I’m sitting in my kitchen in Liverpool playing with my favourite app, Radio Garden, and it is a thing of beauty. When you open it, you see a globe spinning through space, like on Google Earth. You turn the globe with your finger to any continent you like, zoom in by pinching the screen until a country or a city takes your fancy, and tune into one of 30,000 radio stations.

There’s nothing like music to transport you, instantly, to a faraway culture. Radio Garden’s sonic tourism is a fix for travel-hungry people marooned by Covid-19. But something deeper is going on because, to take the long historical view – as well as the view from space – our ability to encircle the planet through music brings that evolutionary story to its climax.

Music’s journey to world domination began literally with the first step; when humans’ oldest known ancestor, Ardi the australopithecine, got up on her hind legs 4.4 million years ago and walked. Why? Because bipedalism, walking upright on two feet, forged vital neuronal links between brain, body, and sound, and stamped hominin music with its characteristic walking rhythms. It forever associated music with motion and travel. This is why human music ‘dances’ and ‘walks’, and why it feels so natural that music today soundtracks our lives via our iPhones and earbuds as we saunter or jog through cities.

The journey from australopithecines to soundtracks is traced in my new book The Musical Human. Pooling together evidence from archaeology, anthropology, biology, and the psychology of hearing, I make the case that music drove human evolution: that music was the most important thing we ever did.

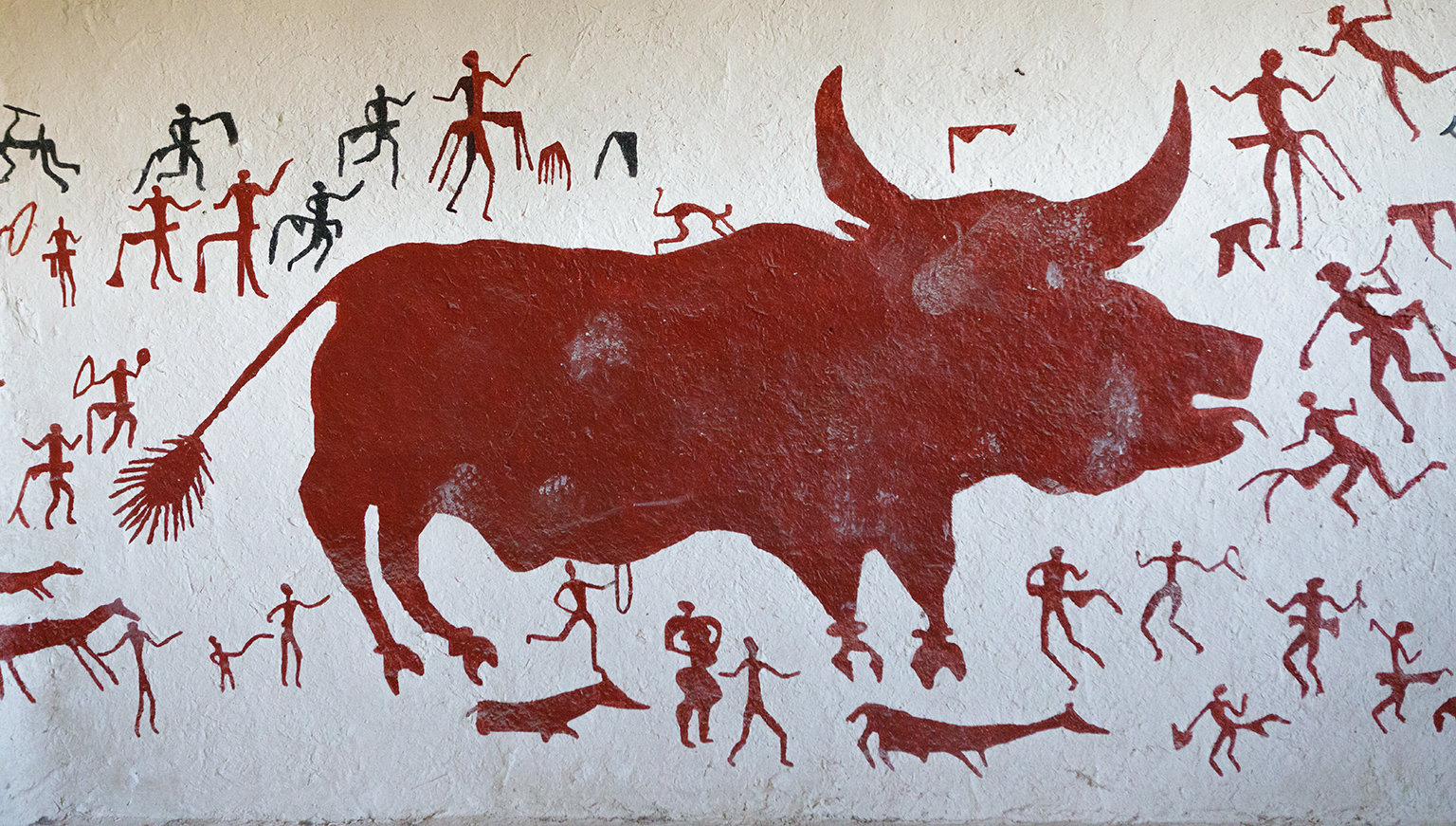

After Ardi and her more famous descendant Lucy (3.2 million years BC) starting walking, 1.5 million years ago rhythmic patterns helped Homo ergaster knap flint tools; rhythm coordinated communal labour. Some 500,000 years ago, Boxgrove in Sussex was the site of celebratory ritual dances, as music brought Homo heidelbergensis together into a community. Then, 250,000 years ago, Neanderthals perfected a sing-songy, musical kind of communication. And 40,000 years ago sapiens crafted the first musical instrument out of vulture bones as part of humans’ cognitive revolution.

The skill to make bone flutes coincided with sapiens’ ability to paint figural representations on cave walls, carve figurines, such as the famous Lion-man sculpture discovered in the Hohlenstein-Stadel Cave in Germany, and, presumably, the acquisition of language and conceptual reason. Yet at every stage of human evolution, music was there before language or reason.