In a world marked by borders and passports, I exist as two people – Peyvand who is British and Parisa who is Iranian. Now, lots of people have dual citizenship, and/or change their names. But both aspects of my official identity, in every sense of the word, are not of my choosing.

I might not have chosen the name Peyvand, but I do like it. It translates to “a connection” or “joining”. But it is an illegal name in Iran, and official names have to be chosen from the official list, and Peyvand ain’t on it.

This isn’t that unusual in Iran – when news in September 2022 broke of the death of a young woman in Iran after being detained for “improper hijab”, sparking the start of the Woman, Life, Freedom movement, supporters for her and her family were keen to also make sure her unofficial (Kurdish) name was spoken: Mahsa Jina Amini.

I am often told how lucky I am to possess two passports. But I must say, I’ve yet to see the personal benefit of this particular pairing. I was born in the UK, and have always lived here, but was not automatically granted citizenship – only discovering paperwork of being born with refugee status when applying for my own passport in my early adulthood. Paperwork confirming I wasn’t in employment when I would have still been in nappies, and seeing my naturalisation certificate at primary school age.

- Iranian ‘gangster’ regime must change, says refugee pop star Shab

- ‘I criticise Israel because I love it, not because I hate it’

- Leila Farzad: I didn’t see people that looked like me on TV growing up

My dad was a refugee who left Iran in 1979, but became British too. I didn’t realise I joined him on this bureaucratic journey despite being born years after his arrival.

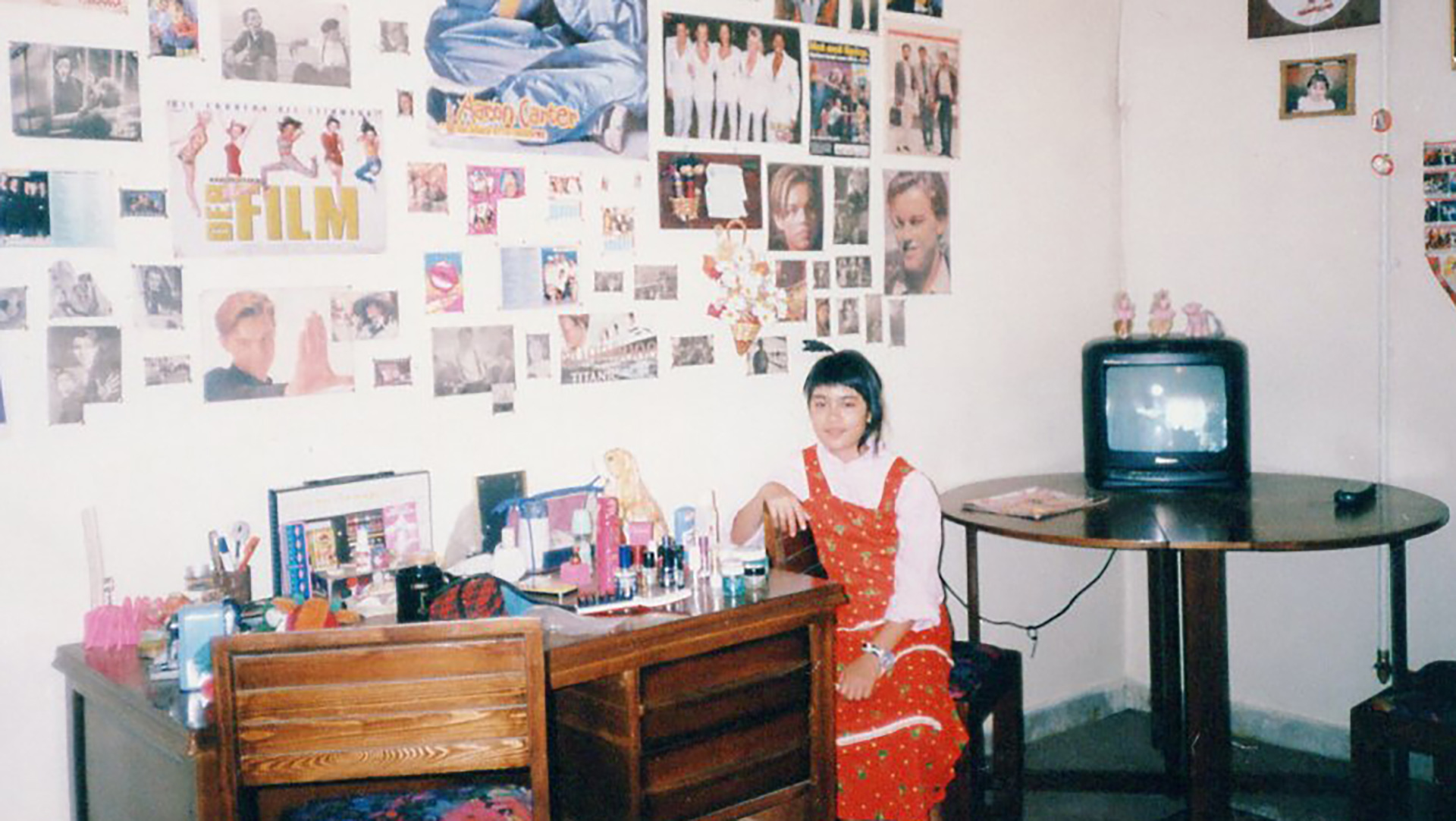

My journey began when I was 10, during a trip to Iran with my father to meet that side of the family. What I thought would be an adventure-packed summer holiday to brag about to my classmates turned into a transformative experience. One that left me politically aware but feeling utterly alone back home in East London. This part of my identity is more than an amalgamation of cultural experiences. It is a testament to the complexities of nationality, identity, and the power they hold over our lives.