn to a brown fuzz that somehow emphasised both her fragility and her power, Sinéad O’Connor tore her career in half.

It was 3 October 1992 and the Irish singer was on top of the world. Her version of Prince’s Nothing Compares 2 U had catapulted her to international superstardom. Her second album, I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, had sold seven million copies worldwide and won a Grammy. She’d been invited to fill the prestigious musical guest slot on Saturday Night Live to promote her follow-up album Am I Not Your Girl? and performed an electrifying a cappella version of Bob Marley’s War. Then, as she sang the word “evil”, those beautiful eyes flashed, she held up a picture of Pope John Paul II… and ripped it to pieces.

It was a protest against widespread child sexual abuse in the Catholic Church – something that nine years later would be admitted by the pope – but the world was not ready to listen. She had gone too far. The outrage was swift, the backlash brutal and global.

The front page of the New York Daily News branded her a “Holy Terror”. Catholic organisations pressured record stores to pull her albums from their shelves. Madonna ridiculed her. Public figures competed for the most repulsive ways to denigrate her. On the following week’s SNL, Joe Pesci said he “would have given her such a smack”. So-called feminist academic Camille Paglia said, “in the case of Sinéad O’Connor, child abuse was justified”. O’Connor and her team received bags full of death threats. Her career never really recovered.

Director Kathryn Ferguson – then a pre-teen schoolgirl and passionate Sinéad O’Connor fan – watched on. And she heard the lesson. “She’d been playing on MTV constantly, then she just kind of vanished. It showed me: here’s somebody that’s amazing and incredible, and she’s been dismissed and reduced to the point where I can’t see her any more,” she says. “What does that say to a young woman? You say something that’s important, and that’s what happens? For me, as a young Belfast girl, it was just demoralising. And it left an emotional dent on me.”

In that moment “the seeds were sown” for Ferguson’s fiery documentary, Nothing Compares, which traces the roots of that explosive action back to O’Connor’s childhood in the intensely Catholic, regressive, deeply misogynist Ireland of the 1970s and ’80s.