I have been trying to catch up on Radio Four’s A Point of View, a 10-minute pause for thought that I find far more effective for my godless mind than Thought for the Day.

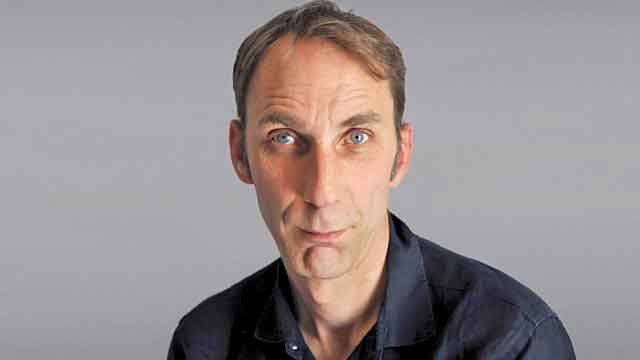

I fear Will Self in the way that I used to fear Jeremy Paxman. Working as the warm-up man for University Challenge many years ago, having been brought in to replace the previous warm-up man whose jokes about nuns on bicycles had not been considered fitting for the usual audience of active librarians, I found my brain jarred mid-sentence by a Paxman look that said, “What is this man and why is he doing this?” It was a moment of jovial contempt. I had a similar experience in a studio with Will Self. He could dash me on the rocks with a sentence. In a recent A Point of View, he talked of rethinking his resignation as a Jew.

The last time the Israeli army invaded Lebanon, he decided he could not identify as a Jew while liberal Jews, who would not condone such actions from any other state, might condone this. Being half-Jewish, he was accustomed to those peculiar moments when, on revealing his cultural background, friends would say his possible Jewishness had never really crossed their minds, before scrutinising his face and commenting that, with close inspection that could see it now, by which they meant, “ah yes, you do have quite a big nose”.

The cause of rescinding his resignation has been his observation of a new form of noxious bigotry, its third form, “the trendy, nouveau anti-Semite”. Those who place the Jews in the background, manipulating the actions of the world, a new conspiracy theory, or a dusting off of an old one in “a world increasingly prey to large-scale popular delusion”.

While scrolling through the multiple missed episodes, I found myself in a truncated 1968. Watching the uncanny realities of American government policy in the last few weeks, where dehumanisation was notched up with toddlers in cages and the rapid actions to normalise it, it was fascinating to listen to Alistair Cooke’s report on the murder of Bobby Kennedy repeated in edited form. He was there when it happened, his thoughts and observations broadcast four days after the events. He spoke of the moment he first observed the fallen Kennedy after the cacophony of shots, “a huddle of clothes and staring out of it the face of Bobby Kennedy like the stone face of a child lying on a cathedral tomb”.

While scrolling through the multiple missed episodes, I found myself in a truncated 1968

He summarised and criticised the sense of collective guilt that ran through the commentaries and opinion pieces in the days that followed: “I have no doubt this experience is a trauma, but I still cannot rise to the general lamentations about a sick society. I for one do not feel like an accessory to a crime, and I reject almost as a frivolous obscenity the sophistry of collective guilt.”