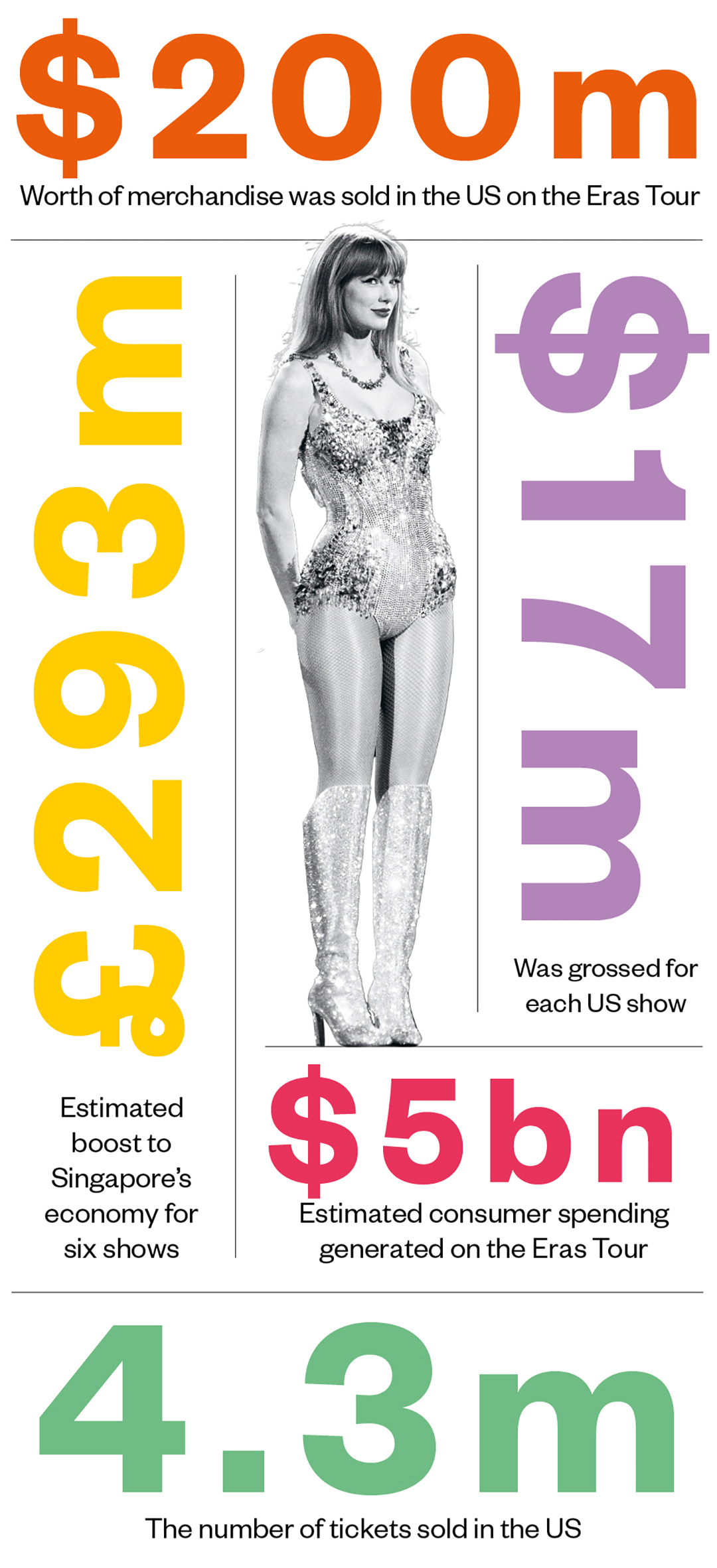

Measuring the economic impact of her tour has become a competitive sport for analysts. Her four Tokyo shows, to 220,000 fans, in February added ¥34.1bn (£183m) to the Japanese economy according to a report by the Economic Impact Research Laboratory.

Each city she stops at is seemingly granted an economic jackpot. This is not trickle-down economics; this is Niagara economics.

Ryan Herzog, associate professor of economics at Gonzaga University, told CNBC, “She is in and of herself an economic event.” It is likely this tour will be a case study on economics degrees for years to come.

The tour has also become a hot-button issue in geopolitics. In early March, Swift performed six shows at the Singapore National Stadium, her only dates in Southeast Asia.

Srettha Thavisin, the PM of Thailand, claimed Taylor Swift was offered subsidies of $2-3m per show to make her Singapore performances a regional exclusive. The Singaporean government disputed the amount, but did not outright deny the accusation of exclusivity economics. Erica Tay, director of macroeconomic research at Maybank, estimated the shows would boost the country’s economy by S$500m (£293m).

The fiscal benefits to Swift herself are clear, but this move in Singapore, if true, feels incredibly anti-fan as those across the region wishing to go would have to add international travel costs to the ticket price. For example, because she had only Australian dates in Australasia, Air New Zealand had to add capacity for 2,000 extra seats to its network “to get fans across the ditch” for her seven shows in Melbourne and Sydney in February. Great for Air New Zealand, not so great for the economies of the country’s biggest cities.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

Amid the blizzard of hyperbole (like music journalists boldly pronouncing we are “in the Taylor Swift cinematic universe”), calm and reason feel like the first casualties. A rolling story like this is catnip to economists and the business pages of the broadsheets, normally commenting on and analysing more staid businesses. A piece hitched to the earnings of a pop star turns a grey numbers story into a glamorous jamboree of wild speculation beyond the hard stats themselves.

In parallel with stories about “the Taylor effect” and “the Swift lift” peppering Wall Street earnings calls, Si Ying Toh, global economist at financial services group Nomura, swam against the tide of hype (possibly being intentionally contrarian) by saying Swift’s tour might have “enchanted US economic analysts” but cautioning the “total macroeconomic effect is probably overstated”.

There are similar, if slightly more muted, claims being thrown about around Beyoncé’s tour in 2023. “Beyoncé blamed for inflation surprise in Sweden,” ran a frenzied BBC headline last June. Her shows there saw surge pricing, an economic force more typically associated with Uber when the late-night bars close or airlines, restaurants and hotels in the run-up to Christmas. This, it was claimed, pushed inflation to a higher-than-expected 9.7% in the country.

Visit Stockholm called it the “Beyoncé effect” and it was compared to what happens when a major sporting event comes to a city.

Below the BBC headline, however, was a more measured interpretation by Danske Bank analyst Michael Grahn, who said he would not “blame” Beyoncé as the single contributory factor, reasoning that her shows “added a little to it”. A headline like “Beyoncé added a little to inflation in Sweden” does not have the same arresting impact.

The other critical issue here is understanding if all this spending beyond tickets and merchandise is additive to the local economy (ie consumers extending beyond their normal spending) or diversionary (taking money that could have been spent on other things and relocating it).

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

We are already seeing the impact in the UK – and Swift’s tour does not even begin until 7 June in Edinburgh. The Black Dog pub in Vauxhall, South London, has seen “overwhelming” footfall from fans as it provided the title for a track on the “Anthology” edition of her new album, The Tortured Poets Department.

When The Rolling Stones toured, the cliché was they were the only show in town. They would arrive and spending in and around the venue would go through the roof. Yet that seems economically restrained compared to what is happening as Taylor Swift creates a new financial centre of gravity in every city she deigns to visit. And it is very much a city-based phenomenon.

Glastonbury is perhaps one of the most economically studied music and culture events in the world. A 2020 House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee inquiry into UK festivals quoted research by the Association of Independent Festivals that found “a 5,000 capacity festival is worth £1.1m to the local area, while a 110,000 capacity festival can be worth over £27m”. This paled in comparison with Glastonbury which “generates over £100m into the economy of South West England each time it takes place”.

The economic impact of festivals tends to lift the local economies in rural areas. Beyond transport and camping equipment, the bulk of attendees’ spending will be on, or very near, the festival site. The Swift tour is inherently urban in its impact, with hotels the immediate beneficiaries but also the wider tourism ecosystem.

What the measurable economic uplift will be for Edinburgh, Liverpool, Cardiff and London when Taylor Swift does her latest victory lap around the UK this summer is currently in the realms of wild speculation. Even so, every other major city in the country will have new empathy with Srettha Thavisin and will be existentially asking themselves: why there but not here?

Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour is in the UK 7-23 June, then 15-20 August.

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

This article is taken from The Big Issue magazine, which exists to give homeless, long-term unemployed and marginalised people the opportunity to earn an income.

To support our work buy a copy! If you cannot reach your local vendor, you can still click HERE to subscribe to The Big Issue today or give a gift subscription to a friend or family member.