Like most freelance writers, I dabble in the odd spot of ghost writing. Without wishing to open the factory door, this involves preparing drafts that may – or, most likely, may not – be tweaked by the individual you are impersonating, which are then published in their name. It can be strange seeing your words under different authorship, but that is all part of the deal. It is quite another experience to have your work attributed to someone else without your permission, as was the case for many composers.

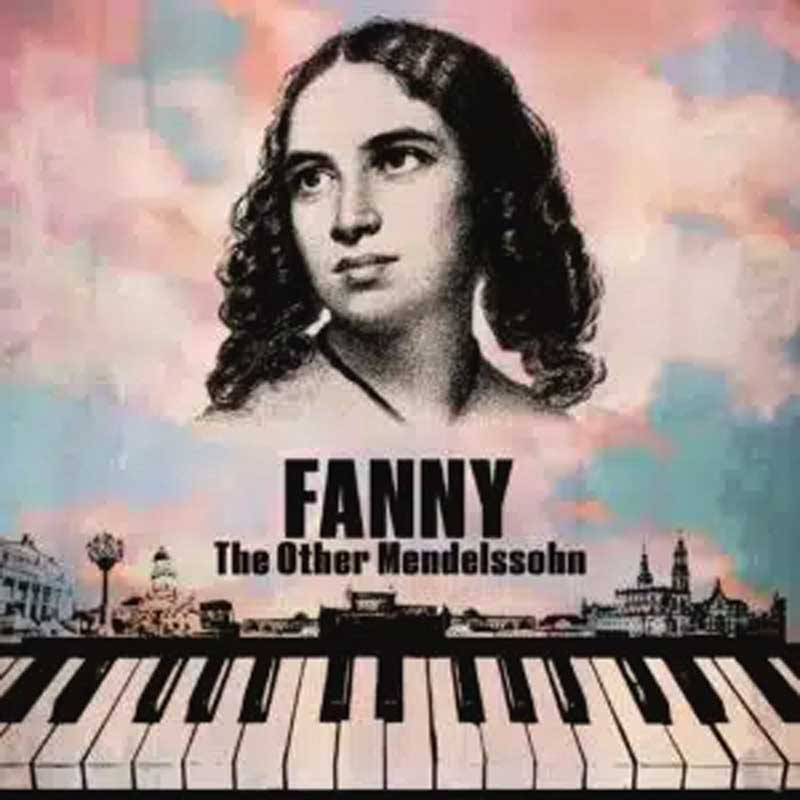

Among the most notable instances of mistaken identity is that of a song admired by Queen Victoria. The score bore the name of one of her favourite composers, Felix Mendelssohn; in fact, the work was created by his sister, Fanny. We’re still discovering that music we assumed to be by Felix was Fanny’s, who was forced to cover up compositional activity due to societal expectations. Much of the lesser-heard Mendelssohn’s manuscripts remain unpublished.

Get the latest news and insight into how the Big Issue magazine is made by signing up for the Inside Big Issue newsletter

Without access to the orchestral forces available to Felix, Fanny focused on pieces for piano and voice. But a new play, recently premiered at The Watermill Theatre in Newbury, imagines what might have happened if she had been able to compose on a larger scale – and perform her own music to Queen Victoria directly.

Fanny, by Calum Finlay, is written in a similar vein to Six, the musical that reclaims the ‘divorced, beheaded, died’ story of Henry VIII’s six wives. As Fanny, Charlie Russell raises her arms towards to audience, conducting an imaginary ensemble. The music she hears is largely in her head, except for the witty interludes created by the play’s music director Yshani Perinpanayagam.

The inclusion of another Mendelssohn sibling, Paul, diffuses the intensity between Felix and Fanny, and their mother Lea, who is given the dubious responsibility of the line: “Music for you must only be an ornament.” (In reality, it was Fanny’s father who said this in a letter to his daughter in 1828.) Finlay packs the script with puns, referencing Fanny’s husband Wilhelm Hensel’s love of wordplay. These include an inevitable – but brilliant – joke about Fanny’s name.