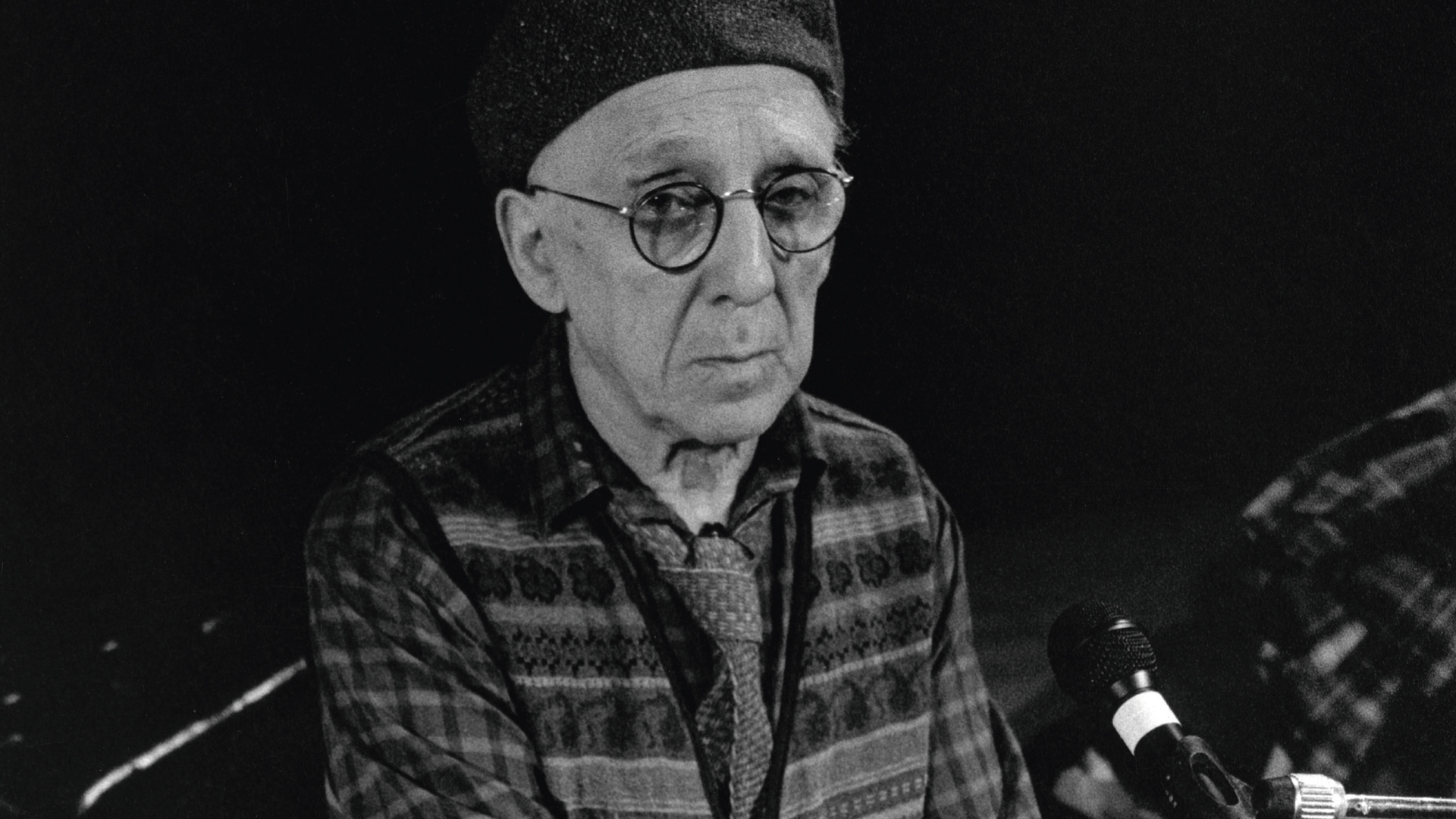

Set to be launched this week with a one-off concert in Glasgow as part of the Celtic Connections festival, Return to Y’Hup: The World of Ivor Cutler is a fun, fitting and surprisingly very first album tribute proper to one of the great nearly-forgotten cult heroes of Scottish and British music history. Born in Govan, Glasgow and based for much of his career in London, glowering bespectacled humourist, poet, philosopher and surrealist Cutler (1923-2006) was an inspiration for The Beatles, who cast him as Buster Bloodvessel in 1967’s Magical Mystery Tour. He played more Peel Sessions than anyone except The Fall, and released material across six decades on labels from EMI to Harvest, Rough Trade and Creation.

Never heard of him? That’s maybe not surprising given that Cutler – a member of the Noise Abatement Society, who disliked amplified music and would request that his audiences applaud at half-volume – was a marginal figure in many ways by his own eccentric design. Yet his influence is great, as the list of guest performers on Return to Y’Hup confirms – from Franz Ferdinand’s Alex Kapranos to

Camera Obscura’s Traceyanne Campbell, Belle and Sebastian’s Stuart Murdoch, Robert Wyatt and even Cutler’s partner of 40 years Phyllis King.

Why aren’t our cultural custodians better at permanently preserving the tactile legacy of popular music?

The musician-academics behind the project, Glasgow University’s Dr Matt Brennan and Edinburgh University’s Professor Raymond MacDonald, have succeeded in creating something not only quirky, affectionate and immersive, but which also thoughtfully platforms Cutler’s output for younger and future generations to discover. There’s a phrase they’ve used to describe their work which catches my eye – “a pioneering experiment in the field of imaginary archaeology”. It refers mainly to their exploratory digging up of the fantasy world the album inhabits, Y’Hup, a fictional island of vigorous flora and fauna where Cutler and his coterie of curious characters and critters dwelled. But it could just as easily apply to the way in which they have unearthed for posterity Cutler’s legacy from the shallow dust of music history.

It got me thinking about something I wrote previously for The Big Issue, relating to the Rip It Up exhibition of Scottish pop when it opened in Edinburgh in the summer of 2018 – incidentally the same exhibition which inspired the Cutler album, after Brennan had been left wondering why Cutler hadn’t been represented somewhere in its entertaining sprawl of historical memorabilia. I would echo that thought, and furthermore, use it as an opportunity to again ask: why aren’t our cultural custodians better at permanently preserving the tactile legacy of popular music – at archiving in publicly accessible ways the places, spaces and things which speak to one of the defining art forms of our age?

The BBC announced in 2018 that their Maida Vale studios in London – where Cutler, The Fall and others played so many memorable Peel Sessions over the years – were to close, pending the building’s probable conversion into posh flats. The wheezy harmonium which Cutler played on many of his most famous recordings, and which legend has it he abandoned at Glasgow’s Pavilion Theatre after he – true story – fell out with it, resurfaced at a props store several years ago, before being bought by Celtic Connections director Donald Shaw, who occasionally loans it out to interested parties (it features on Return To Y’Hup, and was used in performances of a Cutler play by the National Theatre of Scotland).

Much of Cutler’s vast archive of lyrics, sketches, artworks, letters, press cuttings and posters, meanwhile – a small sample of which featured in an exhibition at Goldsmith’s CCA in London in 2018 – languish in storage, in search of a proper home. Couldn’t one be found – alongside other items from the Rip It Up exhibition among others – in Cutler’s native Glasgow? A Unesco City of Music, a city with the largest music economy in the UK outside of London? A city famed the world over for its legacies of pop and shipbuilding, and yet which, for some mystifying reason, has a full museum to neither?