I last spoke to Sons of Kemet bandleader Shabaka Hutchings in the autumn, the day before he was booked for a live streamed gig with the Britten Sinfonia at the Barbican. He was feeling relaxed and broadly optimistic, making the most of the spare time lockdown had afforded him to concentrate on his playing.

Hutchings had chosen to perform Aaron Copland’s Clarinet Concerto, a notoriously tricky piece originally commissioned by Benny Goodman for a live radio recital in 1950. Copland was apparently sceptical that Goodman had the requisite skill to perform the music well, despite his status as the King of Swing, and he covertly asked a classical musician to also learn it in case Goodman chickened out. Goodman got wind of this rumour, took it as a cue to practise furiously and subsequently gave what is widely regarded as one of the greatest performances of his life.

Support The Big Issue and our vendors by signing up for a subscription.

Hutchings told me he saw value in honing his clarinet skills the same way, and when we spoke he was reaching the end of a gruelling routine of daily and nightly practice. “For me it’s not about the concert itself, it’s about how it makes me grow as a musician,” he told me. “I’ve gotten what it needs to give me. Even if I were to make a massive squeak on the first note and have it be all downhill from there I’d still be happy.”

Between practice sessions, Hutchings had been adding the finishing touches to his new album with Sons of Kemet, Black to the Future, which is out this month on Impulse! Records. With his laser focus on evolving his musicianship and his sound, it’s hard not to draw comparisons between Hutchings and the many jazz elders who released some of their finest material on Impulse! – among them Coleman Hawkins, John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins. Rollins, in fact, used to practise regularly on the Williamsburg Bridge, competing with traffic and construction noise to satisfy his aspiration of playing consistently at roaring volume. Rollins also understood early on in his career the opportunity he had to make a political statement with his music. He released his epic Freedom Suite in 1958, seeking to rectify the fact that American jazz fans wanted to “hear the black music, but not the black story”.

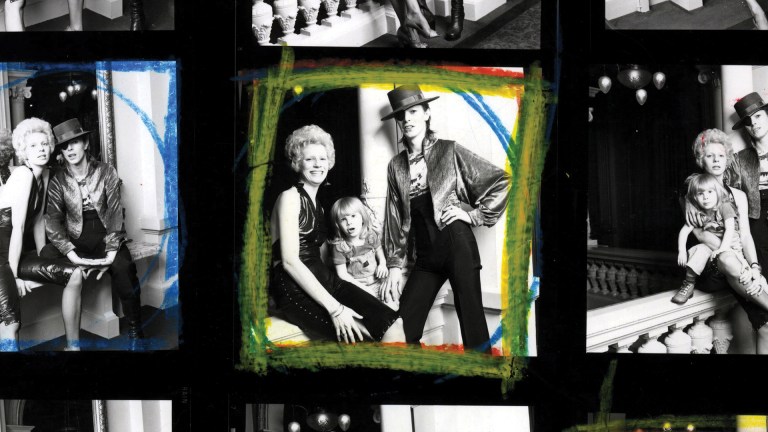

So happy to announce the new @SonsOfKemet album ‘Black to the Future’ will be released may 14th.

Big up Mzwandile Buthelezi for the artwork pic.twitter.com/dxCzzGo2za

— SHABAKA (@shabakah) March 30, 2021