When we lose people we love, we often hold tight to heirlooms. From my grandmother, I have a bracelet of pretend pearls, and a wedding ring of Welsh gold which has now encircled a finger – hers and then mine – for over 75 years. But something else ties me much more strongly to her memory. It is something I cannot hold, touch or even see, but I experience it viscerally in my brain and my body.

It is a song: Super Trouper by ABBA, their melancholy-drizzled disco epic that is almost as well-known in the Western world as a nursery rhyme. But to me it is always this first: Grandma and I together in her kitchen, singing along to the radio, both of us smiling, having fun, feeling like a number one.

Since my book, The Sound of Being Human: How Music Shapes Our Lives came out in hardback last April, I’ve thought a lot about how songs become heirlooms in our lives. Songs are not objects that are passed on, but portals: access points to intense, longing connections to the roots of the personalities of people. When these heirlooms are heard unexpectedly, they can produce deep emotions. When Super Trouper was played during a BBC Radio Wales interview I was doing with Huw Stephens last May, without me expecting it, I was glad that I was off-microphone, as I burst into tears.

Songs produce such powerful reactions within us because our ability to hear and remember songs is built into us from before birth. In my book, I cite one of my favourite studies, from 2013, in which babies in utero were played a specific version of Twinkle Twinkle Little Star, the sounds travelling into their developing ears through their mothers’ growing bellies. It was replayed to them as newborns and then again at four months. Wearing tiny caps of electrodes on their heads, these babies registered heightened electrical activity in their brains when the correct version was played. Songs were becoming heirlooms already, passed on from the womb to the world.

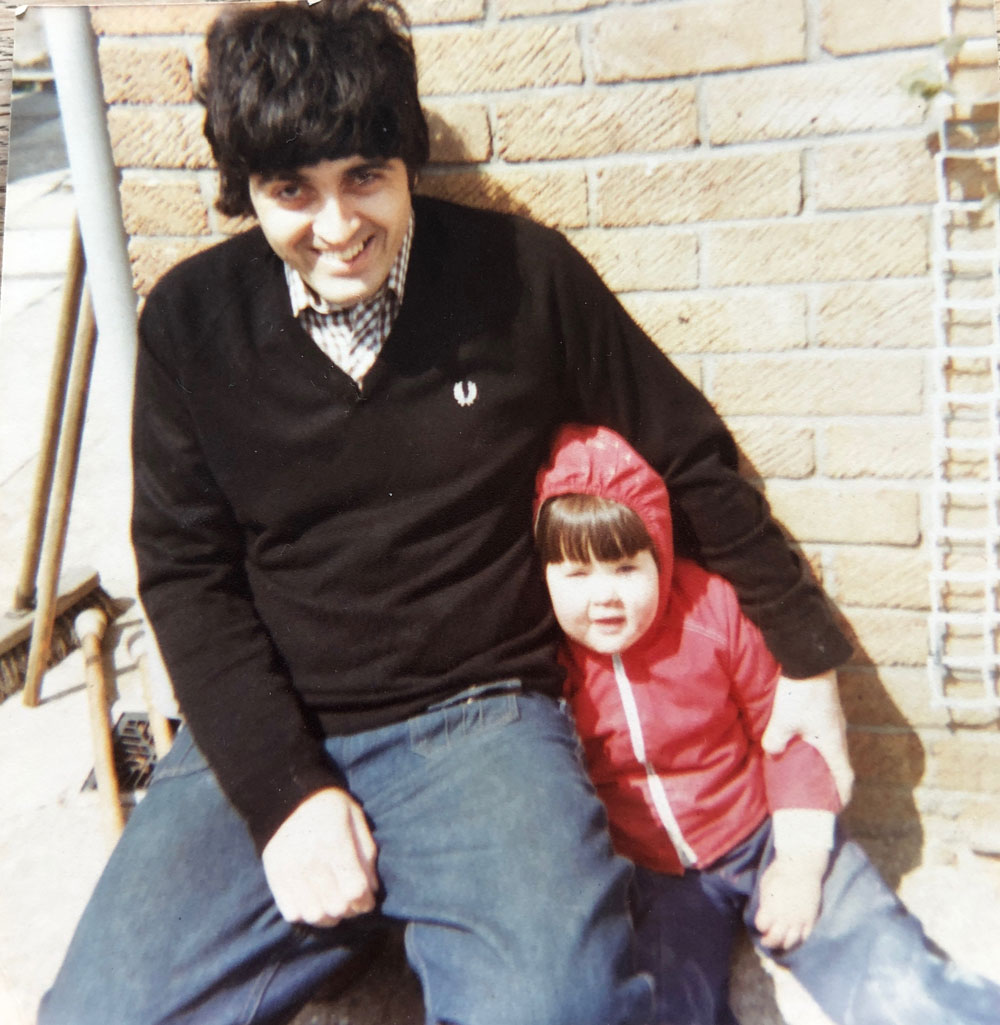

My late father also passed two musical heirlooms to me. They were both released in late 1983: Paul McCartney’s Pipes of Peace and the Flying Pickets’ cover version of Yazoo’s Only You. Before going into hospital for five days for a hip replacement to ease his ankylosing spondylitis, my dad had asked me to find out the new number one. These were the contenders. I never got to tell him that his favourite Beatle won the race. Dad died in the operating theatre two days later. He was 33. I was five.

When I hear Only You today particularly, I am propelled back to the last moment I saw him, the whole scene emerging in full colour. I dug into neuroscience to find out why, and Professor Catherine Loveday of the University of Westminster explained to me how music is a brilliant trigger for specific multi-sensory memories from childhood, including our teenage years, when we cling onto music to help differentiate our identities. The more evolved parts of our brain prompt music-associated memories, so our responses aren’t just animalistic reactions. Music also prompts our unconscious memory system, responsible for actions we do every day but rarely think about like walking. Music is, as my book title celebrates, the sound of being human.