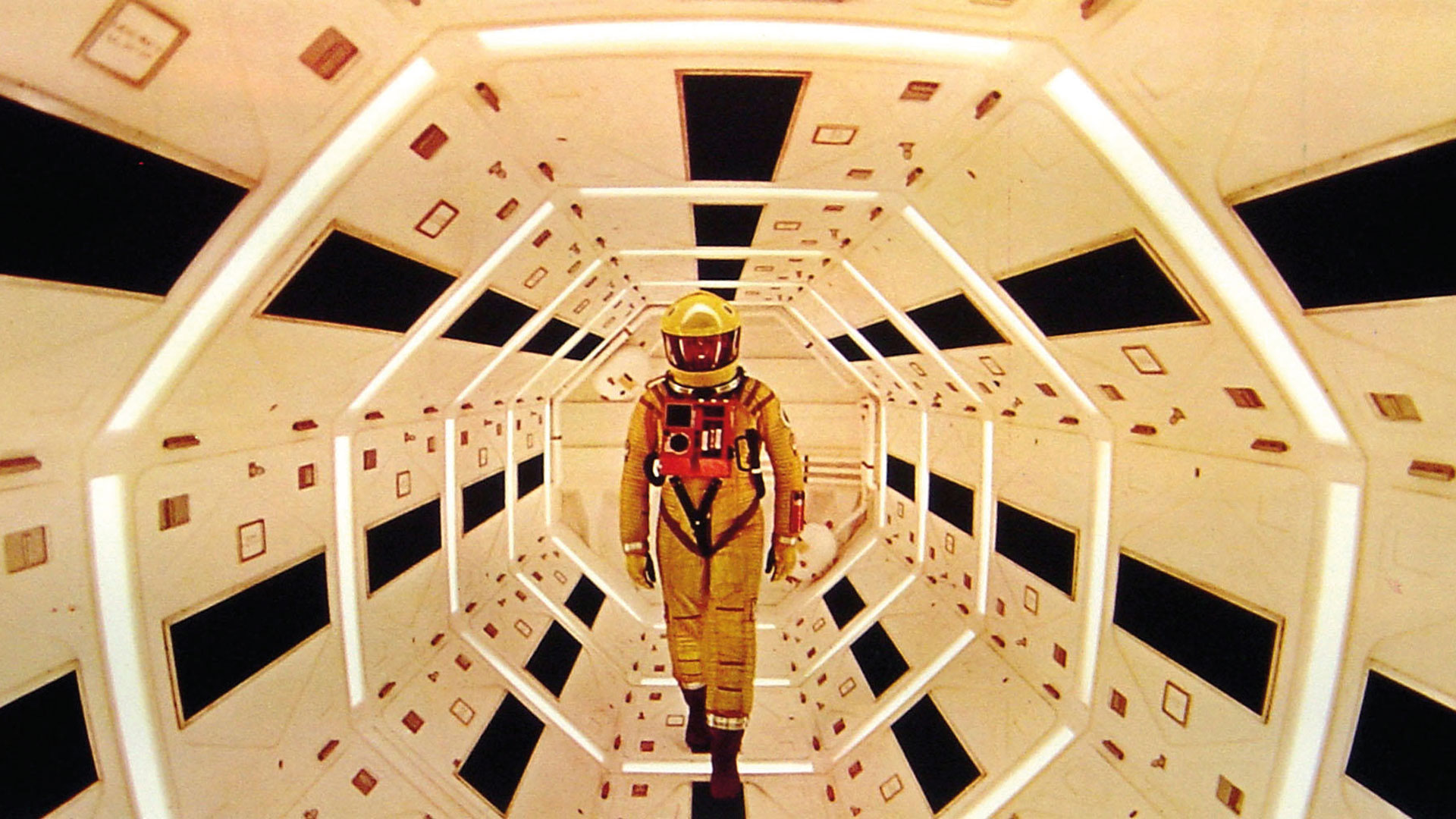

When I first saw 2001: A Space Odyssey, I thought it was long and boring. I was 11 and I was watching it on a small portable black and white television set. Both of these things were a disadvantage. For some dumb reason, even when I had started to appreciate Stanley Kubrick’s other work, I still presumed that it was dull. One day, I shrugged into an IMAX cinema expecting seconds to turn into hours as I watched actors in ape costumes bang each other over the head before an astronaut eventually evolved into an embryonic star child. I am never going to trust that 11-year-old again. 2001 has remained in my top 10 since that day, while the laser gun space westerns I adored as a child slip further and further in their chart positions. Christopher Frayling, a wonderful writer on both the gothic and the spaghetti western, was the presenter of Radio 4’s Archive on 4 about 2001.

For Tom Hanks, the film was a moment when the scales from his eyes were lifted, he described it as “the wow moment” of his life, the moment he knew what he wanted to become. It was a film that changed what people believed science fiction could be on screen. It was the most fully realised imagining of a future in space, a long way from Destination Moon, Things to Come and certainly This Island Earth and Robinson Crusoe on Mars.

Frayling described the meeting of minds between director Stanley Kubrick and author Arthur C Clarke as a meeting of pessimism and optimism. Clarke saw a future improved by the technological products of human curiosity, Kubrick saw progress as combining with a possible regress too, hence the addition of the sound of flies swarming and buzzing during the scenes of warring apes evolving to the point of weapon use.

During the climactic hallucinatory scene, someone shrieked “IT’S GOD” and ran to the screen and then straight through it

The film started out as a portrayal of the human journey into space, but Kubrick eventually transformed into an extraterrestrial Homer’s Odyssey. Originally expected to attract technophiliacs, it became a movie so enigmatic and puzzling that it became a must-go destination for hippies and others who sought truth through chemical stimulation and reading Carlos Castaneda’s charlatan books on the nature of reality. Frayling remembered his own first viewing where, at a point of maximum intrigue, a jazz cigarette was passed along the row.

One of the film’s stars, Gary Lockwood, told of a night where, during the climactic hallucinatory scene, someone shrieked “IT’S GOD” and ran to the screen and then straight through it.