In a so-called post-truth age documentaries have never been more important, as film-makers coax out new ways to inform and educate as well as entertain. And they have never been more popular.

Take Making a Murderer, the utterly compelling, adrenalised, immersive true crime story that became the TV phenomenon of 2016. It utilised all the long-form storytelling skills of the current golden age of drama, ending with as many questions for us as viewers as for the law enforcement officers of Manitowoc County and Wisconsin’s judiciary system. Why were we watching – were we complicit in a form of misery porn or active in a project shining a light on failings in the US justice system? These questions are picked up in new Netflix doc Casting JonBenet, which looks to repeat Making a Murderer’s success, before that show’s second season airs later this year.

New technology enables cameras to get where they never could before, which doesn’t only help David Attenborough in the natural history sphere, but enabled Exodus on BBC2 to tell real-life refugee stories, filmed on mobile phones from Syria right across Europe. Their next project is Breadline, where they aim to help people who rely on foodbanks to record their own stories.

I grew up watching Hollywood films and there was not one single film where I could see my story

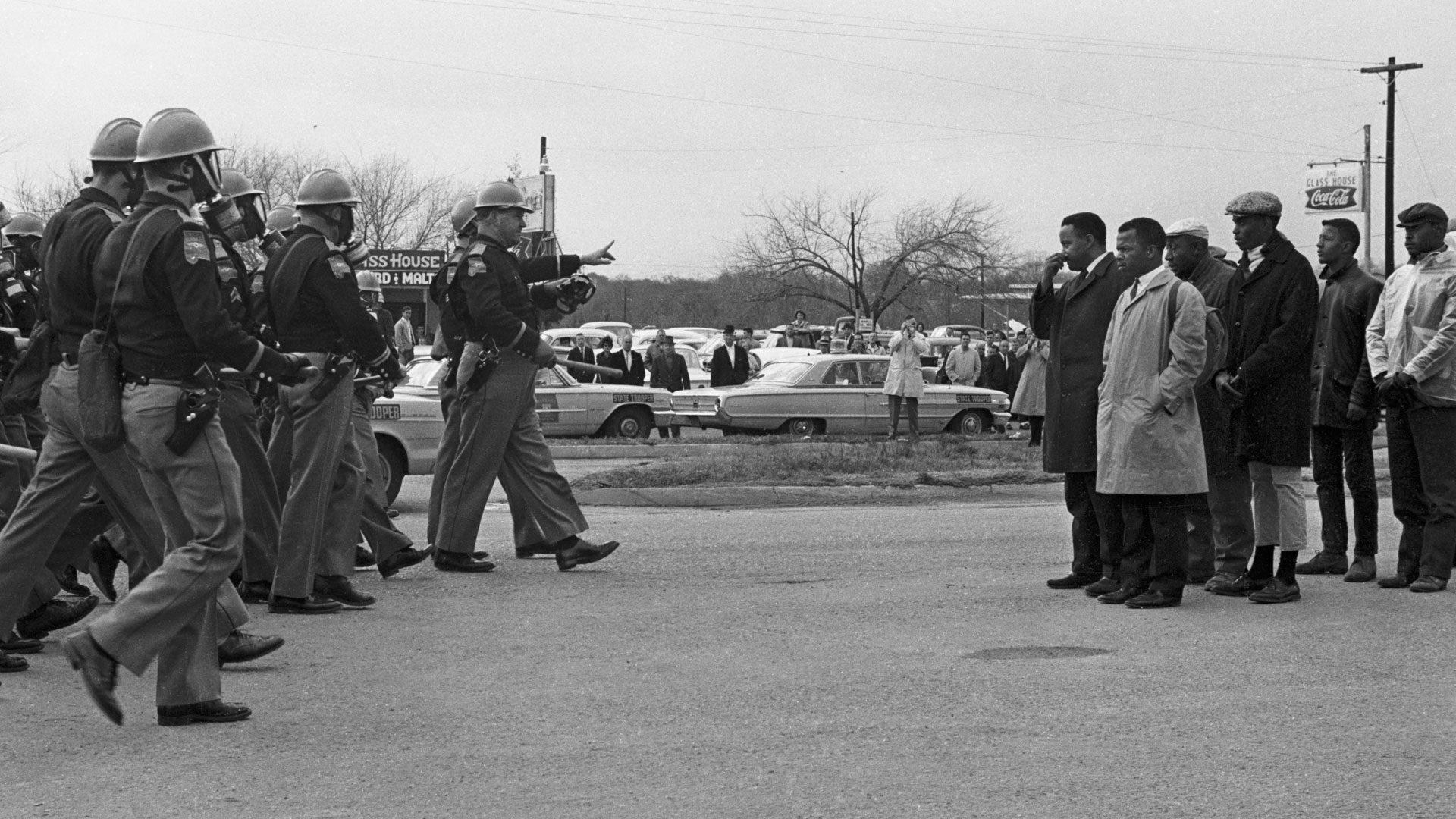

While hard-hitting political and activist documentaries have long had a strong history at the Oscars, Michael Moore’s crossover into the mainstream seemed like an anomaly. Now, factual films are big box office. OJ: Made in America won this year’s award, with its stunning portrait of the rise, murder trial and fall of a sporting hero through the lens of race relations in LA. Also nominated was Raoul Peck’s uncompromising I Am Not Your Negro (pictured above), using the words and works of playwright and essayist James Baldwin to present uncomfortable truths about race in the US.

Casting JonBenet: Are we in a post-true crime TV era?

“I grew up watching Hollywood films and there was not one single film where I could see my story,” says Peck. “And when I was a young man, there were not many writers you could read and think: this is my story, this is my narrative. Baldwin did it not only from the point of view of the black man, or the black gay man, he did it from a very humanistic point of view.