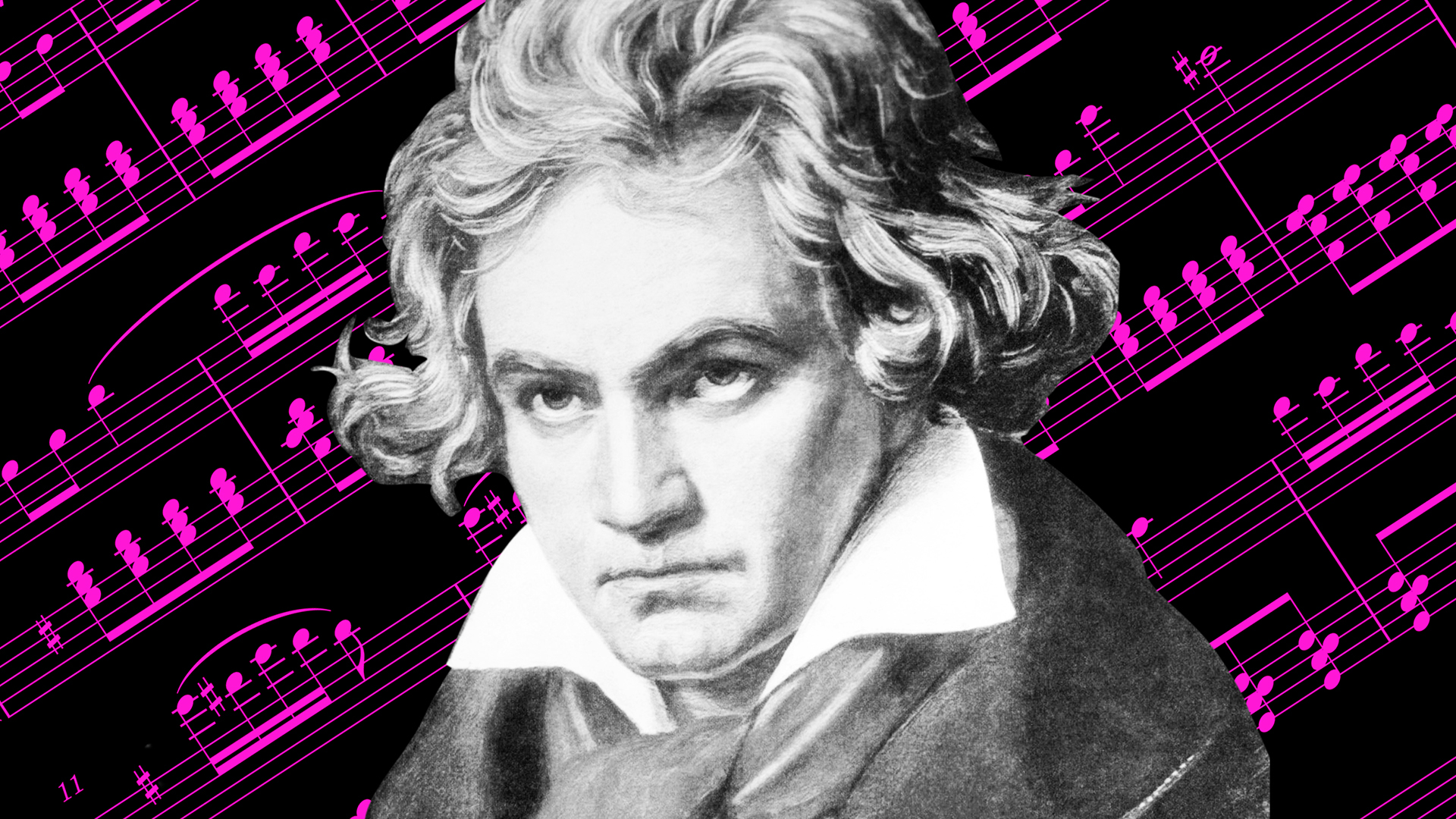

Beethoven never owned a suit.

While he was getting dressed to conduct the premiere of the ninth symphony, friends found he didn’t have a conducting jacket and had to rustle around for one that fitted his ungainly frame. Beethoven was careless of his appearance and reckless in his public conduct. Staggering home one night from a Viennese tavern, he was picked up by a police patrol and charged under the vagrancy laws. When he announced himself as Beethoven, the cops escorted him, rather respectfully, home.

Everyone knew Beethoven. He was the wild man of Vienna and, at the same time, the most famous composer that ever lived. The question is, which was the essential Beethoven?

Your support changes lives. Find out how you can help us help more people by signing up for a subscription

His volatility was a distinguishing feature. The Freudian psychoanalyst Theodor Reik writes: “One cannot say he lost control because he had almost none.” Household staff were forever leaving him, minutes before he threw things at them. Newcomers were warned to duck. After the tumultuous first performance of the ninth symphony he booked dinner for himself and three friends at a restaurant on the Prater. Before leaving the concert hall, Beethoven stopped by the box office to check the evening’s meagre takings. He arrived last at the restaurant, roaring at his friends that they were stealing from him. All three walked out on him. On the night of his greatest triumph, Beethoven was left to dine alone, an image so pathetic it is almost defining.

Why did he act like that? One root cause is an alcoholic father who beat him and left him untrusting of those around him. Then there’s the deafness and the loneliness. He lost almost all of his hearing by the time he reached 30, the worst tragedy that could befall a musician. Deafness cut him off from colleagues and companionship, making it impossible for him to form loving relationships – if, indeed, he ever wanted to. Beethoven fell in love with a string of pretty young women who were, invariably, out of his class and beyond his reach. They had an eye out for a rich count, not a disheveled musician. Time after time, it ended with Beethoven pouring his broken heart into a song cycle or a piano sonata. So consistent was his failure in love that it was as if he was attracted only to women who would reject him. He needed to experience the emotion of love without the physical engagement. So far as it is possible to ascertain, Beethoven never had sexual relations.