One of the many enjoyable quirks of shopping for second-hand vinyl, besides the joy of the hunt and the occasional gem of a find – less so the foosty pong of decaying cardboard – includes the random, curious things which can sometimes be discovered slipped inside record sleeves by previous owners. I have an old Beatles LP, hidden in which I found a bunch of smouldering soft-focus photographs of Paul McCartney clipped from a 1970s girl’s magazine – I know they were from a girl’s mag because there was a conservatively worded advert for Kotex New Freedom sanitary towels on the reverse of one image – along with an A4 page of lovestruck handwritten lyrics to the song I Will, presumably the work of some discreetly yearning teenager.

I’ve heard tales of all kinds of intriguing, weird and dark secrets and keepsakes of yesteryear discovered inside vinyl sleeves – all from gig tickets to autographs, love letters, explicit photographs, even suicide notes. I was struck the other week by a viral tweet of a photo of something someone had found slipped into a copy of JJ Jackson’s 1969 album The Greatest Little Soul Band in the Land, which kicked this strange phenomenon in a whole new direction. “Dear Jake,” begins the freshly typed letter from Fiona, a seller from online music resale marketplace Discogs, addressing the buyer directly by name. “Firstly, may I thank you for purchasing the enclosed LP.” Fiona goes on to explain the history of the vinyl collection she is selling.

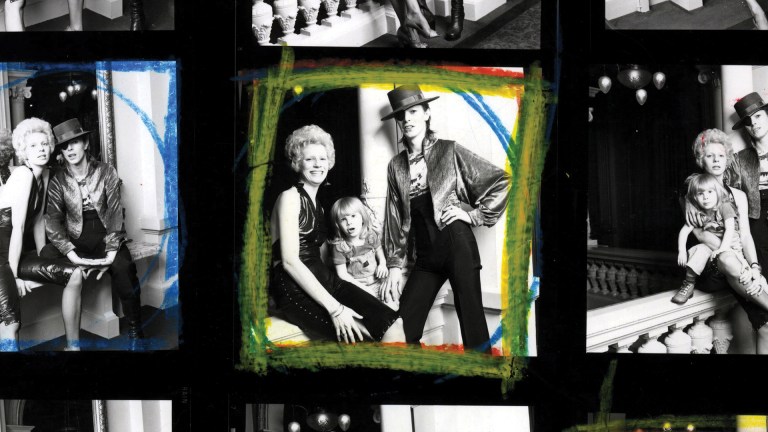

“I lost my parents last year and so I’m currently going through the painful process of clearing the family home.” Her father, it turns out, worked for RCA as an artist liaison manager from the 1960s through to the 1980s, collecting some 3,000 records along the way and becoming friends with the likes of Charley Pride, Perry Como and even a young Dolly Parton (whom he once chaperoned on a sightseeing trip to Windsor Castle). “I’m not a record shop or professional collector,” writes Fiona, “I’m just trying to honour my father’s memory and give his much-loved vinyl some more playing time in a new home.”

There is an eerie feeling sometimes, when acquiring second-hand records – and this letter illustrates it perfectly – of becoming merely their latest custodian, rather than necessarily their owner. In time, as I suppose we shall with music of any format, we will pass it all on to someone else: a friend, a partner, our children. Treasured possessions imbued with silent memories, a weight to be carried or passed on in turn. Perhaps with as much patient compassion as Fiona, but perhaps not. Perhaps our stuff will all just get dumped in a charity shop.

A maudlin thought, maybe, but one worth putting in context amid the current predicament of the so-called “vinyl revival”, which after 13 consecutive years of growth – 4.8 million sales of new vinyl in 2020 – is in danger of downturn. The vinyl production industry is struggling to cope with demand: where turnaround time for pressing was once around 6-8 weeks, it’s now twice that or more. Releases are being pushed back by months – some are going out digital or CD only. Disruptions around Covid-19 are partly to blame, likewise Brexit. But this was always liable to happen – there simply aren’t enough record pressing plants in the world, and no new plants are being built.

Records and indeed record stores shouldn’t just be for a day; they should be for life

It’s one reason why Record Store Day 2021 will be split over two “drop” days five weeks apart this year – the latter to catch delayed releases. Both days will hopefully give a valuable financial boost to shops which have been forced to close for long periods during the pandemic, and form part of a joyous reawakening for the music world after a dismal 15 months. Yet, there’s no getting away from the fact that when it comes to official Record Store Day releases – 450 titles in total this year alone – many are symptomatic of a big problem clogging the vinyl machine and forcing up prices. Namely: an overabundance of stuff which, beyond hardcore collectors and cynical scalpers, doesn’t seem to hold all that much appeal to most music buyers.