Virginia McKenna was one of Britain’s biggest movie stars of the 50s and 60s, starring in films like A Town Called Alice and Carve Her Name With Pride. She also got to know Yul Brynner pretty well, playing opposite him on stage in The King and I hundreds of times.

The mane role she’s remembered for today, however, is in Born Free, based on the true story of Elsa the lioness, orphaned as a cub, raised by humans then released back into the wild. McKenna starred as naturalist Joy Adamson with husband George played by McKenna’s own husband, the late Bill Travers.

The couple then became animal rights activists, setting up Zoo Check with son Will in 1984, which evolved into the Born Free Foundation in 1991. Today it still fights for an end to keeping animals in captivity and wider conservation issues.

Recently celebrating her 90th birthday in June, Virginia McKenna talks to The Big Issue from her home in the Surrey hills, joined by son Will and Romanian rescue dog Suzi, about how she’s seen environmentalism change since she made Born Free 55 years ago.

The Big Issue: First of all, how were the 90th birthday celebrations?

Virginia McKenna: Well, it was quite overwhelming. I’m jolly lucky, aren’t I? I don’t feel my age. I don’t really know what a 90-year-old person feels like.

Did you know when you accepted the role in Born Free that it wasn’t just an acting job but a whole new direction in your life?

VM: We knew it was going to be a very different kind of film because I don’t think many actors have been asked to work with lions in the way we did. We worked closely with five but there were, in all, with cubs probably over 20 lions used on the film of different ages and sizes.

We didn’t know they’d all been promised to zoos and safari parks but we managed to save three. Boy and Girl, the mascots of the Scots Guards, and a large male from the Nairobi animal orphanage. These three became wild. Girl produced her cubs. Sired by her brother, I understand.

Born Free explores the pressures between wildlife and local populations. Since the ’60s these issues will have only intensified, won’t they?

Will Travers: I suspect there are few, if any, parts of Africa where you could now re-wild formerly captive lions. When Born Free was made, the lion population in Africa was probably about 100,000, it could have been as much as 200,000. Now we’re down at 20,000. The human population in Kenya alone since the film was made has gone up five times, from nine million to just over 50 million people today.

Space for wildlife is at a premium. That’s not to say there is no space. Kenya has one reserve alone that’s the size of Wales and there are similarly large national parks in Tanzania and South Africa and all sorts of places.

How was the Born Free Foundation born?

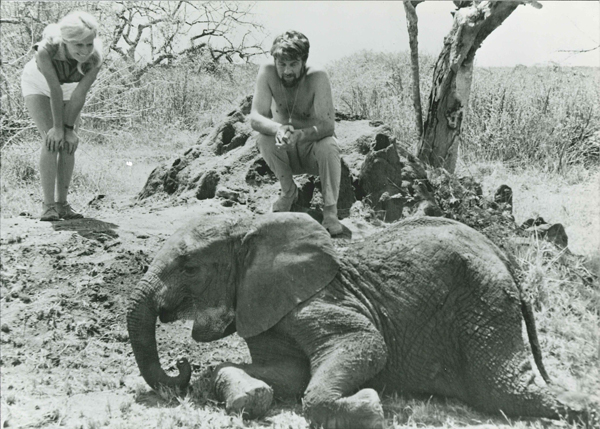

VM: It started not because of a lion but because of the death of an elephant. In 1968, Bill and [Born Free director] James Hill made a film called An Elephant Called Slowly. We learned that they’d captured a little two-year-old elephant from the wild as a gift to London Zoo by the [Kenyan] government of the time. We went to see her and she was so terrified. She became the most wonderful little elephant in the film, as anyone who’s seen it will tell you.

At the end of the filming we asked if we could buy her so she wouldn’t go to London Zoo. The government said yes, you certainly can, but we’ll have to capture another. It was the most terrible decision of our lives. There was no way we would have said, oh, yes, capture another one. It’s the whole family that’s affected, notjust the one little creature. So we had to very reluctantly to say we wouldn’t go ahead.

She came to London Zoo and was there for about four years. Bill had gone to see her and took her some fruit. I was a coward and couldn’t face it. But then we heard something awful was going to happen to her and when we went to see her she recognised our voices. She put her trunk across the moat to touch our hands. After so many years, she remembered us.

We started a campaign to help her return to the wild, but the zoo refused. They did say that they would send her to Whipsnade, where at least she’d have companions. Unfortunately, they kept her standing in her travelling crate for so many hours that she collapsed. They said she’d lost the will to live, and so destroyed her. It was her death that started our tiny little group called Zoo Check. Captive wildlife was the focus of all our attention in those first years, and we changed it to Born Free when you were doing a lot in Africa and dad said Zoo Check doesn’t quite fit it anymore.

WT: We started saying – well, if we’re not in favour of zoos, what do we want instead? That was when we started to embrace more field conservation activities and looking at policy issues. The voices that we hear, from Greta Thunberg to David Attenborough to ourselves, seem to be coming together now in some kind of harmony. It may have been discordant to start with, but right now we are singing pretty much off the same hymn sheet.

The sad thing is, at the moment it’s falling on deaf ears when it comes to those who we’ve elected to represent us and to deal with these issues.

Do zoos have any positive role to play in the conservation movement?

WT: If you go back to the genesis of the modern zoo in the UK, it’s London Zoo, 1828. We’re getting on for 200 years of this particular social experiment. The keeping of exotic animals in captivity, at the time, was broadly a representation of the power and reach of the empire – bringing back strange animals from strange lands that we just happened to also be running at that moment in history. Zoos have tried to reinvent themselves – conservation centres; it’s all about educating kids.

Those claims don’t stand up to proper scrutiny. Take conservation. The range of species that are held in British zoos, on average, 74 per cent are of least concern, according to the IUCN [International Union for Conservation of Nature], , the most reputable scientifically based conservation body in the world. What are we doing keeping all those other species if they’re not a conservation priority? How much money is spent by the best zoos on practical conservation measures? It broadly ranges between about 4.5-6.5 per cent of turnover. And that’s not a big conservation dividend in anyone’s book.

Then look at education, taking the kids to the zoo. I completely get it, the rush that you get when you see an elephant or a giraffe for the first time when you’re five years old. The problem is that’s far too simplistic an analysis of the cost that the animal has to pay in order for a child to have that experience.

As far as I’m aware, there is no evidence that this is a major driver for kids to become fascinated by and interested in nature. There are 700 million zoo visits a year and yet zoos are not regarded in any shape or form as a major driver of the interest in the plight of the natural world.

VM: We’ve been in this [pandemic] for over a year. I hope it’s made a lot of people more sensitive to the confinement of wild creatures. I think a lot of people have found an unexpected joy in the silence of the skies, not hearing planes cracking overhead all the time, hearing birdsong. Their attention is more focused on that wild creature because it’s free. They’ve been cooped up in a room for months and months on end and had no freedom and I think that this, hopefully, might make people understand a little more deeply what freedom to express your own true nature means, whether you’re animal or human.

WT: It can be done, but we all need to do our bit. I’m kind of sick of people saying, “Well, when are they going to do something about it?” What do they mean by “they”? I’ve lost faith in “they”. I have faith in us. And if we all do our bit, that’s when things turn around.

VM: That’s what the young people are thinking.

Is that what gives you hope for the future?

VM: Young people with ideas of compassion. But not in an airy-fairy way, realistic compassion. What can be achieved. I’m so encouraged by how much they really care. They risk being ridiculed.

We’ve all been laughed at. But more and more people have agreed with our point of view when they’ve really gone to see animals in captivity. They look at them with a more informed eye.

I remember when I was a child, very young, must have been about seven, being taken by my father to London Zoo and going into the lion house. They didn’t have an outdoor area. They lived in four concrete cages. I shall never forget the sound of the door clanging shut as

I went in then the clanging as I closed it. Even then I thought, they hear that clanging who knows how many times a day. Some creature coming to stare at me and maybe laugh and point a finger.

To this day, I’ve never forgotten it. When I was 10 and evacuated to South Africa, a school friend said she and her family were going to Kruger National Park for the weekend and invited me along. I saw three lions under a tree! I saw them and thought of the ones in the concrete cages and I thought, there’s the choice: we allow animals to be themselves and fulfil their nature, or we impose our wishes on them. And I know which side I’m on.

WT: I’m a little bit worried about the next generation, not because they don’t have the enthusiasm. We’re dealing them such a bad hand. The responsibility is on us to get this sorted, and we can. It’s been estimated that the cost of investing in nature, in a way that makes it really sustainable, is about $600bn to $700bn a year. Of course, that sounds like a huge amount of money, but it’s not in global terms. It’s 0.5 per cent of the G20’s GDP.

We managed to mobilise something in the order of $30 trillion to deal with the pandemic. I don’t think future generations will say that was a fair swap – not looking after our planet because we were wedded to a race for mutual self-destruction. Not because we’re going to blow ourselves up with nuclear weapons, but because we’re going to destroy the environmental fabric on which we absolutely depend. All of us.

Find out more about the Born Free Foundation, including information on their latest campaign to protect tigers at bornfree.org.uk