The term ‘classical music’ has so many interpretations it’s almost become meaningless as a description. It’s used as an umbrella for any and every form of ‘art music’, from Mozart to Messiaen to Anna Meredith. Classical music has much in common with the word ‘conservative’: a capital ‘c’ makes a big difference. Classical music (with an upper-case ‘c’) denotes a movement in music that came after the Baroque period and before Romanticism. (Roughly speaking, music composed between 1750 and 1820; think Haydn, Schubert and early Beethoven.) Then, there are other issues: should ‘contemporary’ music – meaning music created over the past few years – have its own section (as it does at some major arts venues – the Barbican Centre, for example)? And should music that crosses into other genres – such as post-classical, which often borrows from electronica and pop – be gathered under the same heading?

But just as importantly, ‘classical music’ generally implies Western art music. And while that genre is more than enough for a lifetime’s exploration (due to the sub-categories mentioned above, plus the fact there’s 800 years of the stuff), there are many other worlds of classical music. (My colleague Michael Church has produced an excellent introduction to some of these in his book The Other Classical Musics.) Collaboration is making barriers porous, and the results are new, exciting sounds. One example is the pianist-composer Fazil Say, who in works like 1001 Nights in the Harem and Grand Bazaar combines traditional Western orchestration with instruments from his native Turkey, such as the ney reed flute. Another is Philip Glass, whose opera Satyagraha – inspired by Mahatma Gandhi – is sung in Sanskrit.

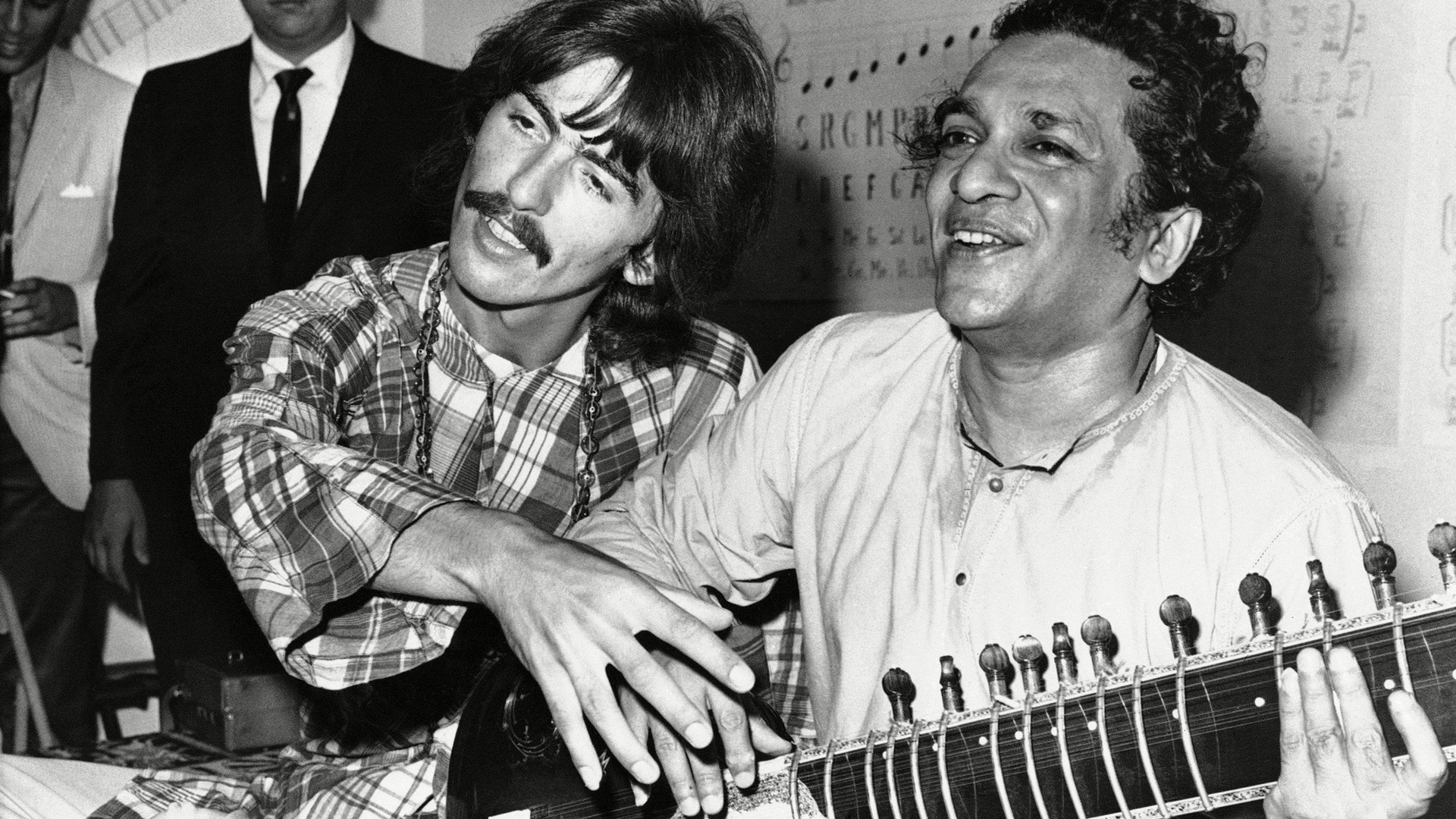

Sitar supremo Ravi Shankar (1920-2012) turned up the heat on this melting pot. His music combines ideas from both East and West, and his legacy is more than just virtuosic playing. His centenary this year is celebrated by the Southbank Centre’s mini-series Shankar 100. The programme kicks off with a special performance of Shankar’s only opera Sukanya (January 15), which tells the story of a princess who is forced to marry for the sake of her kingdom. The libretto (written by Amit Chaudhuri) is inspired by the Sanskrit texts of the Mahābhārata. The semi-staged performance features Southbank resident ensemble the London Philharmonic Orchestra, with British soprano Susanna Hurrell in the title role, alongside Indian-born American tenor Alok Kumar as Chyavana, her prince.

It’s a work that the Philharmonic knows well, having performed it back in 2017. That rendition was recorded and is being released for the first time to coincide with the centenary.

Similar in name and address to the London Phil is the Philharmonia Orchestra, which celebrates its 75th anniversary in 2020 (the ensemble is also based at the Southbank). Philharmonia at 75’s opening concert (Royal Festival Hall, January 16) is themed around the French horn, showing there’s more to the instrument than the baddie theme in Peter and the Wolf. The Philharmonia has strong connections to the French horn: Dennis Brain, who popularised the instrument after the Second World War and inspired many composers to write for him, was a member of the ensemble until his untimely death aged 36. (He died in a car accident while driving home from a Philharmonia concert in Edinburgh.) Britten’s Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings was one of the works he was closely connected with (he gave the premiere in 1943); Richard Watkins is the horn player for this concert, he also premieres a new work by Mark-Anthony Turnage.