It was the rage that surprised me most about grief. Most of all, I was angry with music. This was far from ideal, given that I was a musicologist: music was what my life was made of. As a teenager, I would have done anything for a life in music. First I’d trained as a classical trombonist, and then I’d taken the academic route, ultimately teaching and researching music in universities.

But after my father died, I couldn’t listen to it. Instead, I sought out podcasts, chatter, television, distraction. Thrillers, explosions.

Days were spent motionless on the sofa disorienting myself within the Netflix labyrinth. It helped me forget who I was and what had happened, just for a while. Like the craft beer I drank.

In truth, though, I’d fallen out of love with music before my dad died. I’d lost touch with music behind a sandstorm haze of academic theories, and the perceived need to like or say the right things to stay in the academic in-crowd.

Get the latest news and insight into how the Big Issue magazine is made by signing up for the Inside Big Issue newsletter

My scattergun grief-rage was looking for objects and directed itself at rule-following and institutions. That summer, I went to a Proms concert at the Royal Albert Hall. There was a Mozart piano concerto, fleeting tones skipping up and down into the vast emptiness above us, and nothing could have seemed more pointless. The grand stupor of the audience, the way they all seemed to be dressed up nicely, obeying the bourgeois norms of the concert hall. What if I stood up? What if I shouted profanities?

It was a long time before I was able to come back to music. Music opens you up in ways you might not yet be ready for. It scrapes away at the strata of your grieving brain, the parts of you that aren’t yet ready to look at what’s happened.

What it took was braving the music my dad played and loved, and realising that anger didn’t need to define me. Realising I was holding on to the ability of certain music – John Coltrane, or Miles Davis, or Isaac Albéniz – to conjure the presence of my dad. I was afraid if I used it up, I’d lose him again.

But I didn’t need to hold on so tight, or to hide my vulnerabilities. What it took was remembering that music, when you get right down to it, is about play.

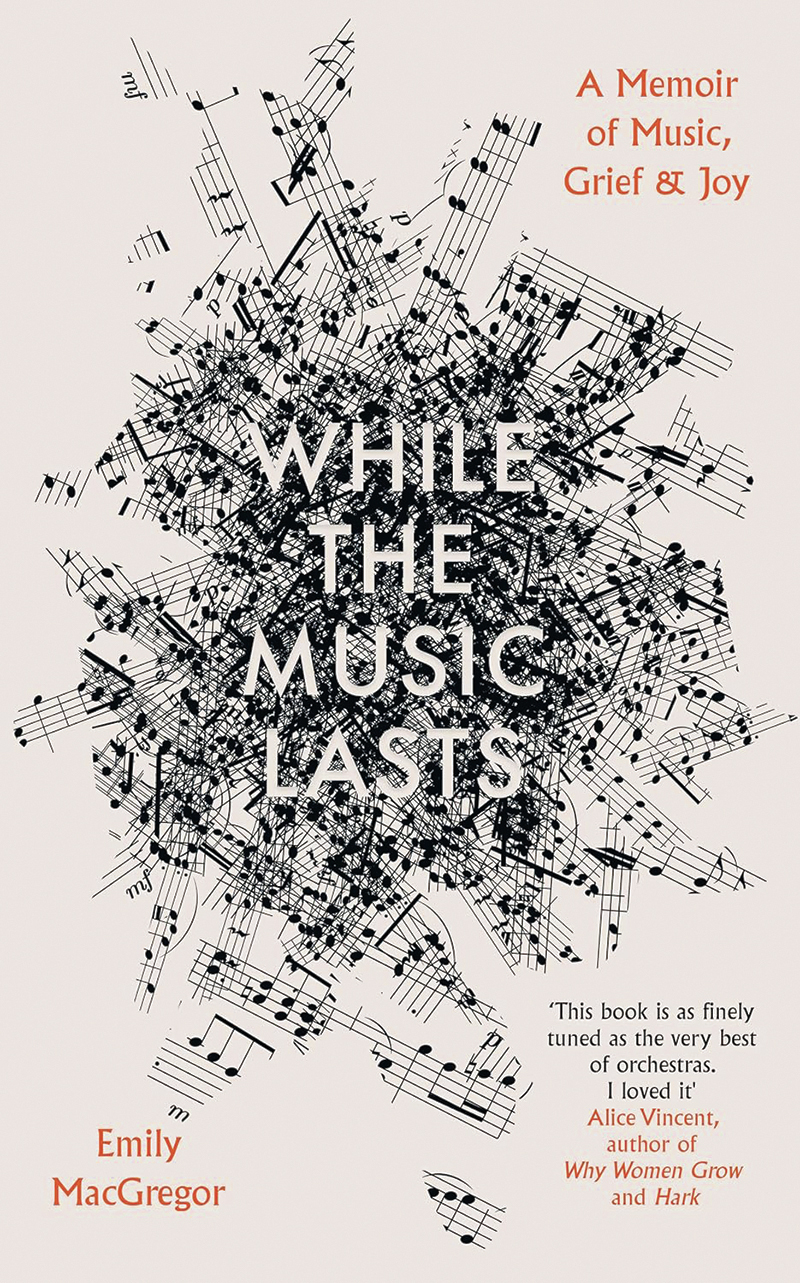

As I explain in my book While the Music Lasts one day, about three years after he died, I made a choice and sat down at the piano. I rifled through a stack of music, and I found a Chopin prelude that looked straightforward. I’ve never been much of a pianist, which meant I’d never staked my identity on being good at the piano, never feared the consequences of getting things wrong. In some ways, it was a fresh start. My puppy accompanied me on her squeaky bear. Squeaky, squeaky, she contributed, as I bashed through a version of the prelude that would have left Chopin totally appalled.

It was fun, remembering the familiar shapes with my hands, the cold, smooth weight of the keys under my fingers, the scent of the paper, the print of the notes. The pure wonder of how music is both rooted in this mechanical action, and somehow also elsewhere, intangible and deeply affecting.

My relationship with music will always be a work in progress. Much as we might want to, we never reach a final cadence in our relationships. Not even when we lose people. I’ve learned that to rekindle how I once felt about music, I needed to let myself forget the rules – and fall. And in this new reality where there is nothing holding me down, I hope one day I will learn to fly.

While the Music Lastsby Emily MacGregor is out now (Duckworth Books, £20). You can buy it from the Big Issue shop on bookshop.org, which helps to support Big Issue and independent bookshops.

Do you have a story to tell or opinions to share about this? Get in touch and tell us more. Big Issue exists to give homeless and marginalised people the opportunity to earn an income. To support our work buy a copy of the magazine or get the app from the App Store or Google Play.