It may only be the result of the Earth’s orientation to the sun but the passing seasons are worth celebrating. It’s a big part of what binds us all together in this country, says Cox. “I could say – no, I’m a rationalist and this is nonsense. All that’s happening is that we’re talking about the orientation of the Earth with respect to the sun. Why should we celebrate that?” he admits. “But I just think that’s missing what it means to be human.”

We’re going to do an experiment, in true Cox tradition, to find out if, indeed, I am allergic to the Christmas trees

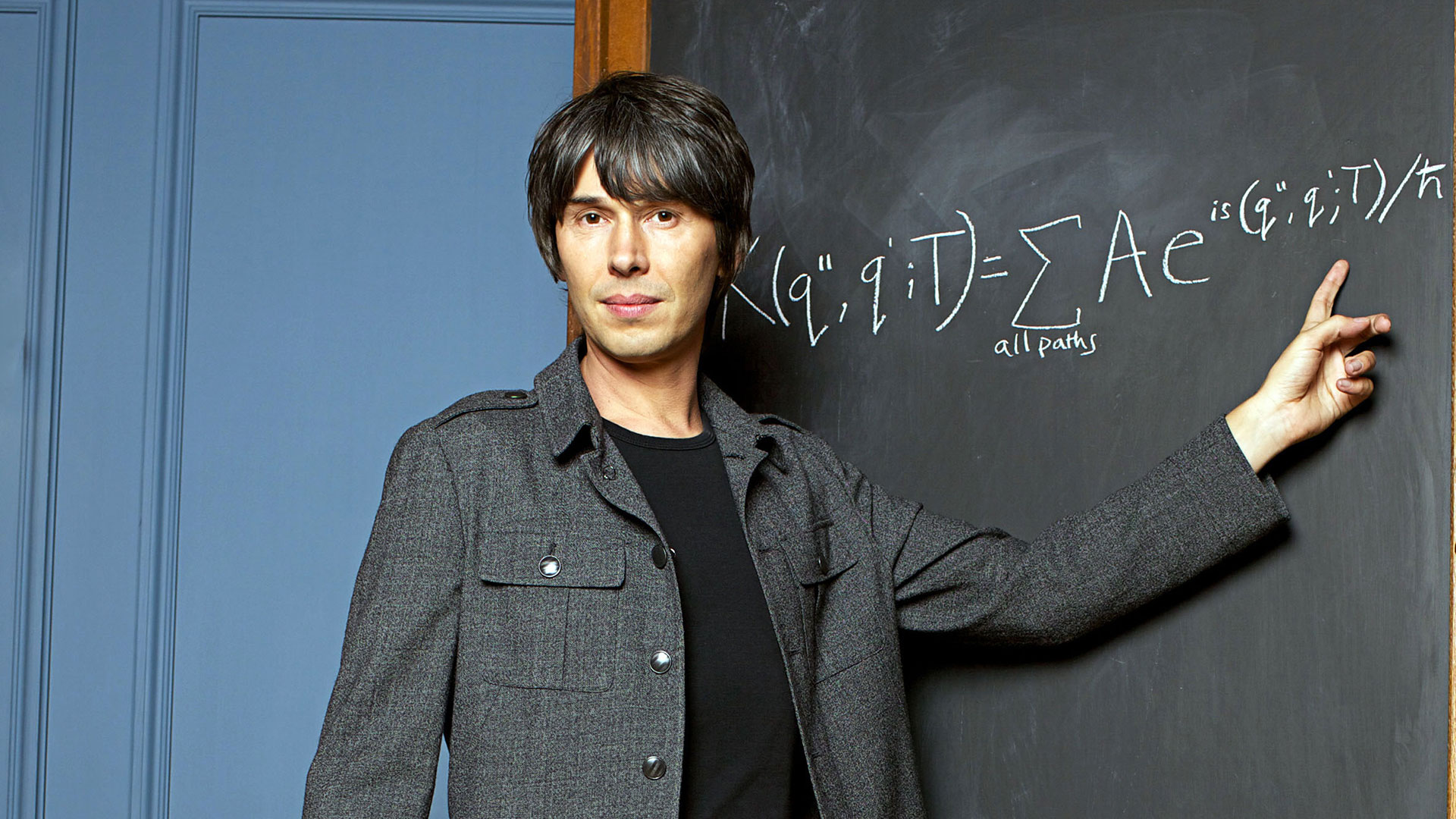

Our humanity, and its value, has been very much on Cox’s mind this year. His latest set of documentaries for the BBC saw him step away from physics for a change and take on biology and anthropology. Following in the footsteps of Jacob Bronowski’s 1970s series The Ascent of Man (commissioned by David Attenborough as controller of BBC Two), Cox’s Human Universe examines the value of human endeavour.

Placing us in the context of what may well be a Milky Way bereft of other intelligent civilisations, it continues Cox’s ongoing agitation for more value to be placed on science and the acquisition of knowledge. But Human Universe also asks what this knowledge will mean for us. “It’s allowed me to think about big questions, philosophical questions, if you like. How should we react if we find out that the universe is in fact eternal? Does that change our view of ourselves? It raises more questions than it answers.”

In letting Cox spread his wings beyond physics, Human Universe further cements his role as the successor to the great David Attenborough. His notoriously giant boyish smile is well on the way to being the face of science on UK television.

How should we react if we find out that the universe is in fact eternal?

The two men are also now friends. “One of the great pleasures of getting to know David over the last few years is that he is just as impressive as one would think,” Cox says. “He invented the science documentary. The thing that I do – these one-hour documentaries where you go places and you talk about ideas and film places that people haven’t seen – he invented that. He’s the instigator of science on television.”

Just as Attenborough has faced various tea cup-sized storms in recent years – remember Polar Bear-gate? – Cox’s love letter to human civilisation hasn’t been without its own controversy. The Guardian ran a piece by controversial palaeontologist Henry Gee calling it “fatally flawed”, while the Daily Mail compared Cox to a bright 13-year-old: “Amusing at first but before long you want to snap at him, ‘Oh do grow up, Brian!’”

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty

This might rock a less wry observer but in Cox it brings out the other side to his public persona. Complementing that puppy-dog enthusiasm is a perfectly honed line in smiling agitation. “It’s a naïve article, full of straw men. It’s basically showing off,” he says of Gee’s piece, while the Mail is merely an irritation, “like you’ve got athlete’s foot”.

As the preceding paragraph shows, Cox’s barbed putdowns of people who refuse to “engage their brains” are a gift to hacks – and to his 1.5 million Twitter fans. But he’s not daft enough to think that arguments on Twitter are going to generate much light. “It’s not worth it,” he admits. “I try really hard to answer people who ask really nice questions on Twitter. And say thanks when people say nice things. I try not to respond to the maniacs. But then occasionally, it’s just sport.”

I try not to respond to the maniacs. But then occasionally, it’s just sport

As we speak, the pro-science wing of Twitter is ablaze with news of the #CometLanding, thanks to the European Space Agency’s personified accounts for the Rosetta probe, which set off in 2004 to catch a meteor that’s moving 40 times faster than a speeding bullet, and the Philae lander that it released onto the hurtling surface of the icy rock, more than 300 million miles away from Earth.

The pair’s separation and the ensuing drama, in which the probe bounced and landed in an imperfect position, thus losing its access to solar power and having to shut down early but not before sending “rich data” to Earth, has been told as though through two backpacking buddies.

Their chat, and the mission itself, has Cox riveted. “It’s scientifically an absolute goldmine,” he enthuses. “Comets are pristine material from the formation of the solar system. There are huge questions about their role in the origin and development of life on Earth. Also, in terms of space exploration, it’s a very high risk, very, very difficult mission. That in itself is quite wonderful.”

For Cox, the Rosetta mission is the perfect example of what human civilisation can achieve. And a salutary lesson, for those who keep slashing research funding, about how much scientists could do with just a bit more cash. “Basically, the comet landing has cost every European citizen a third of the admission ticket to go and see Interstellar,” he points out. “It bothers me because we could do so much more.”

Advertising helps fund Big Issue’s mission to end poverty