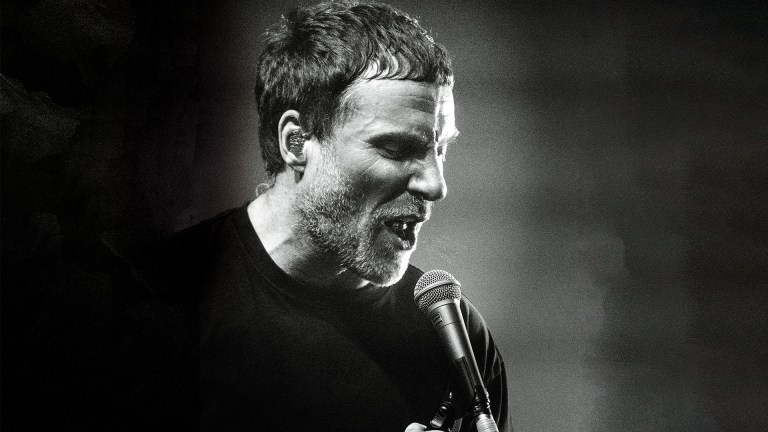

From poetry slams to huge crowds at Glastonbury by way of house parties, underground raves, literature festivals, political demonstrations and the Royal Shakespeare Company, her star has risen by a uniquely circuitous route. Yet she’s built her reputation through gritty urban sagas inspired by the grime, graft and grift of the Big Smoke, not the manicured gardens and sea views of sun-kissed California. Her words whether written, rapped or spoken don’t recline in paradise, but rail against social injustice, racism, corruption, celeb culture and the slow death of common compassion in rubbish modern life.

Nonetheless, Tempest’s ascent to working with one of the biggest music producers of all time – indeed, she’s the first female British solo artist since Adele to record at Shangri-La – shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone. At 33 she already has a pair of Mercury Prize nominations under her belt for each of her two albums to date – most recently 2016’s Let Them Eat Chaos – while her debut novel, The Bricks That Built the Houses, published by Bloomsbury in 2016, was a Sunday Times Bestseller. Her stage has long been set for bigger things.

It was during a frantic spell of work in 2014 that Tempest got a call from her literary agent to say someone highly unexpected was trying to reach her after catching a performance on US TV by chance.

Enter Rubin, the Long Island punk who co-founded Def Jam Records from his NYU dorm room in the early 1980s and went on to build a towering reputation as a Yoda-like production guru for hip-hop, rock, country and heavy metal’s great and greater still. He’s the man who broke the Beastie Boys with Licensed to Ill, turned the Red Hot Chili Peppers into one of the world’s biggest bands with Blood Sugar Sex Magik, helped rouse Johnny Cash to his final triumphs with the American Recordings series and made sense of Kanye’s sprawling Yeezus. And for Kate Tempest, out of nowhere, he was on the phone.

“I wasn’t very prepared to know how you deal with that,” Tempest admits. “He has got the power to just reach out to anybody and say ‘What are you up to, do you want to do some stuff?’ And so we came here, we started writing.”

Tempest and her regular writer-producer collaborater Dan Carey would spend several weeks on and off at Shangri-La over the course of several years, slowly nurturing and eventually recording what would become The Book of Traps and Lessons. It was a challenging and at times gruelling process. A stripping-back and shedding of layers and years of conventions and experience, all in pursuit of living up to an epiphanic vision that Rubin, the ultimate vocalist’s producer, had for unbridling Tempest’s flow from rap’s natural driving force of the beat and letting her words run free to her own internal rhythms. The results speak for themselves. Tender, intimate, atmospheric, dense and deeply personal, The Book of Traps and Lessons is undoubtedly striking, and possibly groundbreaking. Rubin says it has the potential to be a gamechanger for modern hip-hop.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Carey’s music – deceptively complex but rigorously unshowy – churns and broods and drones in the background, giving Tempest’s rapid-fire lyrics space to breathe. A sense of social consciousness and political ire fires her work as on previous albums, but her narratives are less character-based and more first-person. Opener Thirsty sets up a record on which affairs of the heart push to the fore through evocative lines like ‘I saw her cross the floor like a firework exploding in slow motion’.

“I just spent a year basically living in the mountains between France and Spain with my partner, and that was the first time I’d ever left south-east London,” Tempest says, hinting at the reasons behind a shift in focus in her poetry. “South-east London is not massive. I’ve lived all over it, and never anywhere else. Thirty-three years of life, apart from I just spent a year living in the middle of fucking nowhere in the foothills of the Pyrenees. That’s only in France. And I still felt I was too far from home.”

Brown-Eyed Man – a track Rubin rated so highly he invited Beastie Boy Mike D over for a listen (“just crazy,” Tempest remembers, shaking her head in disbelief) – rages and despairs at institutional racial violence. One of just a handful of songs on the record set to a drum beat, the soulful Firesmoke lavishes in a lover’s touch (‘Your body is home to rare gods / I kneel at their temple’), while People’s Faces, hung loosely around a rousing piano line, closes on a hopeful note that simple human empathy may yet deliver us from these divisive, Brexit-y times.

“The lyrics have been set free,” says Tempest proudly, able now with the benefit of hindsight to admire a logic that wasn’t always easy to appreciate in the thick of the album’s making. Famously, Rubin, a completely untrained producer, is much less concerned with the perfect positioning of a microphone or the precise tuning of a guitar than he is in intuitively establishing an uncluttered and truthful relationship between an artist and their material.

He knows what he needs to do to be most useful to you

“He doesn’t touch the equipment,” Tempest says, “he just listens. He’s not in the whole day, he comes in for like an hour. At first, we were like, ‘We’ve come all the way here, where is he?’ Now I see what’s beautiful about it is that he knows what he needs to do to be most useful to you, which is that he comes in, fully charged, ready to listen. So when he comes in, you better have some stuff to play him.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

“He listens to what you’re doing, and then he talks about it with you. And then he goes away. And you spend the rest of the day and night digesting what he said. It does your head in, you can’t work it out, it doesn’t make any sense. Then he comes in again the next day and does it all again.”

Besides making sure you’ve got some music to play for Rubin, you’d better make sure the place is tidy too. “I’m sure you’ve noticed that the studio is spotless,” Tempest notes, lowering her voice conspiratorially, “like, there’s not even any wires anywhere. And then when me and Dan were in here there was shit everywhere,” she laughs. “Boxes. All the fucking notepaper. Every time the engineers would come in, they’d be like ‘Rick’s coming in in an hour. Fucking clean up!’

“Basically the whole studio, everything here is engineered for him to be able to walk in and listen, this is what this is,” Tempest explains, gesturing her arms around. “That’s what he does. When he walks in, everything changes, because suddenly you’re aware of how intensely somebody is listening. It’s so loaded.”

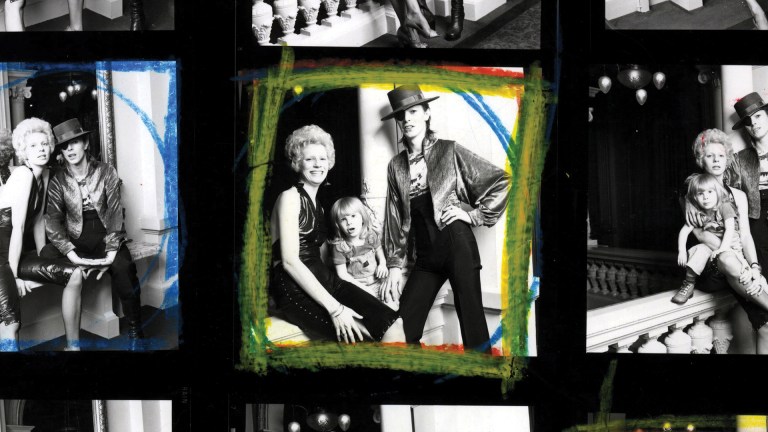

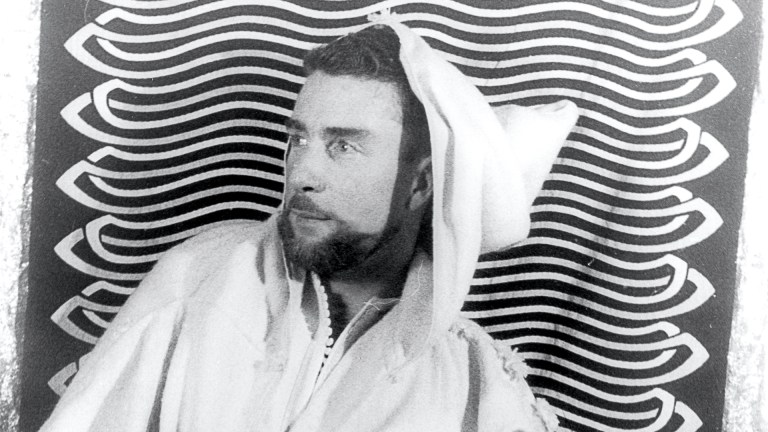

Rubin ambles into view across the lawn– a 56-year-old so horizontally laidback-looking it’s hard to imagine him ever moving at anything other than an amble, except maybe for when he’s levitating. He and Tempest hug and share their excitement at their long-gestating creation’s imminent release. Their connection is plainly warm and mutually valued.

Skin baked a deep brown, rocking a bleached-out and wildly unkempt beard that properly puts the Santa in Santa Monica, he’s a picture of Californian health. The three of us assemble at some patio furniture and Rubin – a man to whom, for all his reported $250m worth, socks seem complete anathema – props his bare feet up on the table edge. Where Eno has his Oblique Strategies and Phil Spector waved a gun around, Rubin’s production philosophy is that bit more subtle: tuning his ear and searching for clues, as if piecing together a complex cosmic puzzle from the frequencies of the universe. He peppers our conversation with phrases that could be the teachings of some kind of musical spirit guide. “In free poetry, the language is the king,” he muses at one point. “So much of this is not intellectual, it really is more heart-based, feeling-based,” he cogitates on another occasion. Tempest nods along approvingly, absorbed in her mentor’s wisdom.

What did Rubin see as his role in the making of The Book of Traps and Lessons? “It was just a vision for this free, poetic vocal to be able to work in a hip-hop environment without it becoming a traditional hip-hop record,” he replies, crisply. “That was pretty much the abstract dream.”

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Rubin was, he remembers, “very moved” by that first exposure he had to Tempest’s poetry on US TV, and immediately felt compelled to reach out. “I saw the connections to rap,” he explains. “I didn’t know that you had ever done rap at that time. I just thought you were purely a poet, a traditional poet, and there was tremendous energy and passion in the performance of the poetry. And I thought, ‘Wow, if that was brought into the musical world, that would be a very powerful thing.’ It was just seeing something in Kate. And trying to protect it, this magic thing that you do.”

It’s not often that Rubin feels compelled to intervene in an artist’s career like that. “So when it does happen, it’s really exciting,” he says. “I can’t even remember [the last time that feeling hit],” Rubin says. “But one of the first times would be Public Enemy.”

He thinks The Book of Traps and Lessons’ potential to influence other rappers is considerable. “In some ways it’s like the rules of rap are fairly strict,” he elaborates. “And if a rapper gets to hear this, it just could really open the mind of what’s possible and in different directions.”

Does that mean he’ll be pushing copies of it to the Kanyes and Kendricks? “Whoever I think will like it I’ll share it,” Rubin acknowledges. “While Kate was here, Jay came and visited and listened,” he adds. “I remember he listened to three works in progresses. And he said, ‘OK, I’m going to go home. I know what I need to do now.’”

“It was surreal, you know,” Tempest jumps in, “when Jay-Z came into the caravan and listened to our songs and said, ‘I’m going to go home and do some writing.’

“And then we had a really interesting conversation about his writing and where he was and the next thing that he released was this record where he was really doing new things with his lyrics [2017’s 4:44].”

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Slaves to the Spotify algorithm who rarely see much money from their work, do artists today have Rubin’s sympathies in their struggles to build a career? “I’d say it might be easier to at least be heard now than ever before, but it may be harder to affect the culture in a way that used to be possible,” he says. “There was a time when a big release would change the culture. It feels like that doesn’t happen.”

“It feels almost like an album is a dated idea,” he states later – a slightly surprising admission from someone who has built his life around making albums. He’s confident that there will always be a role for producers, however, even as artists increasingly pivot away from lavish studios such as Shangri-La towards more low-budget DIY practices.

“I think the nature of music tends to be collaborative,” he says. “And having someone who wants it to be as good as it could be, but doesn’t have any of the emotional attachment to the material itself, on the outside, is really helpful. The same is true for people who write books, having an editor. While you might not always like what the editor says, it helps the process to have a trusted source to bounce material off.”

Does Rubin feel as inspired by music today as he did 20 or 30 years ago? “Absolutely,” he reacts, unhesitatingly. Is the day when he doesn’t feel as excited by music the day when he’ll retire? “I don’t know,” he smiles. “It hasn’t happened yet.”

And with that, he says his polite farewells and levitates – OK, ambles – across the grass into the house, urging Tempest to join him so he can play her some new music that he’s been enjoying. I’m left in the gardens awaiting my lift back in to LA, peacefully alone to the sun, the ocean, the butterflies and the frequencies of the universe, reflecting agreeingly on Tempest’s earlier to-the-point assessment of coming to Shangri-La: “this is the shit you dream about.”

The Book of Traps and Lessons is released on June 14, (American Recordings) katetempest.co.uk

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty